Imagine living in a world where others could steal your thoughts, where brain pirating actually exists and your mind is never alone. A world where robots can be adopted to fill the role of a sibling for your lonely only child. A space where your entire universe is dictated and run by a computer-simulated program that could become corrupted at any moment due to a virus or a glitch, thereby causing the world around you to be shut down—leaving you to start your very reality all over again.

In Children of The New World (Picador, 2016), the debut collection of short stories by Alexander Weinstein, such concepts and questions are not only plausible but extremely real. One’s mind can be completely manipulated simply by purchasing memories and uploading them or “beaming” them into the brain. What would your present state of consciousness be if your existence hinged on computer-simulated memories or virtual realities owned and operated by corporations? There is something enticing and almost irresistible about the idea of having access to a surplus of sensory data—complete with feelings of love, loss, war, birth, success, desire, romance. With the click of a button you could be in Tahiti or caught up in a thrilling and new love affair with the most attractive person you have ever seen in your life. Who wouldn’t want to recreate their own image? At this point you may have the power of God. Make yourself as perfect as possible. Then again, as tempting as it seems, the dangers may create a total shutdown of identity, leaving you empty and alone and utterly dependent on an all-seeing eye or at the mercy of hackers who turn your world upside down. Where is the deep end, the point of no return?

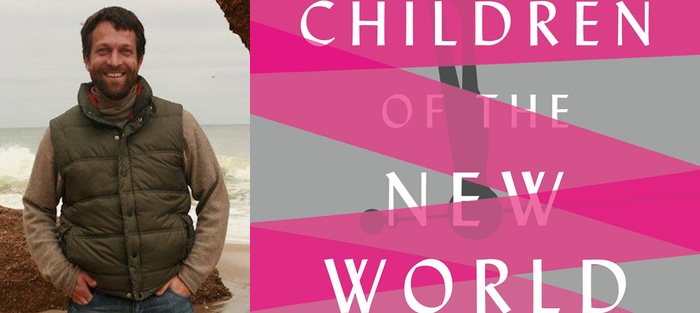

Children of The New World sheds light on what may be a potentially close future and questions whether or not human beings can survive such experiences and existences without completely fading away. Fortunately, I had the opportunity to have a conversation with the author, where he discusses his writing process while working on Children of The New World, his thoughts on philosophy, and his feelings about our ever-changing reality.

Interview:

Nina Buckless: What was the seed or germ for Children of the New World?

Alexander Weinstein: One night, about ten years ago, my computer crashed, taking with it much of my work up until that point. I was pretty devastated, especially because I had an emotional connection to the laptop (it had traveled with me through three states, been with me when I got into an MFA program, etc.) and I began to cry. At that moment, I realized I was emotionally connected to my electronics! Around this time, all my students were getting iPhones. In class they’d talk about how much they “loved” their iPhones. This revealed to me how widespread this emotional connection to technology was becoming, which played into the first story I wrote for the collection. So my laptop became Yang, the robot child who malfunctions in “Saying Goodbye to Yang.”

As the smartphone/Facebook/Instagram/Tinder/Snapchat years have gone marching on, things have increasingly gotten more emotionally strange, so there was a lot of fodder for new stories. I hadn’t set out to write a full collection of technological satire, but the stories just kept coming, so the book came together rather organically.

Yes, the relationship and the emotional dependency to the tool. It is as though the laptop has become a critical element of identity and memory. An emotional attachment to our devices seems nearly natural today.

Eileen Pollack, a former professor of mine at the Helen Zell Writers Program, often talked about the necessity of creating a deep interior world for a character. Sometimes, this can be a struggle for a writer. In Children of The New World, it struck me that your characters have full-bodied inner emotional and psychological lives. How did you approach developing their interiority, their emotions, their pathos?

Thank you—it’s great to hear, since that’s my intention with my characters. I want them to feel full-bodied with inner emotional lives, and most importantly, I want the reader to feel their hearts. I remember hearing a quote from Sherwood Anderson, which went something like: “If I sell out my characters on the page, it’s like selling out humans in real life.” I’m sure it was much more poetic than that, but I remember it being a turning point in my writing/education because I realized I’d been selling out my characters on the page.

