I recently read a somewhat widely-discussed online takedown of fifteen prominent fiction-writers and poets who, the post’s author proposed, were badly overrated. Specifically, the most overrated in all of American letters. Now, I happened to enjoy this post for what it seemed to be—an enfilade of displeasure opened onto the ranks of contemporary writers who enjoy a larger readership and more critical admiration than do some other underappreciated writers (for instance, the author of the post); but after finishing the piece I scrolled down to have a look at the readers’ comments. Your thinking web-trawler usually avoids the comments thread, as it tends to be depressing on a number of fronts. But as I waded through a few hundred or so of the more recent entries in this unmoderated debate, feeling increasingly agitated and dismayed, I was once again reminded how easy it is in such a forum to dismiss a rival opinion without substantively addressing its merits or faults.

Which is to suggest that if you seek out perspectives on Rick Moody—who did not make this author’s list of unworthies but over the years has certainly had some disparagement hurled his way—perhaps with the intent to make an educated decision about purchasing his new seven-hundred-plus-page epic tome, you’ll likely encounter the usual pastiche of disfavor: stylistic quibbling, with particular attention to the sentences’ tendency toward multiple-dependent-clause sprawl; broader accusations of general excess— too much unbridled self-license; frustration with the frequent formal gymnastics; distaste for that canon-spanning streak of unseemly, Puritanical guilt—the whole range of critical objection that seems to attend discussions of Rick Moody’s work. Some of this criticism will be thoughtful, thorough, and carefully expressed; much of it will be considerably less so. And it’s almost certain you’ll find someone resorting to that stratagem favored by so many among the anti-Rick set, the ad hominem attack. Because it certainly seems like the real problem some critics have had with Rick Moody’s work is a healthy distaste for the man.1

But why is giving Rick Moody the casual kick to the groin such popular sport? Possibly it has to do with his being such a good target for that go-to mode of contemporary discourse, snark. It’s pretty easy to snark on Rick Moody. In interviews he seems to take himself a bit seriously and isn’t all that hiply self-aware (witness the possibly apocryphal account of him taking part in a panel discussion on contemporary literature with David Foster Wallace circa 2002: on being asked to name the best novels of the past ten years, he graciously cites Infinite Jest… before going on to remark that he supposes if he were feeling particularly generous, he’d have to include Purple America in the group);2 he’s of Anglo-Saxon Protestant Northeastern stock; I don’t know that he was inordinately wealthy growing up, but he wasn’t exactly urban poor; he studied at Columbia and Brown; he’s remarkably prolific (nine books in eighteen years; two of the last three topping five-hundred pages), and never seems to let the stretches of doubt and insecurity that tend to plague other writers keep him down for very long; he’s in a band (Wikipedia describes his occupation as follows: Novelist, short story writer, essayist, composer); he resides, at least part of the time, in that bastion of literary irritants, Brooklyn;3 owes at least part of his career’s triumphant ascent to Ang Lee’s decision to adapt his second novel for film; his given name is Hiram…. And so on.

This personal data is available to any opinion-wrangler inclined toward the dominant rhetorical mode, which some days strikes me as just about 99% of all writers working on the Web, which is of course the easiest place to begin any quest for information or opinion. And there’s a real potency inherent in this ubiquitous snark, this tone ready-made for the new millennium’s premium on instantaneous response—ideally via witty riposte—in our age of perpetual information barrage. Because snark makes it easy to express contempt without having to bother with the more annoyingly substantive issues of justifying your contempt for its particular object. And it’s just a whole lot easier to snark on Rick Moody, or to smirk along with some clever commenter’s effortless dismissal than it is to read one of his better books and articulate a compelling case for what it might be about the books that makes the guy so hard to like.

Because even in his pages he can on occasion be difficult to like. Notwithstanding the triumphal tenor these notes will directly assume, I have paused, a handful of times, on looking up from one of those quintessential bad-Moody paragraphs—the self-congratulation oozing from the tail of some joke that wasn’t all that good, the clusterfuck of fancy synonyms, the overlong by several pages Psalmic invocation of light—to reflect that maybe Dale Peck was right. And even if Moody isn’t the worst writer of his generation,4 he’s certainly high on the list of those most liable to get on their readers’ nerves. Why is this? Some superficial reasons are suggested above. But the more relevant point, I think, is that a tension exists between the occasional hint of self-satisfaction you detect in these lesser passages of his work, the pleasure he seems to take in his prodigious gifts, and the reality that Moody simply hasn’t written a book that delivers on the promise of his better passages, those frequently astonishing exhibitions of raw compositional verve that compel you to revisit the paragraph’s (or sentence’s, as is often the case with Moody, he of the several-page-spanning end-stop-less incantation) start, or at least flag the page or something. Moody can make you smile, make you retrace a passage multiple times to savor its uncanny delight, can even make you cry, at least he has done so to me. So why can’t he be more consistently great?

