I came across Roxane Gay’s 2012 interview with Julianna Baggott in The Rumpus in the fall of 2013. In it, Baggott described her use of not one but two pseudonyms as an author (Bridget Asher and N.E. Bode), and I was curious by the apparent ease with which she shifted genres and readerships. I had just finished her apocalyptic bestseller Pure (Grand Central Publishing, 2012), which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and an ALA Alex Award-winner, and was excited to move onto the next two books in the trilogy: Fuse (2013) and Burn (2014).

In the fall of 2012, I had interviewed Russell Banks on Jeff Davis’s radio show, Word Play, while Banks was in Asheville as a Visiting Writer for Warren Wilson College’s Harwood-Cole Lecture Series. That long-form conversation was later published here on Fiction Writers Review as a two-part interview. I’d always enjoyed reading the long interview, and after doing one with Banks, I was curious what it would be like working with an author whose work was relatively new to me.

As with the Banks interview, I wanted to approach Baggott’s work and her ideas through the lens of working on my own novel: I wanted to ask her questions I was asking myself or wanted the answers to. And I needed a reading project to kick-start the next stage of revision on my book. However, unlike Banks, who I knew personally and had been reading since I was a teen, and whose few books I hadn’t read I could cover fairly quickly, I’d not read any of Baggott’s novels (let alone Asher’s or Bode’s!) with the exception of Pure and Which Brings Me to You (Algonquin Books, 2006), a novel she’d co-authored with Steve Almond. Needless to say, with more than twenty books to Baggott’s credit under one name or another, I had my work cut out for me.

I first wrote Julianna in early December of 2014. I asked her if she would be interested in talking about the span of her writing career (so far) as well as the ways in which she writes across different genres. Julianna wrote back that day with an enthusiastic “Let’s do it!” We jumped into the interview almost immediately. She sent me a box of her books, and I ordered a bunch more. Except for one phone call relatively early in the process, our conversation played out entirely through email. When the interview wound down in late April of this year, I was shocked to see we’d produced over 20,000 words (about seventy pages). It then took about a week for us to boil that down to 15,000 words, which represents a total of about fifty pages. And FWR has generously agreed to host this conversation, which itself will be published in five parts during this week.

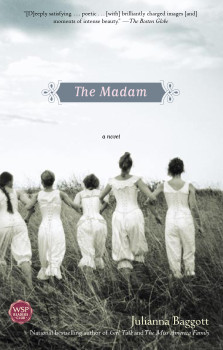

In terms of her biography, Julianna Baggott began publishing short stories when she was twenty-two and sold her first novel while still in her twenties. After receiving her M.F.A. from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, she published her first novel, Girl Talk (Pocket Books, 2001), which was a national bestseller and was quickly followed by The Boston Globe bestseller The Miss America Family (Atria, 2002), and then The Boston Herald Book Club selection, The Madam (Atria, 2003), an historical novel based on the life of her grandmother. Her most recent Julianna Baggott novel is Harriet Wolf’s Seventh Book of Wonders, which came out in August from Little, Brown and Company.

The Bridget Asher novels, published by Bantam, include My Husband’s Sweethearts (2008), The Pretend Wife (2009), and The Provence Cure for the Brokenhearted (2011), as well as All of Us and Everything, which will be released in November.

In addition to the titles mentioned here and those such as the Pure trilogy noted earlier, she has written numerous books for young adult readers under N.E. Bode. Please visit her website for a complete list of titles and more information: http://juliannabaggott.com/

Finally, Baggott also has an acclaimed career as a poet, having published three collections of poetry: This Country of Mothers (2001) and Lizzie Borden in Love (2008), both of which were published by Southern Illinois University Press, as well as Compulsions of Silkworms and Bees (2007), released by LSU Press.

Interview:

Sebastian Matthews: The Madam (Atria, 2003) is very different from anything of yours I’ve read so far. Quite lyrical. Your other books have lyricism shot through them; this one swims and breaths in it.

