Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

Today, we’re publishing a double feature: two essays on Lucia Berlin. Jennifer Solheim examines Berlin’s work through the lens of gender, persistence, the history of violence against women, and how we recognize (or don’t) the female experience. This essay was first published on November 15, 2018, and appears below.

Joshua Bodwell also examines what we overlook—in this case, the importance of independent presses like Black Sparrow, which was Berlin’s original publisher. You can read his essay “What We Talk About When We Talk About What We Miss,” which was first published on December 17, 2018.

I: Knowing Women Writers

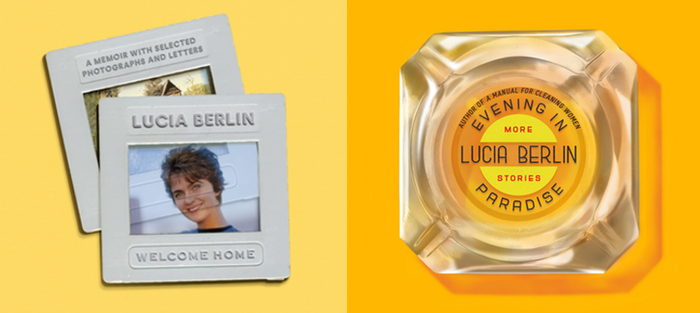

One evening this past August, I kissed my six-year-old daughter goodnight and sat down on the couch to the sound of summer locusts outside the window. A perfect, drowsy reading night. I opened an advance copy of Lucia Berlin’s Welcome Home, a volume that collects her unfinished memoir with photos and selected letters. The book begins with her earliest memories in Juneau, Alaska:

My crib was in the bedroom, where it was either very dark or very bright all the time, [my mother] told me, without further explaining the long and short lengths of the seasons. The first word I spoke was light.

I sat up on the couch, set down the book, and walked into my daughter’s room. I knelt by her bed and whispered, “Sweetie! I’m reading this really amazing writer named Lucia Berlin who you’ll read when you’re older, but guess what? Her first word was the same as yours. Light!”

Bad idea: it took my daughter another hour to settle down to sleep following my intrusion, and there went my perfect reading night. But I couldn’t contain my excitement, and I wanted her to know. I love Lucia Berlin—like, love her—in ways that feel personal and deep. It’s her writing I love, of course. Not Berlin herself. She died long before I knew who she was, and long before most readers of the acclaimed posthumous collection A Manual for Cleaning Women (2015) knew who she was either, despite the fact that she’d published eight books prior to her passing a decade earlier. It’s now a part of Berlin’s mythology: who was this remarkable writer in our midst, and why didn’t we know about her while she lived?

Now writing about the urgency I felt to tell my daughter that she and Berlin share their first spoken word, I wonder: what is the narrative about Berlin—and about my daughter—that I’m trying to convey? What is it about the desire to know as much as possible about writers whose stories relate darkness that no one would choose to face?

Now writing about the urgency I felt to tell my daughter that she and Berlin share their first spoken word, I wonder: what is the narrative about Berlin—and about my daughter—that I’m trying to convey? What is it about the desire to know as much as possible about writers whose stories relate darkness that no one would choose to face?

I know I’m not alone in my fervor for Lucia Berlin, who died in relative obscurity on her sixty-eighth birthday in 2004. But more broadly, there has been a gendered confluence of interest in fiction writers’ backgrounds and biographies over the past few years. A public ardor branded #ferrantefever followed the publication of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan Quartet, and soon thereafter the published volume of interviews, letters, and journal notes, Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey. Part of the fascination with Ferrante—another blisteringly great writer, who, like Berlin, I read only recently yet feel I’ve been waiting to read my entire life—arises from her decision to write under a pseudonym in order to protect her identity. Her fiction drew from personal experience and history, and in order to protect both herself and those close to her she felt an imperative to use a pen name.