Because even in his pages he can on occasion be difficult to like. Notwithstanding the triumphal tenor these notes will directly assume, I have paused, a handful of times, on looking up from one of those quintessential bad-Moody paragraphs—the self-congratulation oozing from the tail of some joke that wasn’t all that good, the clusterfuck of fancy synonyms, the overlong by several pages Psalmic invocation of light—to reflect that maybe Dale Peck was right. And even if Moody isn’t the worst writer of his generation,4 he’s certainly high on the list of those most liable to get on their readers’ nerves. Why is this? Some superficial reasons are suggested above. But the more relevant point, I think, is that a tension exists between the occasional hint of self-satisfaction you detect in these lesser passages of his work, the pleasure he seems to take in his prodigious gifts, and the reality that Moody simply hasn’t written a book that delivers on the promise of his better passages, those frequently astonishing exhibitions of raw compositional verve that compel you to revisit the paragraph’s (or sentence’s, as is often the case with Moody, he of the several-page-spanning end-stop-less incantation) start, or at least flag the page or something. Moody can make you smile, make you retrace a passage multiple times to savor its uncanny delight, can even make you cry, at least he has done so to me. So why can’t he be more consistently great?

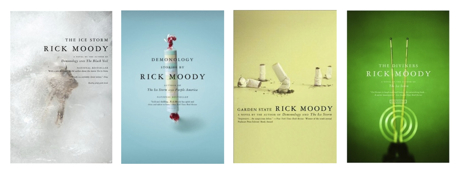

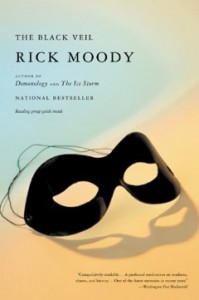

In almost all of his books, Moody is frequently masterful, is transparently possessed of a masterly set of skills, exhibits easy mastery of the formidable range of gifts he’s got at his command; and yet he hasn’t once written a masterpiece. Not one book isn’t flawed in its own frustrating way. The Black Veil’s many bursts of intense, lyrical sorrow were potent enough to punch through the Sebald-lite5 obfuscation of its ruminative sprawl, but it was still a haphazard, erratically written, strange piece of work that I’m not sure ever quite came together in the way Moody seems to have envisioned. The Diviners, which I found heartbreaking at times, plus remarkable for its database-like compendium of fin de siècle American voices jostling for narrative space, was nonetheless grimly unfunny for far-too-long stretches where Rick seemed really hell-bent on making his joke. Demonology’s title piece is one of the ten best short stories I’ve ever read; and the collection opens with a brutal, poignant paean to a strain of suburban lifesickness that a young Rick Moody might have divined as the unappealing alternative to a successful literary career; but the middle of that book is in places a peat bog of narrative murk and uninspired formal fooling-around (although the somewhat notorious “story” that is actually an album catalog is not nearly as off-putting as its description makes it sound). And The Ice Storm’s recurring bodily-discharge gags soil that novel’s stark time-capsule sadness just like the semen in question soils the garter belt that appears far more often than is either necessary or dramatically plausible. And so on. Rick Moody writes good books, in my view, books I certainly don’t regret having read, books that all have their moments, many of them; but not a masterpiece in the bunch.

In almost all of his books, Moody is frequently masterful, is transparently possessed of a masterly set of skills, exhibits easy mastery of the formidable range of gifts he’s got at his command; and yet he hasn’t once written a masterpiece. Not one book isn’t flawed in its own frustrating way. The Black Veil’s many bursts of intense, lyrical sorrow were potent enough to punch through the Sebald-lite5 obfuscation of its ruminative sprawl, but it was still a haphazard, erratically written, strange piece of work that I’m not sure ever quite came together in the way Moody seems to have envisioned. The Diviners, which I found heartbreaking at times, plus remarkable for its database-like compendium of fin de siècle American voices jostling for narrative space, was nonetheless grimly unfunny for far-too-long stretches where Rick seemed really hell-bent on making his joke. Demonology’s title piece is one of the ten best short stories I’ve ever read; and the collection opens with a brutal, poignant paean to a strain of suburban lifesickness that a young Rick Moody might have divined as the unappealing alternative to a successful literary career; but the middle of that book is in places a peat bog of narrative murk and uninspired formal fooling-around (although the somewhat notorious “story” that is actually an album catalog is not nearly as off-putting as its description makes it sound). And The Ice Storm’s recurring bodily-discharge gags soil that novel’s stark time-capsule sadness just like the semen in question soils the garter belt that appears far more often than is either necessary or dramatically plausible. And so on. Rick Moody writes good books, in my view, books I certainly don’t regret having read, books that all have their moments, many of them; but not a masterpiece in the bunch.