Julianna Baggott: I talked about The Madam today—in a lecture on creativity and why people stop writing—and how it made me a very prolific writer with a kind of writer’s block. After it, I refused—for a long time—to write literary fiction. Harriet Wolf is—to my mind—my first time really back and it’s not even really… back-back.

What about writing literary fiction gave you writer’s block? Was it the foregrounding of inner life required in the narrator’s voice? The demands on language? The juggling of plot and tone? I ask because I am in a stuck place in my own novel—what feels like a blocked place—and it feels that the demands on the form—genre?—have burned me out.

It wasn’t the craft; it was deeply psychological.

It wasn’t the craft; it was deeply psychological.

For me, writing in a deeply literary way—as in The Madam—or a very commercial and voice-driven way are equal in labor. I know that this runs counter to what people think about literary versus commercial, but once I’m in the world of that novel, I move in similar ways and at similar speeds. I stop cold as often in both kinds of works. The burdens are different, of course, but equally heavy.

But my problem is that my expectations for a literary novel—especially one that’s about my family, my people—aren’t the same as with other kinds of writing. The Madam wasn’t a novel that I expected to hit with readers necessarily, but I did expect to enter into a conversation with other writers; I was ready, for the first time really, to be taken seriously and to see what my colleagues thought of the work.

The review coverage was very spare. And the sales were worse. There was one pre-pub review that took me years to get over. In it were these simple words, “typical kitchen-sink drama.” It felt like a deeply sexist review, especially as it was a pretty foreign kitchen-sink to me—one set in a whore house in coalmine country during the Great Depression; it was a kitchen-sink that took a hell of a lot of research—firsthand accounts of opium addicts from the era and all. I’d have said it didn’t actually have enough kitchen sink. I’ve literally done EMDR [Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing] therapy for that review. It messed me up. Why?

Well, the real problem was that I’d written about women I owed my life to, stories I’d unearthed, voices I gave to those who’d been dismissed in their own eras, only to have them dismissed again. And this wasn’t just my ancestors. My grandmother was still alive; I wrote the novel earlier than I’d wanted because I needed her as a witness. The stories she told me were so brutal that I had to give her a handheld tape recorder to tell them late at night—she was a night owl—and so that I could turn off the recording when it was too much to bear and I needed to walk away.

She actually toured with me; she told Lenny Lopate, “there’s a little prostitute in all of us,” and made Robin Young on NPR’s Here & Now cry—my grandmother’s response to a portion I read was so beautiful.

My grandmother—who was raised in her mother’s house of prostitution—read the novel very slowly, with very poor eyesight. One day, I walked into my mother’s kitchen and she was sitting at the table. She told me she’d finished it. She told me that I’d gotten her mother right. She started crying and because she couldn’t stand up, I got down on my knees so she could hug me. She held me like that for a long time, both of us crying. To be honest, I rewrote her mother in many ways—there were facts that I couldn’t let stand—but I hope I did get to the heart of the woman.

I also killed my grandfather off in the novel and wrote about my guilt in an essay called “Literary Murder.”

This also marked the end of my relationship with my first editor, and I was pretty sure that my career was over. I had a meeting with her while Dave and the kids waited in the publishing house’s lobby. I walked down, pretty sure that I was fired—in that way writers get fired without getting fired. I only remember being dressed to the nines, holding one of my kids, Dave holding the hands of the others, and I was crying and walking them through the busy mid-town throngs.

I just decided I couldn’t hand myself over in that way—not my most ambitious literary self and not the most personal part of myself.

I figured out how to keep writing, how to survive. I’ve become adaptable. And, let me be clear, I can’t actually write without my self—my whole self—and the thrumming of my heart and the silty muck of my subconscious so it was only a trick of my mind that I was somehow less vulnerable. I have lots of ways of tricking myself.

The main point is: I kept writing. I had to.

I found the review you were talking about. And, yeah, you get gut-stabbed there at the end. The “readable, charming earlier novels” remark reminds of Woody Allen’s self-mocking moment in Stardust Memories when the movie critic shouts out, “We liked your earlier, funnier films.” This attempted take down (I call critics “tiny attack dogs”) seems to come out of the reviewer’s reluctance to jump the genre ship. They want you to stay in your box.

