As I write this, I’m stealing glances at a burly-bodied, scraggly-bearded man wearing a black leather cap with a gold cross pinned in front. I first turned to him to find where an annoying scraping sound was coming from: he was grinding his teeth, moving his jaw around like a cow chewing its cud. There is a small pile of tapes at his side. He’s listening to one now on this old pewter-colored cassette player. It’s hard to write as he flips the pages of his newspaper; they’re crackling like snapping flags. He must have felt my eyes on him: he just stood up to leave, but not before balling up one of the newspaper pages and throwing it–over the heads of some perplexed student–into a wastebasket. He missed. I feel like checking what page he ripped out. And I can’t help feeling that I’m in the middle of a Leni Zumas story.

As I write this, I’m stealing glances at a burly-bodied, scraggly-bearded man wearing a black leather cap with a gold cross pinned in front. I first turned to him to find where an annoying scraping sound was coming from: he was grinding his teeth, moving his jaw around like a cow chewing its cud. There is a small pile of tapes at his side. He’s listening to one now on this old pewter-colored cassette player. It’s hard to write as he flips the pages of his newspaper; they’re crackling like snapping flags. He must have felt my eyes on him: he just stood up to leave, but not before balling up one of the newspaper pages and throwing it–over the heads of some perplexed student–into a wastebasket. He missed. I feel like checking what page he ripped out. And I can’t help feeling that I’m in the middle of a Leni Zumas story.

In one of the four letters contained in About Writing (Wesleyan UP), Samuel Delany describes contrasting narrative styles or streams, “writing that is more efficiently ornamented than the norm,” like that of Joyce, Proust, or Woolf, and “writing that is more efficiently stripped down than the norm,” like that of “Stein, Hemingway, Beckett, or Carver.”  He marks yet another stream as the “experimental work” of “a Ron Silliman, a Lyn Hejinian, a Christian Bok, or a John Keene.” Farewell Navigator (Open City), Leni Zumas’s 2008 collection of enigmatic short stories, flows somewhere between the experimental and stripped down streams. The strongest stories, namely “Heart Sockets,” “Farewell Navigator,” “Waste No Time If This Method Fails,” and “Leopard Arms” use slight yet meaningful temporal time shifts, idiosyncratic syntax and grammar, and eccentric narration. And, in stories like “Heart Sockets” and “Leopard Arms,” the author also veers into more speculative and fabulist narrative approaches.

He marks yet another stream as the “experimental work” of “a Ron Silliman, a Lyn Hejinian, a Christian Bok, or a John Keene.” Farewell Navigator (Open City), Leni Zumas’s 2008 collection of enigmatic short stories, flows somewhere between the experimental and stripped down streams. The strongest stories, namely “Heart Sockets,” “Farewell Navigator,” “Waste No Time If This Method Fails,” and “Leopard Arms” use slight yet meaningful temporal time shifts, idiosyncratic syntax and grammar, and eccentric narration. And, in stories like “Heart Sockets” and “Leopard Arms,” the author also veers into more speculative and fabulist narrative approaches.

Most of these stories are compact studies of paralysis, in the tradition of Beckett and Ionesco. These ciphers don’t so much act or react, but are usually quietly or loudly inert. Insignificance, ennui, insensitivity, and impotence all figure largely here. Sherwood Anderson could have been describing Zumas’s characters as they, too, are “forever frightened and beset by a ghostly band of doubts.” In “Farewell Navigator,” one character envies a group of blind schoolchildren having teachers “to pull them. Nobody expects them to know where to go.” And in “Leopard Arms”—a story told from the perspective of a gargoyle—a father fears…

of doing nothing they’ll remember him for. Not a single footprint—film, book, record, madcap stunt—to prove he was here. Am I actually here? he sometimes mutters into his hand. Significant fears to face, I would say: but these two do a bang-up job of not. Their evasion strategy is deftly honed.

Such characters are unmoored in an unforgiving world, bereft of hope for renewal or redemption.

Naming and defining are powerful motifs throughout the stories. Zumas’s characters sometimes come to us by their nicknames–Black, Blue, the fish-stick girl, Blotilla, Squinch, and Johnnycake–but more often they are simply pronouns, or even fragments or sketches. There is a seductive element to how these narratives unfold: a slow accretion of details, together with the use of fragmentation, absence, and space, achieves a confluence of associations, connections, and even some kind of understanding. In a world without much explicit exposition, any tiny elaboration of a thought, image, or perspective becomes magnified: the reader is drawn in to fill in the blanks.

Leni Zumas / photo by Anne Hall (from www.lenizumas.com/)

In “Farewell Navigator,” a teen’s physical blindness seems an insurmountable barrier both to maintaining trust and intimacy with his family and to establishing his independence and own sense of identity. And yet it is a psychological, spiritual darkness that proves to be the family’s greatest obstacle. This is a story of creating a life out of darkness–physically yes, but also emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually. His mother has other blind spots: the story explodes when he discovers her brazenly seducing one of his friends.