A sensationalist male journalist attempted to out Ferrante’s true identity months before Frantumaglia was published; I was disappointed to see The New York Review of Books complicit in this unnecessary outing by publishing the translated exposé. Would NYRB have contributed to a similar intrusion of J.D. Salinger’s or Thomas Pynchon’s asserted desires for privacy? For now, happily, Ferrante continues to be known by her pseudonym only, and while the fervor of excitement for the HBO adaption of the Neopolitan Quartet hasn’t diminished, the fever over the identity reveal has, at least for now, calmed.

II: Women’s Voices, Writers’ Lives

As the hearings on Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court attested, America struggles with the idea that women should control much of anything, in particular their bodies, and by extension, their careers—because to have control over one’s career and income means control over one’s body. I’m not alone in my understanding that the anti-abortion movement is primarily fueled by the attempt to regulate and discipline women’s bodies to conform to a reactionary ideal that women should be in the home, raising children, dependent on the men in their lives. As the Women’s Liberation movement took hold, rhetoric around abortion developed that simultaneously asserts that abortion is killing a child and remains silent on the social repercussions of the lack of support for childcare and women’s and children’s healthcare.

Thus is the atmosphere in which it seems de rigueur to ask women writers about their partners, marriages, and parenting as a matter of routine. In the Paris Review essay “What Does Your Husband Think of Your Novel?” Jamie Quatro describes her initial surprise when an all-male reading group asked her what her husband thought of her book Fire Sermon. “I can’t remember what came out of my mouth,” she writes,

Probably the laugh and the “he’s my first reader and he’s always been a hundred percent supportive” line I would grow accustomed to trotting out in the following months, when the same question surfaced again and again—from strangers after readings, from acquaintances in my town. What I do remember is what was happening inside my brain: What does my husband’s opinion of my book have to do with anything?

And: If I were a male fiction writer, writing about illicit sex, would you ask what my wife thought about my work?

Meanwhile, Lauren Groff’s response to an interview question from the Harvard Gazette about how she maintains her tremendous output as the mother of two children went viral on literary social media: “I understand that this is a question of vital importance to many people, particularly to other mothers who are artists trying to get their work done, and know that I feel for everyone in the struggle. But until I see a male writer asked this question, I’m going to respectfully decline to answer it.” Implicit in Groff’s response is a mandate for men’s accountability; if we asked such questions of male writers with children, we might begin to understand the level of commitment and sacrifice required by their partners and others in their lives, and in so doing, provide models for partners and others of women writers with children. To ask it only of women implies and accepts women’s disproportionate duty in parenting time and energy.

Yet, as a divorced mother, I still want to know how Groff does it. And I want to know how Lucia Berlin did it, too. The letters from the 1950s and 60s included in Welcome Home, when Berlin’s children were small, suggest a writing life in stolen moments—the typewriter in the corner of a kitchen, stories eked out one at a time as the kids played with other children or rode their tricycles in circles around a courtyard. Berlin never mentions anyone—whether one of her husbands, a family member, or friend—offering to watch her sons to give her writing time.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux published Welcome Home alongside a new collection of Berlin’s short stories, Evening in Paradise, on the same day as the midterm elections last week. A knowing wink from the publisher to the politics that these books contain? Perhaps. The American fervor over both Ferrante’s and Berlin’s works and lives was already underway before the 2016 US presidential election, helping build up a good head of feminist literary steam, energy we needed and still need. Then, in the fall of 2017, the #metoo movement got underway, which led in the subsequent months to another kind of fervor for learning the backgrounds of writers. Both Junot Díaz and Sheman Alexie—two of America’s most lauded male minority literary voices—were publicly accused of sexual harassment and assault. In the ensuing months, both have retreated from the public eye.

So perhaps publishing these two new collections of Berlin’s work on Election Day 2018 is a nod to the reverence for her in the literary community and beyond. There are good reasons for this reverence, and to celebrate her work as foregrounding the representation of women’s experience.

It’s high time—and crucial to moving forward as a society—that abuses of gender and socio-economic privilege are brought to light. But if we didn’t have a sexual predator as our president, when would these accusations have been leveled? Within this important movement, how should we reconcile the fact that it started, in part, as an expression of righteous indignation—leveled at those with far less power than the president? The sexual predator is still the head of the executive branch, and he has seated a judge to the Supreme Court with the help of a compliant Congress, even after said judge demonstrated a frightening absence of judicial temperament—partisan, partial, quick to anger, among other things—in response to credible testimony that he sexually assaulted a girl while in high school.