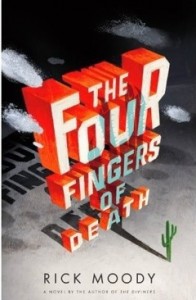

Until now.6 It’s unlikely that this enthusiastic proclamation will secure notoriety for me in the way a certain prior instance of equally-enthused aspersion sent its source careering into modest renown, but in light of how much negative ink has been splashed the Moody canon’s way (granting, obviously, that he’s also done pretty well for himself, and is not exactly in a position to require or maybe even want a paladin at this stage of his career) I think it’s only fair to acknowledge the man in success: The Four Fingers of Death is a triumph. It’s not just Rick Moody’s finest achievement and a total exhibition of his myriad strengths, it’s the best contemporary novel I’ve read in years.7 The final three-hundred pages are a glorious tour de force, just one long, unrelenting roar. And speaking of roars: may I note just how stunned I was to find Moody suddenly, unprecedentedly funny here? So that I was at least nearly roaring, with laughter, mornings on the Nishitetsu train, disturbing and possibly terrifying my native co-passengers on our daily commute; and then at work, where for over a week I contrived to sneak off to our high school’s abandoned “language lab,” where I could read for hours on end and chuckle unselfconsciously without worrying about ruining the other teachers’ days … how did this happen? Did I change? Did he?

I’d read about Moody’s comedic gifts in plenty of back-cover blurbs but found them sort of meagerly accounted for in his actual texts. I was never convinced that Moody quite got how humor worked, some people just don’t—my wife, for instance, has pointed out that although I can appreciate humor, and can even participate in the communal experience of a shared multiphase joke, as a rule I don’t tend to be the initiator of these comic exchanges. There exists an executive gulf between understanding that something is funny and being able to make other people laugh; my wife has kindly put up with this shortcoming in me, but I don’t walk around with blurbs on my back heralding my “comedic gifts.” Moody, while I think possessed of the comic sensibility’s intuitive appreciation for the absurd, never really struck me as having a go-to funny mode, a reliable method of pointing up the sheer senselessness of human suffering that’s at the heart of all humor into writing that could elicit an actual laugh,8 so that you could sense that there was something funny in or maybe underneath the material that found its way onto Moody’s copious pages, but the pages themselves often weren’t all that funny. Only now he’s uproariously on point.

I’d read about Moody’s comedic gifts in plenty of back-cover blurbs but found them sort of meagerly accounted for in his actual texts. I was never convinced that Moody quite got how humor worked, some people just don’t—my wife, for instance, has pointed out that although I can appreciate humor, and can even participate in the communal experience of a shared multiphase joke, as a rule I don’t tend to be the initiator of these comic exchanges. There exists an executive gulf between understanding that something is funny and being able to make other people laugh; my wife has kindly put up with this shortcoming in me, but I don’t walk around with blurbs on my back heralding my “comedic gifts.” Moody, while I think possessed of the comic sensibility’s intuitive appreciation for the absurd, never really struck me as having a go-to funny mode, a reliable method of pointing up the sheer senselessness of human suffering that’s at the heart of all humor into writing that could elicit an actual laugh,8 so that you could sense that there was something funny in or maybe underneath the material that found its way onto Moody’s copious pages, but the pages themselves often weren’t all that funny. Only now he’s uproariously on point.