Language is celebrated and played with throughout the stories. Characters invent words, usually through pun-filled mash-ups, but in “Heart Sockets” and “Leopard Arms,” Zumas develops unusual syntactical strategies to fit these otherwordy, otherworldly tales. A theme that runs across most of the stories is the discovery of new words. For instance, in “Dragons May Be the Way Forward,” while a mother wallows within television’s wasteland, her daughter revels in language. She tests her mother’s comprehension and patience by reading out loud from the dictionary.

In “Farewell Navigator,” the son learns the word “grubble” from a poem in English class. It means groping or feeling around in the dark. And this is just what we find him doing: trying to make sense of his mother’s senselessness and insensitivity, processing his father’s obliviousness, his own impotence, and reaching toward his own future’s light. This new word, grubble, is used in the story’s most radiant passage where, after the son destroys his father’s jars of plum jelly, his father responds by putting his

fingers to my cheeks, grubbling for tears. His eyes are closed but I see on the red-streaked lids, as if they were maps, how much he doesn’t care if my bloody snot glops down on his shirt. I see how he will hold my shoulders hard and fast for as long as it takes me to stop crying and how I can, if I want, stay bandaged in the soft heat of him for hours, leaking brine, tethered by giant arms to the beat under his ribs till night comes and we’re afloat on dark water, shivering together, hearing the cold get brighter and the waves slower, so slow they turn from liquid to ice—hushed meadows of frozen lather—and we are surrounded.

In this story about blindness, color becomes a powerful element. The son names his parents Black and Blue after what he perceives to be their eye colors. His father, oblivious to his wife’s reasons for being interested in her son’s friend’s green eyes, says, “green is the color of the hair on the ground.” And when the son catches his mother in the act, he runs and hits “the light. Yellow pours onto Blue, who is naked except for her underpants.” The way colors enter into this story is very powerful as is the symbolic message encoded in the parents’ names.

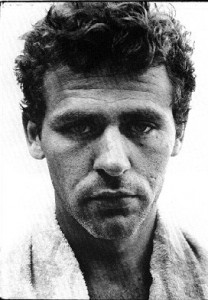

James Agee

Zumas’s love of language and its myriad shadings are explicitly explored in “Dragons May Be the Way Forward.” Besides reading aloud from the dictionary, the narrator luxuriates in James Agee’s writing. “I was stretched on a towel in the backyard, fourteen and no friends, when I first read Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. When the page said, ‘And the spiders spread ghosts of suns between branches,’ a nerve I’d never felt before throbbed between my legs.” Despairing at her tapioca pudding eating and trash television watching mother’s impotence, she cries out to her love: “James Agee, would you please write her into the ground. Tell about the wet earth clumping down on her coffin. Describe her bone-box with your best, your most precise exaggerations.”

In About Writing, Delany also writes about how language delights, startles, inspires. First, he describes a friend turning to a sentence in Joyce’s Ulysses. “Listen to this,” his friend says:

“On his wise shoulders through the checkerwork of leaves the sun flung spangles, dancing coins.” Now I love this sentence. But why is it better to write that than, say, “Sunlight fell on him through the leaves?” Or even to omit it altogether and get on with the story, our day in Dublin?

Delany, in his inimitable style, answers his own question by offering several possible reasons, including this one:

The vividness comes from a kind of surprise, the surprise of meeting a series of words that, one by one, at first seem to have nothing to do with the topic—striding under a tree on a June day—but words that, at a certain point, astonish us with their economy, accuracy, and playful vitality. Again, some of it will work on one reader, whereas others will only find it affected.

Reading Farewell Navigator, we find many instances of this “economy, accuracy, and playful vitality.” In “Dragons May Be the Way Forward,” the daughter looks at her mother, “Folds of skin accordion at her neck,” and despairs that “James Agee could have described her better—would have done justice to my mother, her loggishness, her ghouliness, her secret gentleness…” But what a wonderful image she herself has created to describe her mother’s sagging, withered flesh. And then, bemoaning her own “not-bad shade of blue eyes,” she thinks that Agee would “have piled adjectives upon this blue, lavished it with taut slippery words until it was unrecognizable as a color and had become—a feeling.”  This reminds me again of Anderson in Winesburg, Ohio: writing about a difficult thing, he despairs that his descriptions are not enough, that his technique is faulty. He writes, that what he wrote “is crudely stated. It needs the poet there.” But we have one in Zumas–one by way of Hemingway, Lorrie Moore, and Amy Hempel, with detours through industrial blight, tours of strip malls and stripper bars, layovers in drug-addled adolescence, and twenty-, thirty-, and forty-something unplanned obsolescence.