It’s high time—and crucial to moving forward as a society—that abuses of gender and socio-economic privilege are brought to light. But if we didn’t have a sexual predator as our president, when would these accusations have been leveled? Within this important movement, how should we reconcile the fact that it started, in part, as an expression of righteous indignation—leveled at those with far less power than the president? The sexual predator is still the head of the executive branch, and he has seated a judge to the Supreme Court with the help of a compliant Congress, even after said judge demonstrated a frightening absence of judicial temperament—partisan, partial, quick to anger, among other things—in response to credible testimony that he sexually assaulted a girl while in high school.

None of this is meant to imply a silver lining to our current political situation. But these are questions I find worth examining as I proceed with an essay in which sexual abuse and rape will soon become salient. Our motivations for speaking are too many to contain—our righteous indignation has broken the dam of silence, and in the rush to truth—and it is urgent—I want to be thoughtful in how I approach the following laudatory critique, for as I’ve already written: I love Lucia Berlin.

Consider the fact that our daughters are now growing up in a world where Roe v. Wade is more vulnerable than it’s ever been. Both the current presidency and his Supreme Court appointments speak to the ongoing delegitimization of women’s voices and right to control their lives, their narratives, their bodies. So: yes, I want my daughter to know that she shares her first word with a powerful, brilliant writer. I want her to carry this with her, knowledge as power, or perhaps confirmation of her—and all other female and marginalized people’s—authority to write and speak their truth.

And here is where Berlin’s biography alongside the truths she articulates in her fiction becomes relevant. There are hints of physical and sexual abuse in her unfinished memoir, and her fiction is rife with sexual abuse and rape. That’s another reason I’m so taken with Berlin’s work: she conveys these experiences in a way rarely seen. She not only shows the abuse from the victims’ point of view, but she also writes through the acts of abuse, unblinking and unflinching, with both bright clarity and nuanced character shading. Her work is not only about survival, but an embodiment of that wabi-sabi inspired Leonard Cohen lyric: “there is a crack in everything / that’s how the light gets in.”

The likelihood that Berlin was abused as a child—and lived during a time when such abuses were not acknowledged, much less treated in behavioral healthcare—gives us a possible rationale for her drinking problem. This is her biography as posted on the official website:

Berlin worked brilliantly but sporadically throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and most of the 1980s. By the late ’80s, her four sons were grown and she had overcome a lifelong problem with alcoholism (her accounts of its horrors, its drunk tanks and DTs and occasional hilarity, occupy a particular corner of her work). Thereafter she remained productive up to the time of her early death.

There is a clear tension in this statement, which describes both Berlin’s writing and writing life—she “worked brilliantly but sporadically.” This could be accounted for by many things, not the least of which was the fact that she had four sons, a detail we learn from this biography just before we learn that “she had overcome a lifelong problem with alcoholism,” her accounts of which occupy “a particular corner of her work.” Yet the conclusion of this paragraph suggests a causal connection between her drinking and sporadic periods of brilliant work: “Thereafter [referring to both her children becoming adults and overcoming her problem with alcoholism] she remained productive up to the time of her early death.”

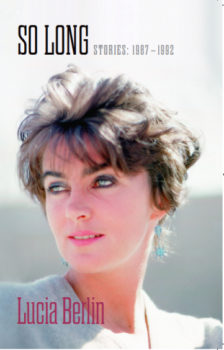

What would Berlin think of the narrative that represents her today? The author photos used to promote her work show the younger, glamorously assembled Lucia of the 1950s, but some of her collections published by Black Sparrow Press later in her life show an older woman with looser hair, settled into a body with more weight on her frame. She’s still beautiful, but it’s a different kind of beauty, and it suggests a different narrative of this writer’s life. By extension, the idea that the younger, more glamorously assembled Berlin is the one that most of her fans now picture is a narrative anachronism. The photos are mostly from the 1950s and early 60s, when she was in her twenties and thirties. But Berlin’s first collection of short stories didn’t appear until 1991, the year she turned fifty-five.