How did this happen? I suspect he experienced something like liberation in the madcap sensibility and scope of the project itself, but I really can’t say. The book is dedicated to Kurt Vonnegut, and there’s a note of his zany pessimism in Moody’s technofuturistic decay, but the greater debt is to Thomas Pynchon, he of the anarchic romps across continents in ungoverned upheaval, through war-ravaged states, with his bottomless bag of antic pranks . . . except imagine if Thomas Pynchon didn’t sometimes seem a touch sophomoric, if he didn’t once in a while come off as a guy with an enormous vocabulary, unmatched comic gifts, and an encyclopedic comprehension of the shadow-congregations of Power steadfastly guiding modern history toward some apocalyptic end who also really liked cartoons, and then try to picture the byzantine syntax of your prototypal Pynchonian sentence kitted out with a mid-career Don DeLillo’s bladelike precision of phrase, except now further imagine that a novel conjuring a whole world akin to those found in these authors’ large-order dramas of galloping Capital and a geopolitical order held corporate-hostage racing toward annihilation with credit-cards raised, the institutional insights of Gravity’s Rainbow and Mao II, Lot 49 and White Noise, fictions that confront the large, implacable forces that dictate the careening vectors of modern life—governments, corporations, bureaucracies, militaries, crowds—imagine such a novel were to do all of this well, and yet still in the end reveal that its real allegiance was to its individual people, the ones lost in its chaos and decline, that what it cared about most was their longing and suffering, their joy and their pain, that its myriad individual people could speak, that it might wear the mask of a postmodern dystopian epic but that it was really a book about love, which just shouldn’t be possible to tease out from the chaos of its midnight-in-America carnival on-stage, but somehow it is, the book pulses with it, with love, try to picture all this—and then you’ll start to have an idea of the kind of book Moody’s managed to produce.

guiding modern history toward some apocalyptic end who also really liked cartoons, and then try to picture the byzantine syntax of your prototypal Pynchonian sentence kitted out with a mid-career Don DeLillo’s bladelike precision of phrase, except now further imagine that a novel conjuring a whole world akin to those found in these authors’ large-order dramas of galloping Capital and a geopolitical order held corporate-hostage racing toward annihilation with credit-cards raised, the institutional insights of Gravity’s Rainbow and Mao II, Lot 49 and White Noise, fictions that confront the large, implacable forces that dictate the careening vectors of modern life—governments, corporations, bureaucracies, militaries, crowds—imagine such a novel were to do all of this well, and yet still in the end reveal that its real allegiance was to its individual people, the ones lost in its chaos and decline, that what it cared about most was their longing and suffering, their joy and their pain, that its myriad individual people could speak, that it might wear the mask of a postmodern dystopian epic but that it was really a book about love, which just shouldn’t be possible to tease out from the chaos of its midnight-in-America carnival on-stage, but somehow it is, the book pulses with it, with love, try to picture all this—and then you’ll start to have an idea of the kind of book Moody’s managed to produce.

But then, too, it’s still really funny! The high-octane hilarity in these pages in place of previous efforts’ sputtering attempts is a good microcosmic illustration of what’s happening here: for whatever reason—right palette? Right canvas? Right time of his life?—where every previous book seemed to promise more than it could ultimately pay off, in The Four Fingers of Death just about everything works.

Consider the following passage:

And what makes this passage, narrated in what’s traditionally referred to by the type of person who likes to talk about such things (for instance: James Wood) as the “close-third-person,” rather illustrative of how the novel works as a whole, is that in point of fact it is actually not “close-third-person,” though that is the mode Moody employs throughout the second part of the book-within-the-book, from which this excerpt derives; no, technically speaking the narrative mood of the above passage’s poignant, understated, melancholy contemplation would in fact be more accurately described as “close-third-great ape,” as Morton is a chimpanzee who has received a certain stem cell injection that has jolted his previously primate consciousness to self-examining life.And he couldn’t think of what to say about whether there was something he wanted, so he said he wanted Coca-Cola, which was the most recognized and widely circulated American product, and he had read somewhere that the word was the most commonly understood English-language word, after the word okay, and so maybe Coca-Cola, whatever that was, would make him feel okay, and so he sat in the car, with his hand on Noelle’s shoulder, awaiting his Coca-Cola, and she was so good to let him keep his hand there, as he looked out the window at the desperate and slovenly humans coming and going at the not very convenient convenience store, placating their addictions to small things, that Morton wept, because if he tried to mate with Noelle, the hole in him would spill over across the species boundary, because love was the hole as well as the thing that repaired the hole.

A word regarding the notoriously well-embellished language: One critic,9 in expressing his displeasure with Moody’s relentless impulse toward the maximalistic,10 citing a particularly verbose indignation from the latest book, takes Moody to task for his commission of the sort of mistake they teach you how to avoid in “Comp 101.”