This reminds me again of Anderson in Winesburg, Ohio: writing about a difficult thing, he despairs that his descriptions are not enough, that his technique is faulty. He writes, that what he wrote “is crudely stated. It needs the poet there.” But we have one in Zumas–one by way of Hemingway, Lorrie Moore, and Amy Hempel, with detours through industrial blight, tours of strip malls and stripper bars, layovers in drug-addled adolescence, and twenty-, thirty-, and forty-something unplanned obsolescence.

While the daughter in “Dragons May Be the Way Forward” plays games with strange words like “moxa,” “umbelliferous,” “flocculence,” and also making up the occasional word, other characters play with imagined etymologies, homonyms, textural associations, and mash-ups. More wordplay can be found in “Waste No Time If This Method Fails.” There’s a funny moment when an overanxious medical student questions one of the hospital inmates about

how he likes it here.

He says, Where—in this cage? and the medical student says, So the hospital feels like a cage to you?

He says. It isn’t a simile. Points at the window: barred. The other window: barred.

He senses the medical student’s disappointment, so he throws him a little bone of crazy. Hearts of oak, he cries, did you go down alive into the homes of death?

When Zumas hints at where these stories might be set, what rings through my head is Neil Young singing, “Everybody seems to wonder what it’s like down here. I gotta get away from this day-to-day running around. Everybody knows this is nowhere.”

In “Thieves and Mapmakers,” Zumas writes about the “Town”:

Although it looked clean on the surface, it was like a river that’s quit running, whose water languishes on the rocks, collecting germs. Because nothing in the Town ever changed shape, hidden viruses were allowed to grow. The rooms of my house stank of sameness…It wasn’t city, it wasn’t country, it was a way station of gray streets and brown storefronts and paralyzed faces.

She describes a similar place in “The Everything Hater”: “a town so tiny we were able to count its stoplights on two hands. This town is small but not quaint or friendly.”

As we bid farewell to the navigator, let us greet this new, compelling voice. I look forward to reading more of Zumas’s incisive prose, especially the more speculative elements of her work. In particular, I’d be interested to see the alternate/parallel/post-apocalyptic worlds of “Heart Sockets” and “Leopard Arms” developed further, perhaps even into novel-length narratives.

Further Reading

Leni Zumas (photo from Open City's website)

– Shopping for a copy of Farewell Navigator? Order from your local indie bookseller.

– Read Zumas’s story “Dragons May Be the Way Forward” on Open City‘s website; you can also read “The Everything Hater” at Five Chapters; “Leopard Arms” at Harp & Altar; “Heart Sockets” at Quarterly West; and “Handfasting” in The Journal.

– On the author’s website, read more fiction by Zumas: “To Greenland,” “An Account of My Death in the Mountains,” and “Diligent Blows.”

– To whet your appetite, here’s a sampling of striking images from Farewell Navigator:

From the title story:

“He hurts himself, sure—blood in ribbons on the cutting board, ropy splashes on the ramekins…”

“I want to answer but my mouth refuses. It makes a little fist on my face.”

From “The Everything Hater”:

“Mom’s face was a punched-out cake.”

“We walk in the glittery cold to the center of town, where ribbons festoon the street lamps and plowed snow hardens on the curbs.”

From “Heart Sockets”:

“His face blown perfect like blue glass animals that cost a thousand dollars to make…”

“I have a talented mind for matching one feeling to another. A caught scarf on the bus seatback, for instance, is the hand on your neck of someone who knows you but when you turn around, nobody’s there.”

“I am leaking heavy onto my shirt, two sopping moons, the mild night a cold sleeve between wet skin and milk-drenched cotton.”

From “Thieves and Mapmakers”:

“Yet he possessed a quality more attractive—to me—than handsomeness: it was his sheer haggardness, the battered-ship’s hull look he wore, as if a lifetime of senseless routines had etched gulleys in his cheeks.”

“All four boys, I noticed, were twitching constantly, glancing around with fretful eyes. Their agitation made me feel closer to them. Their translucent skin, the dried sputum at the corners of their mouths, and the way their shrunken muscles hung as if ready to come off the bone meant they were nothing like the normal people I’d grown up with.”

“Her hair, a dimpled egg, was studded with tiny black bristles.”

“When the sun was up and burning and the guests had cleared away, we settled down on the carpets of the parlor. I dreamed of the Town, of its odors: the first cold day in fall, when all the lingering frowses of heat have left the air and the newly emptied chill is flecked with wood smoke, soft and bitter, the smell of anticipation; and springtime—bright, forgiving air with the hint of unannounced visitors, impending journeys. Of course no visitors ever showed and no journeys were ever taken and the smell would soon retreat, replaced by a dingy warmth. This was why the Town disappointed me so badly: it could never deliver on the promise of its scents.”

From “Waste No Time if This Method Fails”:

“He likes to watch salt dry in bronchial patterns.”

“…but she blinked in a way that reminded him of ocean arachnids who live so many fathoms down their eyes have not reason to grow.”