Thank you—it’s great to hear, since that’s my intention with my characters. I want them to feel full-bodied with inner emotional lives, and most importantly, I want the reader to feel their hearts. I remember hearing a quote from Sherwood Anderson, which went something like: “If I sell out my characters on the page, it’s like selling out humans in real life.” I’m sure it was much more poetic than that, but I remember it being a turning point in my writing/education because I realized I’d been selling out my characters on the page.

When I first started writing, I used my fiction to either glorify “bad characters” or to ridicule them. The unreliable narrator became my bread and butter, and during my undergraduate years I wrote a series of pieces focusing on horrible characters with corrupt morals. In retrospect, this was odd, because in my personal life, I’ve always been interested in how to make the world a better place, how to help those in need, and how to work to lessen suffering. And yet, in my fiction, I spent pages creating senseless suffering for characters. My characters seemed to notice this too, and so about a dozen years ago they all went on strike. The word had gotten out: I was a condescending, cold-hearted author, and my stories lacked the presence of human love. So my characters abandoned me, and I found myself finally having to make amends with my characters and my narrative choices. What was central to rediscovering my writing was learning how to have empathy for my characters, and to align their deepest hopes and struggles with my own.

This was the key realization for me: to listen to my characters rather than my preconceived notions or judgments about them. Take the father in “Saying Goodbye to Yang.” When I first wrote that story, I tried to make him into a kind of business-minded CEO, wearing a suit, and all that stereotypical junk. Well, I got to page two, and I remember a small voice saying, “No way, Alex, you’re not about to do your old business-man critique again—that’s some real horse shit. This character is like you. He’s a father, he’s struggling to make ends meet, and he loves his family. Now start again.” So I did, and it was the first time I watched a character come alive for me on the page. That story taught me that if I give my characters a piece of what I love and hold dear, then they’re more likely to become human, and in turn there’s a much greater chance I’ll be able to see them more clearly. Similarly, with characters I dislike, I still try to give them something beautiful, or some aspect or quality I admire. This way I can’t sell them out. The biggest danger is that I use my characters as pawns/soldiers to simply advance my plot (in which case I’ve turned them into drones) or I sacrifice their humanity in order to prove whatever moral I’m trying to make (in which case I’m literally using their bodies as a soapbox). In both cases, I become a bit of an asshole, and my stories and characters become flat. So the key is to let go of both the plot and the moral I want to prove. The moment I do that, the story becomes alive, the characters begin to breathe, and I’ve got a much more exciting adventure ahead of me.

In your story “A Brief History of the Failed Revolution,” Krotsky, a critic and philosopher, writes in his essay, The Global Interface as Political Machine:

“If we see consciousness as belonging to an individual, in much the same way that we consider personality, free will, or even the notion of soul as his/her own possession, then we must concede that any technological intrusion, cybernetic or electronic, is a forcible one. As such, the individual should have the right to reject it.”

This struck me as quite fascinating and a key element to the book, because it leads me to consider a deeply thematic question—whether the internet is requiring our collective consciousness to become corporate?

I do think the internet is rewiring our consciousness to become corporate. I’ve been thinking about the way we tend to use social media. We were raised on advertisements, which showed us “perfect lives,” and we’ve started curating our profile pics and Instagram posts as a further extension of this marketing. There are the filtered photos with soft edges, a table in a field somewhere, everyone having a midsummer fest, or a bar photo with the lights just right and the mojito perfectly backlit. We’ve internalized the tricks of advertising, and now we’re hoping our own photos might better capture the dreams those advertisers cultivated as we run a marketing campaign for the product, which is ourselves.

This is even more pronounced in the world of dating apps, where people are literally figuring out how to market their desirability so they might be clicked on. The technology itself teaches people to swipe individuals into the trash if they don’t meet our preferences. And I think this ultimately trains our consciousness to work from a commodity-level intelligence based on corporate gain. What can this person do for me? How can they benefit my life? How do they match up with my preferences?