I know that art is commerce but the idea that we ask our novelists to be incredibly vulnerable and sensitive (and those drawn to and good at the work often are the most wide open) and then we take what they’ve given and put it through reviews—and THEN ask the novelists/poets…to toughen up…it’s the last part that feels like too much. It’s incredibly bad form for a writer to not take a review—no matter how nasty—in stride. We’re suddenly supposed to be tough and detached…but but but…tough and detached humans don’t usually make good novelists.

The review process is where we lose a lot of writers—the silence and/or the negativity. Even if they seem to take it in stride, it haunts and echoes…I don’t know a way around it.

I totally forgot all other parts of the review—the stay in your box part—though it fits with my feelings of being silenced…

I love what you say about finally writing in your own voice: “I, myself wrote—with my own way with language, independent of my characters.” I wonder if writing about your family and their history—coal mining country in West Virginia—drew you into the realm of the Southern Gothic. That your “own way of language” was informed by your family lineage. Maybe I am reaching here, but it makes sense that the reviewer liked your urbane wit, or however it was put, but couldn’t truck the darker irony and strangeness of Flannery O’Connor terrain.

The actual house of prostitution where my grandmother was raised was near Capital Square in Raleigh, North Carolina. The real South. That terrain felt fully claimed by others much more qualified to claim it. (In short, I thought someone would sound the Yankee alarm.) And so I picked it up and put it in a version of the town my father grew up in—Morgantown, West Virginia. He’d always talked about his coal-dusted childhood with such beauty and a little terror that I was drawn to write that time and place. (I brought the soot with me into Pure.) I identify as a Yankee, but, as a writer, I have to be shoved at least partially into the Southern Gothic camp. The larger-than-life storytellers in my life were all Southern—I’ve likely mentioned that I grew up three blocks from my grandparents, my grandmother who grew up in that house of prostitution and my grandfather, a double amputee from World War II; they lived in a smoke-choked ranch filled with poodles and handguns. I grew up on oyster dressing and okra.

I interviewed Russell Banks a couple of years back, and during our talk we focused in on his novel Lost Memory of Skin. I was comparing the point of view in Rule of the Bone (first-person) to that in Lost Memory (close-third). Here’s what he had to say:

That’s an intimate voice that Lost Memory uses. There is that close third where you get up into the head of the character but you don’t rely on the character’s first-person narrative to tell the story. You use the diction that the character would be familiar with and comfortable with; and to some degree also the intonation and inflection and the syntax that the character would use. But you don’t look out through the character’s eyes in the same way. It’s a fabulous kind of point of view. It empowers the author in a way that allows you to both inhabit the character and also stand outside of the character at the same time.

You write in close-third in The Madam. I’m curious what you remember of that process—if you started writing in first-person, for instance, or began focusing on another character other than Alma. Also, when did you hit upon writing in other points of view? I find it striking, and slightly unsettling, that you allow other characters’ points of view to enter in.

I’m proud of this moment in the novel actually. To me it’s one of the few times I really actually consciously had a kind of form meeting function in point of view. As long as Alma, the mother, holds the family together, the point of view is hers. When the family fractures, the point of view fractures into multiple points of view. In this way, the decisions I made with point of view are supporting plot; the psychology of how it’s told supports the deeper psychology of the novel and its characters. That was the intention, at least, and I don’t actually expect a reader to be aware of it. The unsettling quality, to my mind, would be enough—that fracture getting at the reader in different ways.

And, yes, I tried various points of view yes, including first-person. Banks’ description here is very well put. I wouldn’t say I’m quite as close in third as he’s talking about here, however. I don’t blur as much syntactically as third would have allowed.

My first novel was in first-person. My second in two alternating points of view. And I say that The Madam is the first novel that I, myself, wrote—with my own way with language, independent of my characters.