What would Berlin think of the narrative that represents her today? The author photos used to promote her work show the younger, glamorously assembled Lucia of the 1950s, but some of her collections published by Black Sparrow Press later in her life show an older woman with looser hair, settled into a body with more weight on her frame. She’s still beautiful, but it’s a different kind of beauty, and it suggests a different narrative of this writer’s life. By extension, the idea that the younger, more glamorously assembled Berlin is the one that most of her fans now picture is a narrative anachronism. The photos are mostly from the 1950s and early 60s, when she was in her twenties and thirties. But Berlin’s first collection of short stories didn’t appear until 1991, the year she turned fifty-five.

Welcome Home suggests that Berlin would have been in favor of the narrative used to describe her work: in the first pages of the unfinished memoir, she eludes that her output might have been more prodigious were it not for her addiction issues. This passage comes shortly after the revelation that Lucia’s first word was light:

True or not, my remembered Idaho perfumes are more vivid than any flower today. The apple blossoms and hyacinths were literally intoxicating. I’d lie on the grass beneath the lilac tree and breathe until I became giddy. In those days I would also spin around and around until I was so dizzy I couldn’t stand up. Maybe these were early warning signs and lilacs my first addiction.

The subtext here is heartbreaking: it’s a kind of lament for the time she lost to addiction, when she could have been writing.

So as I write this essay, I imagine a portrait of Berlin as she wrote about the perfume of tree blossoms: it is quiet, she is alone, there is morning sunlight bathing the oxygen tank at her side. A writing desk in Boulder, Colorado, where she landed as a beloved creative writing teacher in the 1990s. To co-opt a Berlin line, borrowed in turn for the titles of both Lydia Davis’ introduction to Manual and son Mark Berlin’s foreward to Paradise, Lucia sits and does “the thing.” She’s writing a story.

III: “Andado: A Gothic Romance”

It’s with these thoughts in mind that I move from reading Berlin’s nonfictions and ephemera in Welcome Home to reading Evening in Paradise, a collection of her previously uncompiled short stories. It’s work I realize I’ve been waiting on for years. For when I first encountered A Manual for Cleaning Women, marveling at the stories of gritty life experience, from “Angel’s Laundromat” to “El Tim” (the writing process of which she describes in some of the letters to Edward Dorn included in Welcome Home), I wondered what remained of Berlin’s works: were the stories included in Manual considered her best? Or was there a different organizing principal at work?

Certainly, Manual’s organization helped present Berlin’s work as autofiction—a term that Berlin may or may not have used herself, but which is ably argued for and interpreted by Lydia Davis in her introduction to the book. Autobiographical or not, the themes woven through Manual instantiate some of our most timeworn myths about the life of a writer: alcoholism, love affairs, seediness and glamour, near scrapes with the law and death; and the miraculousness that they still manage to produce a stunning body of work in spite.

In reading this new collection, some of these tropes remain. Yet Evening in Paradise also demonstrates a consistency across Berlin’s published works. It is far from a collection of drafty seconds. Those who loved Manual will be delighted to know that the stories in Paradise are just as masterful.

But what distinguishes the two posthumous story collections is this: in Paradise, the stories from children’s perspectives have multiplied. Where—with a few notable exceptions—adult perspectives and retrospection on abuse, alcoholism, romantic passion, capriciousness, and tenuousness dominate Manual, the stories in Paradise are more frequently from the perspective of children who witness and experience events beyond the limits of their understanding. It’s within the space between these limits and the protagonists’ understanding that the narrative tension emerges between the story and how the story is told.

But what distinguishes the two posthumous story collections is this: in Paradise, the stories from children’s perspectives have multiplied. Where—with a few notable exceptions—adult perspectives and retrospection on abuse, alcoholism, romantic passion, capriciousness, and tenuousness dominate Manual, the stories in Paradise are more frequently from the perspective of children who witness and experience events beyond the limits of their understanding. It’s within the space between these limits and the protagonists’ understanding that the narrative tension emerges between the story and how the story is told.