This is, then, the other kind of sacrifice zone—the psychic/emotional/psychological geographies of our lives. Every time we waste our time checking Facebook feeds for the hundredth time, crushing candy, or hunting for the perfect emoji, we’re ceding our consciousness to technology. Our free time is given up to the click-bait emotions and psychological algorithms of marketing. In short, we’ve allowed our consciousness to be strip-mined. When we find ourselves discussing how Kim Kardashian’s naked ass has “broken the internet,” marketing and pop culture has essentially bought and sold our consciousness.

Later in the same story, it is argued that consciousness is public property. In this way intelligence is seen as some sort of capital. Are we heading in that direction (brain pirating, intelligence as capital) or are we already there, somehow? Is it possible?

On a literal level, I don’t think we’ll see corporations laying claim to the inner functioning of our souls quite yet. If they could figure out how to crack that code, I have no doubt they would. In the story “The Cartographers,” Quimbly ends up working for a company that creates Thought Ads—which are later explained in the story “Excerpts from the World Authorized Dictionary” as a neural marketing probe that clings to spinal-receptors. If advertising firms could figure out how to plant ads within our neural passageways, they’d do it in a heartbeat. Corporate America has no remorse, no morals, and it sells people’s freedom to the highest bidder.

So, the question I wonder about is: if there ever came a day when technology wanted access to our souls, would we put up a fight? I mean, how many of us have read the user agreements of our latest iOS update or Twitter agreement? I haven’t. For all we know, we’ve signed away our rights, our friends’ rights, and our family’s rights—but we shrug our shoulders. So there’s a way in which we’re becoming increasingly open to a violation of our privacy and personal consciousness. Once we start getting into wearable technology like contact lens screens, I think we’ll be all the more prone to shrug off intrusions to our consciousness.

Of course, on a metaphorical level, we’re already there. I’m particularly interested in how the West has co-opted spirituality: the yoga classes with dance mixes and hundred-dollar yoga mats, the DJ ayahuasca ceremonies, the weekend shamanic/electronica festivals. In all of these cases, there’s a desire to make the personal landscape of our inner worlds into profitable enterprises. And there’s a growing interest for these more “consciousness-based” gatherings. In one way this is good, because folks are looking for a deeper connection. But, on the other hand, there’s still the same uncontrolled egos running these ceremonies as one might find amid power-hungry CEOs, and there’s an exploitation of people’s spirituality for profit, power, and sex. It’s what Chogyam Trungpa called spiritual materialism. I think the challenge for us as individuals remains the same: how can we detach from the glitz and glamor of the capital-based model of consciousness to create a more authentic connection?

What is brain pirating?

Ha! You know, I never really thought that one through, but in the context of that story, I see it as hackers being able to take over people’s thoughts. My guess is that when it started (circa 2026) it was probably mostly being done by really shady advertising agencies (a form of insidious viral marketing) but I imagine eventually it would expand into both the private and political sectors, so you could hack someone’s mind to make them fall in love with you, or want to give you money, or affect their emotional states. Governments could pirate your brain to make you support a certain candidate. And then of course there’d be wars over brain pirate terrorism.

It seems that many of the characters in the book are left unfulfilled and lonely because they spend so much time being entertained by simulated realities, beamed false memories, or searching for enlightenment in far off places. In this way I wondered if they have become slaves to their dystopian environment? Have their own personal thoughts been stripped from them? Are these characters chasing their own desires or are they chasing ideas of what their desires should be?

As someone who is deeply interested in Buddhism, these are questions I ask myself every day. What’s actually beneath the desires that I chase after? And how many of my desires are based on projected fantasies manufactured by marketing interests? As I talked about earlier, I do think a great deal of our desires are manufactured, and we see this played out in the ways we use social media.

There’s a great deal of unfulfillment and loneliness in our culture—and this is what the characters in my stories are dealing with. They are chasing the second-level desires that have been manufactured for them. What’s at the heart of the conflict of many of the stories is characters having to face the emptiness of their desires, which often uncovers some lost piece of their hearts. The father in “Migration” remembers that what matters in life isn’t having sex with a barely legal online avatar, but reconnecting with his son. In “Moksha,” Abe learns that even the search for electronic enlightenment is empty when you’re just looking to escape reality. In this way, there’s a Buddhist core at the heart of the collection, one that is always looking at the way our desires (and the second-layer of manufactured desires) lead to greater suffering rather than liberation.