You’ve mentioned Marquez and Irving as being tutelary figures. I’ve evoked Oates and Auster. Hearing that you’re writing a horror book makes me think of Stephen King—and not just because of the genre. He’s a highly skilled writer, and storyteller, who seems to be able to write any kind of story, in any form. (The memoir section in his book on writing is a knock-out!) Is King an influence? Or is there anyone else who has been a really guiding light for you?

An early review of Pure called it horror, and a short story that was used to create Pure was up for Best American Horror, according to the literary magazine where it had been published. I was stunned by the word. I hadn’t set out to write horror at all. And yet around that time I was working on a project with Steven Schneider, the producer of Paranormal Activity, and around this time we had a meeting with Roy Lee, producer of The Ring. I had my assistant at the time watch the films and tell me about them because I knew I wouldn’t be able to sleep if I saw them—and likely not for a very long time. A few years earlier, I’d decided I was a grown-up and an admirer of King’s short stories, and I really was dying to read his novels. I’d been able to read The Shining and Delores Claiborne out of order, somewhat, just opening the book and reading a scene, but not straight through because I got too scared. I picked up It, and I fell in, truly enjoying the prose, the agility within and between scene, all kinds of beauty. And I believed that, finally, my professional experience as a novelist had made me immune to fear—I was looking at the gears of the narration, right? But then, suddenly, I was terrified. Completely terrified and I shut the book and threw it on the floor.

But my reaction to being called a horror writer was to say, Wait, you haven’t seen me write horror. If I do horror, you’ll know it. It felt like a challenge.

That said, I could barely write the Lizzie Borden poems in my collection Lizzie Borden in Love, and really had to stop doing any research about her at night.

That said, I could barely write the Lizzie Borden poems in my collection Lizzie Borden in Love, and really had to stop doing any research about her at night.

I’ve gotten scared watching Murder She Wrote and playing the board game Clue—why would a professor bludgeon someone to death with a candlestick holder? I saw it really vividly.

Again, though, regardless of the above—and because of it—I’d love to write horror, one day. I don’t think what I’m working on now is going to turn out to be horror at all.

I’ve read and been influenced—as a fiction writer—by a lot of poets. Sharon Olds, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Adelia Prada, James Haugue, Seamus Heaney, Marie Howe, Daisy Fried, David Wojahn, and Terrance Hayes, to name a few. There are some poets—Matthea Harvey, Rachel Zucker, Olena Kalytiak Davis, Andrew Hudgins, Philip Levine, etc.—who inspire me as a poet. Maybe those names blur in influence but I really look to poets a lot—for fiction techniques, epiphany in particular, but also how to stain the reader’s eye and yet tell a succinctly powerful and surprising scene. I’d say your father, for example, falls in the category of influencing me as a fiction writer more than poet.

Looking back at the span of your writing career so far, any regrets? Anything you’d have done differently if you could?

This is the first question that’s sent me staring out my window. I don’t spend time thinking in this way. I’ve had things go wrong; I’ve made a lot of corrections or attempts at corrections in how I operate in the world as a writer; I’m frustrated by certain aspects of myself (some that seem stubborn); but I really work very hard to learn from failures, of various kinds. There are times when I’m completely stumped by the lesson I should learn or the way to take something forward and that’s very frustrating. I watch my male colleagues navigate in a very different way and I envy that except then I see the various ways it fails them. I’ll say this maybe. I recently finished up a workshop on creativity for faculty in various fields. A physicist told me that I was like Chili Davis, the Red Sox hitting coach. That I didn’t care if the group liked me. I took each of them as individuals and tried to make their unique processes better and stronger. I was moved by the comparison, but quickly said, “One thing, I really do want you all to like me.” That said, I also really want each of them to have processes that make their work stronger, because I believe in tending to process—it benefits us as a culture. I would say that my fuck-off and my fuck-it are things that I consciously have to work on.