“Andado: A Gothic Romance,” is a quintessential example. The story is told in close third, from the point of view of fourteen-year-old Laura, whose biography is a variation on Berlin’s teenage years: she is living in the Andes Mountains in Chile, an American girl, “the daughter of a mining engineer, [with] the quality of adaptation common to army brats and children of diplomats. They learn quickly, not just the language or the jargon, but what is done, who is to be known.” Laura will spend the upcoming long weekend at the estate of Andrés Ibañez-Grey, the charming, widowed senator of the mines and a former ambassador to France. Her friends from school, who will be spending the weekend in their typical ways—hairdresser, tennis lessons, worries about dancing cheek-to-cheek in the evening—are impressed by Laura’s plans.

Laura both knows and doesn’t know her vulnerability as a teenage girl; compared to her school friends she seems savvy, but she is also acutely aware of this difference, as well as the fact that her savviness is perception rather than reality. The night before she leaves to visit the estate of Don Andrés, in her childhood bedroom, the maid brings Laura cocoa. She hears the night watchman chanting on the street: “Medianoche y andado. Midnight and ‘walked.’ Andado y sereno… Safe and sound.” The italics and ellipses are from the original text, and for those who don’t speak Spanish we now understand the play on words in the title of the story. To have knowledge is to be safe. And yet.

The next day, as Laura embarks on the train with Don Andrés and his two sons, her father drops her off with no concern about an appropriate chaperone, although the mother of one son’s fiancée (the other son is bound for the priesthood) has a fit about this issue. Don Andrés calms and reassures her. Throughout the entire scene, Laura’s father remains silent on the issue, and easily lets his daughter go.

As the train steams through the countryside, Don Andrés singles Laura out as his companion for the weekend: “When the porter came by, playing a gong for luncheon, Don Andrés said for the others to go ahead. It was as simple as that, the pairing of Don Andrés and Laura for the holiday.”

You can guess where this going, and you hope that whatever this romance holds—for there are elements of it that have potential and indeed feel romantic—that it will be kind to Laura. That’s part of the tension in this story, there’s a queasiness to it. Things are definitely not safe and sound. But it’s breathtaking to watch Berlin at work here, and the ways in which this romance surprises and shocks. Her loving descriptions of the estate and people have the tenuous quality of descriptions of the declining family and decaying estate in Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks, evoking a nineteenth-century sense of romance—the perfect setting for a girlhood crush, following which she should simply be able to turn the page. Neither of the self-absorbed sons are what they seemed to be at first glance. Nor are the servants. Each of these characters bear their own stories in miniature; this is one of the delights of Berlin’s work, where everyone is granted a history, their own fully realized fears and desires, rendered in one stark phrase or delicate description. No one is drawn simply.

Don Andrés makes a steady play for Laura’s affections: “Laura,” he says, when she joins the family in the living room,

“I built [the east wing] from my dreams… from French and Russian novels. The country itself is pure Turgenev… Laura, you will fall in love with my carriages. You can play Becky Sharpe, Emma, Madame Bovary.”

“I don’t know any of them.”

“You will one day. This way, when you do meet them, you’ll put down the book and think of my barouche landau, and of me.”

(Oh. True.)

That parenthetical, which I’ll return to later in this essay, is the one place where an older Laura interjects retrospectively. Otherwise, this story is situated with the fourteen-year-old as she experiences it. Later in the weekend, Don Andrés gets into an argument with his son, who wants to break off his engagement. He angrily orders Laura to come with him for a horse ride. It’s early evening, and they are crossing a rickety bridge over a river, swollen and wild from the afternoon rain. The bridge gives way, and with the horse the two are plunged into the icy water and downstream. When they emerge on a riverbank, Don Andrés rips his own clothes to “bandage gashes in his leg, her arms.” He tells her that the horse will return to the estate and alert the house, but they are miles downstream:

“We’d better start walking, get to the rise above the river. Take your clothes off and ring them out.”

“I’m fine.”

“Don’t be foolish. Wring your clothes.”

They were shuddering; their teeth were chattering.