The worlds that your characters inhabit are often holographic or fully computer-simulated realities—so to speak. They have avatars that they either become or interact with, they recreate their environments via computer programs, build family units that are dependent on a computer program and dependent on the corporation who developed the software. They beam memories. Some even live their entire lives indoors. Their entire world can crumble from a virus or a slight programming error. They are often left helpless and incapable of solving the problem, much like people today who have no idea how to fix a broken dishwasher or a transmission—because they do not have the skill level to fix the very same program or computer system that they are dependent on. Or do they have one foot in a holographic world and one foot out of it?

I’d say my characters are one step further into the holographic universe than we are. But maybe I’m just being optimistic. I mean, do you remember telephone numbers anymore? Any numbers I learned before 1999 I recall in an instant—but the moment I started using a cell phone my brain stopped working in that way. I can use GPS to get me to the same place a dozen times and yet never memorize how to drive there. And I have a host of virtual “friends” on social media that I haven’t actually seen for over a decade (for all I know they could be AI programs posting photos of great meals and smoothies). Last month, I even got to try virtual reality. It was amazing, and will, undoubtedly, become our future. So, maybe we’re already living holographic lives as fully as in my stories.

At the same time, we still have farmer’s markets, bicycle rides, gardening, communal farms, dinner parties, book store readings, small presses, bands playing in funky little clubs, and cohousing communities. So I have a great deal of hope for humanity and our ability to come together. And while I’m clearly critical of technology, I’m not anti-technology. We’re going to need technology to help solve some very serious issues, like our need for clean drinking water and solar/wind power. And technology can indeed bring us together. The Women’s March on Washington and the excellent organization of protests (like what we saw at JFK Airport after Trump’s horrendous immigration ban) has been due to the success of social media. Of course, these examples are also dependent on people coming together in real time and creating community.

It’s funny, I was recently joking during a radio interview that I was thinking of starting the Landline Movement. A couple days later, I got an email from a listener, sharing his story of giving up his cell phone and installing a landline. He spoke of the past year of withdrawal, how it had been hard at first, but now things were getting better, and he was reaching out to lend support to my attempt to kick the addiction of my data plan. It was very sweet and also completely dystopian! Who knows, we might find support groups for virtual addiction in our future. We’ll go to meetings in the basements of elementary schools where they’ll teach us how to throw a Frisbee or how to have a water gun fight again.

In my stories, many of my characters missed their opportunity to make space for such human connections—and so they sold their free time to cyberspace. Now they have a much greater hill to climb because they already, literally, sold off all their land (both the physical land and their mental geographies). As for the rest of us, there’s still time to stand up against those who run pipelines through native watersheds, drain our lakes for bottled water, and sell off our ground water for fracking. There’s still time to reconnect.

I know people who do not need to leave their homes for months as long as they can play video games and order in delivery. How much thinking can really be happening in a life like that? Where is consciousness coming from at that point, through a controlled holographic filter of a holographic universe?

I have to be careful here—because one of the groups I’ve gotten the most heat from is gamers! When I’ve done live radio shows, they’ll call in to challenge me on the distinction I’m making between what I deem “real-life” communities and virtual communities. Their point is that the online gaming community is a real-life community, full of deep, meaningful friendships. They have adventures with their friends (via the games they’re playing), they talk about life, and they make acquaintances from all across the world. As they rightfully point out, gamers may be socializing much more than a person who simply goes out to a coffee shop or the bar. And I agree with them. I do think gaming communities can create friendships that are deeply meaningful and significant—and I don’t want to denigrate this.