Now, having taught a few sections of Comp 101 myself, or writing courses roughly akin, I am willing to concede that this is the sort of thing some of us teach. I have encouraged students, as much as possible, to convey with clarity and concision exactly what they think they want to say, and to pare away excess verbiage wherever they can. But it’s worth bearing in mind what sort of composition we’re talking about in your typical section of “Comp 101”; my instruction tends to stop shy of the 725-page sprawling post-modern opus, because with two or three classes a week and, say, eighteen weeks in a semester, you aren’t likely to have the time. You can teach just about anyone literate—maybe even a consciousness-awakened chimpanzee—how to construct an argument over three-to-five pages. But I’m not sure how much Thomas Pynchon, for example, might have benefited from bi-weekly sessions wherein an adjunct professor offered useful tips on how to rein in those pesky run-on sentences, take it easy on the rumbling metaphors, or, perhaps more broadly, try to focus a little more clearly on his theme.

This “Comp 101” objection struck me as a variety of fruit gone bad, the particularly acetic variety that says “There are rules, and I have to follow the rules: this man is breaking the rules and I can prove it!” Maybe Moody’s apparent quest to pack as much high-grade twenty-first-century English between his book’s covers11 isn’t for everyone, but, even granting that, yes, the occasional sentence does slip up, I for one found the prose a kind of resistless thrill, and actually started worrying, as I moved into the high-five-hundreds, page-wise, about where I’d find substitute sentences to feed the linguistic brain-centers once Death’s were all gone.

You may have heard snippets of data regarding aspects of the book’s structure, as well as hints about its story and place. It is true that our story begins in an unpleasant but likely enough near-future in which the sun sets over the western states of the former global hegemon, now in the late stages of serious economic decline and imperial decay; and it is true that The Four Fingers of Death is actually the title of a novel written within the novel you are reading circa 2011 by a citizen of this blighted future American Southwest, a writer of minimalist fictions with a fatally lung-afflicted wife who’s decided for a number of perhaps not entirely well-established reasons (the rickety preface is by far the novel’s weakest bit, though you’ll just have to trust me when I swear that it does get better, and, more importantly, when looking back on the whole novel you see how the afterword it dovetails with to close the metafictional frame is necessary and effective, or at least makes a certain degree of sense) to try his hand at novelizing the screenplay of an identically titled pulp horror film;13 and then it’s also true that much of the first half of this textual artifact, the embedded Four Fingers of Death, takes place on Mars, and that a certain microbiotic strain encountered on that red planet acts as a prime agent of subsequent narrative motion.

I should also clear up any confusion with respect to the title, i.e., in case you were wondering, it is not an embarrassingly bad metaphorical gesture on Moody’s part, but is a reference to a critical development in the reality of the book-within-the-book, viz., a severed human arm, diseased and with only four fingers to its hand; but I refuse to say a word more about the more or less preposterous—in this word’s most glorious sense—rampaging chimpanzee that in the novel-within-the-novel passes for plot, because to reveal anything is to potentially undermine the impact of any number of ludicrous comic set pieces.

What else? I could talk some more about the clear influence of Pynchon, whom Moody has mentioned reading a lot of in his younger days,14 but has never demonstrated much indebtedness to, the way this novel romps and rollicks across terrain—both thematic and literal—that I don’t think the Moody of ten years ago would have been willing to risk. I could talk about the resonances between outer and inner frame. I could talk about the incredible balancing act he somehow pulls off, sustaining interest for page after page in a novel that isn’t coy about its intentions to go wherever the hell it wants. I could return yet again to the subject of abrupt transition from previous efforts’ often fruitless laugh-hunting into effortless humor, but it wouldn’t be fair to cite only the humor, because, as the above-disparaged Peck rightly pointed out in his unfair polemic, Rick Moody is sad, the feature common to all Rick Moody books is the sadness he pours from himself into them, which is why it’s so erroneous to class him, as I have heard him classed, with “the McSweeney’s set,” or at least with the insouciant tone this has become shorthand for in the contemporary literary scene. Moody has proven he’s much more than that, The Four Fingers of Death is his magnum opus, though I certainly don’t think he’s finished up yet: Moody may make bad jokes, and he may, prior to this book, have routinely overestimated his own abilities, allowed his ambition to launch him into projects he couldn’t quite push all the way through, but he isn’t callow, he isn’t glib, he isn’t quirky, he isn’t geekily overintelligent, and he isn’t even particularly cool; he’s just an earnestly sad guy whose literary career sort of enacts the metaphor that animates his entire previous novel, that of the divining rod, as book after book in the Rick Moody canon finds him relentlessly looking for water.