Aromo stuck to their bare bodies like yellow fur. Laura was cold and afraid. She felt desire and didn’t know what to do, how to do what they were doing. She held his silver head as he kissed her breasts. Fringe of aromo rocking against the sky. An astonishment of pain. “What have I done?” he whispered into her throat. Warm, his breath and body. Sperm glistened, steaming on her legs as she dressed herself.

As they begin limping back toward the house, Laura asks him questions, to which he gives only curt responses. “Why are you angry with me?” she asks. His reply is devastating: “I’m not angry with you, mi vida. I have ruined you and have nearly killed my best horse.” The word “ruined” echoes for Laura through the rest of the story, not unlike the laughter described by Christine Blasey Ford in the Supreme Court hearings preceding Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment (nevermind the subtext of equating girl and horse.) Within the memory of her teenage sexual assault, the laughter of Kavanaugh and his friend is “indelible in the hippocampus.” Lest we hold any delusions about Laura’s hopes and expectations (it would be easier to think that Laura wanted it, because otherwise, indeed, what has Don Andrés done?), here is where Berlin moves us into the first person. This is a narrative shift for which she’s rightly well known; it’s always this stealthy:

He called out for Gabriel. His voice echoed into the vast valley and then there was silence. They walked on.

Ruined? Am I ruined? For such a quick confusing moment? Will everyone know, looking at me?

Laura’s blisters hurt so badly that she took off her boots. He told her not to but she ignored him, pretended not to feel the rocks and twigs beneath her feet.

And if so many women risked being ruined maybe there is something wrong with me, that I scarcely noticed what was going on.

When she needs to stop to urinate, Don Andrés seems angry again. Laura reassures him:

“If you’re angry because you think I’ll tell somebody, you needn’t worry.” There was no one to tell, to ask.

He stopped then and held her to him, kissed her hair, her forehead, her eyelids.

“No. I hadn’t thought of that. I’m trying to think about what I have done. What I can possibly do about it.”

“Please kiss me,” she said. “I’ve never been kissed before.”

He turned away from her but she caught his head and put her mouth on his. His tongue opened her lips then and they kissed until, dizzy, they say down on the hill.

This exemplifies another hallmark of Berlin’s work. She never lets her readers off simply. A reactionary response to this scene might be that Laura must have wanted all of what happened. But it is—it always is—complicated. Remember: she’s never been kissed before. She’s looking for some way to redeem what has happened.

And Laura isn’t finished responding. In the conclusion of “Andado,” she returns to her family. Her mother has taken an overdose of sleeping pills in the midst of her regular drinking, but her father is as usual preoccupied. Her mother is recovering in bed, and Laura goes to see her in the bedroom:

“Have a good time?”

“Yes, I wish you had come. It was beautiful, like a novel.”

“Were the people nice?”

“Real nice. Just family. I rode a thoroughbred.” Helen was looking at a sty on her eyelid in a hand mirror. Laura sat down on the bed across from her mother. Am I in love, Mama? she asked herself. Could I be pregnant? Have I been ruined? Mama, help me.

Romances have been traditionally derided as women’s reading, a harbinger of the decline of civilization. And perhaps that is exactly what they are: they hold the possibility of revelation, experiences that otherwise go unheard, unrecognized. If civilization means maintaining patriarchal institutions and systems in place, it’s stories like these that question and dismantle their value—the very point of court testimony. In the narrative of Blasey Ford’s testimony, how it will change our world is not yet clear. But Berlin’s stories speak urgently about sexual violence, in ways that decades earlier presage how society is starting to discuss this issue today.

IV. Berlin Speaks

In fiction, we can (mostly) evade the scrutiny of the legal system about our own comportment, of men who would have us silenced. In fiction, we can react to assault with defiance, take off our boots against the orders of the patriarch. We can question, feel confused about our experiences, without anyone questioning their veracity. And we can beg Mama for help.

She might not hear. But the reader does.