And I know this is going to sound insane and I don’t expect many people to understand it, but I feel like I’d have had one more kid if I hadn’t taken on academe. We needed academe but in those seven years between my third and fourth kids, I imagine we’d have had one more if it had been possible. That said, bearing children has been hard on me so I’m also thankful for the brood we have.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on something that’s fighting me. I don’t know its structure. I don’t know where the bulk of the story exists—in the past or now or both. And I haven’t ever really had this exact kind of problem before. It was a horror novel, to be honest. And I wrote ninety pages very quickly. Then I realized that I didn’t really understand what I was writing and I didn’t think it was sustainable. (I’ve gotten much deeper into novels—twice at around page 165—before realizing they’re not sustainable so ninety feels almost merciful.) I think I’m figuring it out again. Today is a day without interruption—the first in a long, long time—and I’m hopeful that I’ll find firmer ground. But it’s just day-to-day, right now with this one, which might be a thriller. I can’t tell.

I’ve also handed off my fourth collection of poems, and I’m waiting word from someone I deeply trust. I’m waiting for my colleague to send on her rewrite of my rewrite of the opening chapters of a novel we’ve worked on for a few years. And I’m waiting for a screenwriter I’ve been working with on an adaptation of my upcoming Asher novel. We’re a few drafts in and getting close.

Last question. It’s been fourteen years since your first novel, Girl Talk (Atria, 2001). You’ve written close to twenty novels so far, with two coming out this year. In that interview I did with Russell Banks, he said, “…as I grow older it becomes increasingly difficult for me to recreate in myself that state of not knowing what I am doing.” Can you relate to that sentiment?

Yes. It’s a trick to find ways to take you, the author, out of authority. The genre hopping is one way I do it. But I once had this strange experience. I was asked by this guy if I’d be part of this writing experiment—Quick Muse—two poets get a prompt and have fifteen minutes to write a poem. I had some favor to ask of him so we worked it out. A couple months later, we meet in person at a reading. He tells me Robert Pinsky is the poet I’m going up against. I say, “Funny. The former US Poet Laureate is also named Robert Pinsky.” He tells me it’s THAT Pinsky. Nervous, I say to myself, “Fine. Who’ll ever pay attention to this, anyway?” The morning of the event, I get an email from an old friend wishing me luck. I ask him how he knew. He said he’d read about it in the New York Times. Shite. So I freak. I get all geared up. I’m in my mid-thirties and this is serious for me. The prompt has to do with jazz, which I think is an obvious softball to Pinsky, but I do my best. I email with Pinsky later. His poem is formal—perfectly crafted. He wrote it while watching the Red Sox, distractedly. Dusted the thing off. What I felt, in response, was fear. It was a beautiful poem, and my fear was what happens if it becomes easy. Who would keep doing it? Would I? No.

Yes. It’s a trick to find ways to take you, the author, out of authority. The genre hopping is one way I do it. But I once had this strange experience. I was asked by this guy if I’d be part of this writing experiment—Quick Muse—two poets get a prompt and have fifteen minutes to write a poem. I had some favor to ask of him so we worked it out. A couple months later, we meet in person at a reading. He tells me Robert Pinsky is the poet I’m going up against. I say, “Funny. The former US Poet Laureate is also named Robert Pinsky.” He tells me it’s THAT Pinsky. Nervous, I say to myself, “Fine. Who’ll ever pay attention to this, anyway?” The morning of the event, I get an email from an old friend wishing me luck. I ask him how he knew. He said he’d read about it in the New York Times. Shite. So I freak. I get all geared up. I’m in my mid-thirties and this is serious for me. The prompt has to do with jazz, which I think is an obvious softball to Pinsky, but I do my best. I email with Pinsky later. His poem is formal—perfectly crafted. He wrote it while watching the Red Sox, distractedly. Dusted the thing off. What I felt, in response, was fear. It was a beautiful poem, and my fear was what happens if it becomes easy. Who would keep doing it? Would I? No.

I recently read a clip from Billy Collins in Powers of Two: “After you’ve found your voice, you realize only one person to imitate and that’s yourself.” I thought in my head: And then you can die. Maybe this imitation of Self works for Collins. It would kill me. I have to fool myself, at least, that I’m not just Baggott being Baggott.