Further Links and Resources

Endnotes

1. As just one for-instance I seem to recall an occasion when a critic, by way of a mostly-unrelated tangent, remarked that a philosophical topic in something Moody wrote had been thoroughly investigated by far more formidable thinkers than Rick Moody: a rather thorough dismissal, when you think about it, not just of Moody’s writing but of his brain—only which thinkers, in particular, did this critic have in mind? Richard Wagner? William James? Bertrand Russel? Albert Einstein? Jesus Christ? And what were his criteria when comparing these allegedly discrepant levels of cognitive strength? Was his contention for something empirical, like a measurably lower Intelligent Quotient than these eminences on Rick Moody’s part? How did he obtain his information, assuming he had information? What could this brisk dismissal have actually meant? Who knows? But the insidious thing about this method of rhetorical attack is how well it can work. For years I approached Rick Moody (not Rick Moody the man or even strictly the books of the man, but the notion of Moody, Moody the literary idea) with some hesitation or reserve; after all, here was a preeningly ambitious, vainglorious young author operating with the absolute conviction of his first-rate authorial talent who apparently hadn’t been informed that he lacked the prerequisite cognitive firepower, at least this was the perspective I’d somehow managed to absorb from the one glib dismissal without once really stopping to consider what it might—or even could—actually mean.

2.The clip I’d need to watch to verify that this actually happened has apparently been taken down, but I really hope it did.

3.N.b.: I love Brooklyn, and if I can afford it will almost certainly look for an apartment therein whenever I decide to come back from Japan; there are furthermore plenty of fantastic writers and artists of all sorts populating that proud antithesis to Manhattan’s general decline; I’m just noting as plenty of other folks have that it’s also home to a lot of self-satisfaction and artisanal cheese.

4. Generation being a sort of permeable quadrant, though, no? Who, exactly, gets included? Certainly I’ve encountered passages in contemporary novels that were a great deal less successful than many of the most book-chuck-prompting moments in the worst passages of Moody’s worst book (which I actually don’t think I could name; despite their flaws, I do like aspects of all of them).

5. i.e., W. G. Sebald, whom one imagines Moody had been reading a bit of around the time he started working on his “Memoir with Digressions.”

6. Who’s not familiar with the Rick Moody trademark italics? Though it’s worth noting that he’s really toned it down for this outing, and the few instances where he does resort to his old emphatic tricks tend, for the most part, to work.

7. Okay: I read the new Franzen between penning this essay and sitting down to revise it, and while the assessment of Death still holds, I should probably add that Freedom is a comparable behemoth; but who says two books can’t wear the same crown?

8. One possible exception being the early work’s rampant italicization, but that starts to lose its edge once you recognize it’s coming.

9. Sam Sacks of the Wall Street Journal, in review of Moody’s book called “Writing as Recycling”

10. And, to be fair, be warned in advance that precious little in the way of what might potentially be expressed, here, or pretty much anywhere in the Moody oeuvre, but especially here, runs a real risk of going under-expressed; Moody seems insatiable in his need for fresh expression, he’s an enthusiastic user of the so-called “elegant variation” (a term that has been unfairly relegated to the deprecatory side of the barricade—and perhaps the inexperienced writer is well-advised to stick to comfortable lexical territory so as to avoid the boneheaded solecisms of ignorance, but no less a figure than good old Don DeLillo is on-record as saying “there’s always another word”): if a substitutable word exists, he’s out to find and deploy it, so that I do sometimes wonder if he hasn’t either memorized large swathes of Roget’s or else isn’t in a state of perpetual consultation, while drafting.

11. Adorned with, in what is becoming something of a Moody tradition, the hardcover edition’s hideously unappealing cover art; does anyone have an explanation for the huge aesthetic gulf between hardcover and paperback editions? Isn’t the purpose of this graphic representation to allure browsers who might then be persuaded by the printed matter between the covers to go ahead and purchase the book?12)

12. Though, again, I haven’t exactly been getting calls from Moody’s people, asking for marketing tips.

13. The screenplay is actually a remake of a film called The Crawling Hand that winningly exists in both our and Death’s world. I’m told you can watch this gem on Hulu, but Hulu access has been restricted in the Land of the &c.

*Editor’s Note: If you do live in the land of Hulu, and have a spare hour and 28 minutes, watch The Crawling Hand here.

14. Believer, 2006.