In parsing the differences in the two posthumous Berlin story collections, perhaps the cracks run even deeper in Paradise because we get the immediate aftermath and confusion for the children from whose perspectives many of these stories are told—but we don’t get the narrative suggestion of resolution through retrospection, because the stories end while the events are still close at hand. And the fact that many of them are in close third, rather than first person, is suggestive of another facet of the challenge of testimony. In the revolutionary feminist essay “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1975), Hélène Cixous writes,

Every woman has known the torment of getting up to speak. Her heart racing, at times entirely lost for words, ground and language slipping away—that’s how daring a feat, how great a transgression it is fora woman to speak—even just open her mouth—in public. A double distress, for even if she transgresses, her words fall almost always upon the deaf male ear, which hears in language only that which speaks in the masculine.

Cixous’ description in the terror of speaking is echoed in Alexandra Petri’s Washington Post essay following Blasey Ford’s testimony and Kavanaugh’s unhinged response. Petri picks up a metaphor in Blasey Ford’s description of how scared she was to come forward: “I was … wondering whether I would just be jumping in front of a train that was headed to where it was headed anyway, and that I would just be personally annihilated.” Petri writes:

The train is very, very urgent. It is moving a man’s career forward. It is very difficult to get the train to stop.

The presumption is that the train will not stop. The presumption is that you will be a scream thrown on the tracks. That it will require a great many of you to be thrown onto the tracks before the train will grind to a halt. It can never be just the one; it must be several at once. Someday we will know the precise conversion. We will tell them: Do not bother unless there are 20 others like you, because the train will continue, and you will be crushed.

Successful narratives, whether in fiction or court testimony, must be carefully cultivated to be compelling and believable. In “Andado,” Berlin doesn’t waver from Laura’s perspective; she lets us see the complexity and confusion of this girl on the verge of womanhood in the throes of a sort-of crush on an older man gone terribly awry, and its confusing aftermath. Laura’s fear and terror only emerges when she’s sitting on her mother’s bed again. But recall the earlier scene when Don Andrés says she would always think of him and his estate when she read the great nineteenth century novels. The narrative reaction?

(Oh. True.)

Perhaps this is why it feels so urgent to know who Berlin was as a person, beyond her writing. Storytelling is a place where truth can be spoken, but during Berlin’s lifetime, for the literary establishment to give her greater recognition would have also meant acknowledging the pervasiveness of sexual violence perpetrated against girls and women every day. The literary establishment could have taken Berlin’s work seriously for its aesthetic value, but her work also forces the reader to consider the social implications of these stories of rape and abuse: how they are told, and by extension how they speak. And as we know, the literary world is just as culpable as any other world: Hollywood, prep schools, the Ivy League, the three branches of government. So this is another possible answer to the question of why Berlin wasn’t recognized in her lifetime. She was, at one point, given an advance for a novel. But much like Tillie Olsen—the story goes—life interfered. Like Berlin’s memoir, the novel went unfinished. What have we lost in the lack of recognition while she was alive?

Perhaps this is why it feels so urgent to know who Berlin was as a person, beyond her writing. Storytelling is a place where truth can be spoken, but during Berlin’s lifetime, for the literary establishment to give her greater recognition would have also meant acknowledging the pervasiveness of sexual violence perpetrated against girls and women every day. The literary establishment could have taken Berlin’s work seriously for its aesthetic value, but her work also forces the reader to consider the social implications of these stories of rape and abuse: how they are told, and by extension how they speak. And as we know, the literary world is just as culpable as any other world: Hollywood, prep schools, the Ivy League, the three branches of government. So this is another possible answer to the question of why Berlin wasn’t recognized in her lifetime. She was, at one point, given an advance for a novel. But much like Tillie Olsen—the story goes—life interfered. Like Berlin’s memoir, the novel went unfinished. What have we lost in the lack of recognition while she was alive?

I’m reminded again of the older Berlin at her writing desk, oxygen tank by her side. Grateful that she continued writing through her work as a single mother, as a hospital aide, a cleaning woman, a high school teacher. Through her problems with drinking. She pursued her art without many accolades in her lifetime, but the mastery of her literary craft speaks for us as girls, women, and writers, indelibly. A sliver of hope in these dark days: the world is starting to catch up to Lucia Berlin.