The problem arises when the virtual community actively interferes with the tangible reality. I don’t want to gender this too much, but I hear from a lot of female friends who have become widows to the gaming consoles in their houses. They complain that their partners have essentially abandoned them for Xboxes and PS4s. These women go to sleep without their boyfriends or husbands, who stay up all hours of the night playing video games. Grown men are disappearing into their basements like teenagers, and suddenly their girlfriends/wives are becoming afterschool moms. See, I told you I’d get myself into trouble. But, we have to talk about this—because there’s a lot more of this kind of virtual romantic estrangement going on than we care to acknowledge. A lot of relationships are getting ruined due to a partner’s immersion in online worlds.

Of course, it’s true that this kind of romantic estrangement happens offline as well—it’s the classic stereotype of the spouse who spends all day “at the office” or “in the garage.” So in some ways, the virtual world is merely an extension of the troubled romantic dynamics already present in our culture. However, the virtual world provides an even more complex form of estrangement, and I suspect we’re going to see an increase of romantic isolation as the world of teledildonics develops (these are remote controlled sex toys that interface with virtual reality). My guess is that within a decade we’ll see people engaging in STD-free online sex and the “games” they play will be fully immersive. When we reach that point, it will be as you say: our consciousness will be controlled through a holographic filter of a holographic universe. And, boy, I hope I’m wrong, but so far many of the dystopian scenarios I joked about in my stories are already coming true.

Philosophers or writers of influence while working on this book?

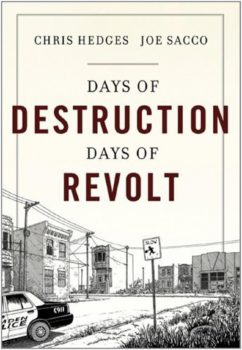

I’m particularly interested in consciousness thinkers, and people like Ram Dass, Jack Kornfield, Martín Prechtel, Terence McKenna, and Alan Watts have had an influence on the ideologies in this collection. Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco’s book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt directly influenced the devastation of the settings. And Dan Savage’s podcast helped shape the relationship/sexual dramas in “Migration” and “Openness.”

I’m particularly interested in consciousness thinkers, and people like Ram Dass, Jack Kornfield, Martín Prechtel, Terence McKenna, and Alan Watts have had an influence on the ideologies in this collection. Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco’s book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt directly influenced the devastation of the settings. And Dan Savage’s podcast helped shape the relationship/sexual dramas in “Migration” and “Openness.”

As for fiction writers, I love the experimentalists. Tom Robbins, Kurt Vonnegut, Tatyana Tolstaya, Jorge Luis Borges, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Ishmael Reed, George Saunders, Karen Russell, Victor Pelevin, and many others. I love how each of these writers experiments with the borders of fiction and the so-called “rules” of literature—they inspire me to take risks with my writing. In some cases I turned directly to certain authors to see how they handled a scene or dialogue. The story “Ice Age”—particularly the scene where the main character journeys beneath the ice—was influenced by Italo Calvino. The son and father’s heart-to-heart conversation in “Migration” was influenced by James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues.” And formalist stories like “Excerpts from the New World Authorized Dictionary” and “A Brief History of the Failed Revolution” were influenced by David Foster Wallace.

Finally, I find a lot of inspiration in the genre-pushing work of musicians like Sun Ra and Fela Kuti, dancers like Pina Bausch, and filmmakers like Charlie Kaufman and Spike Jonze. All of them help show me ways to take risks toward greater sentiment and honesty.

I love Alan Watts. I once heard a recorded lecture where he spoke of two different paths to enlightenment. One path being strict and disciplined, and the other path being chaotic, unruly and undisciplined. This calls to mind your short story, “Moksha,” and the main character, Abe, who goes on a journey in search of enlightenment. Abe puts himself through a variety of mind-bending experiments and it’s quite thrilling to follow him on his path. Would you say that experimentation and enlightenment go hand in hand? What I mean to say is, can experimentation lead to enlightenment? And to further that- is enlightenment a state of mind or could it possibly be nothing more than a single moment of enlightenment that has come and gone?

What a question! Well, you know, I think anything can ultimately lead to enlightenment. Ram Dass tells this great story—from back in the Naropa days when he’d first returned from meeting his guru. All the Americans who’d come to hear him talk would be wearing dhotis and beads and flowers in their hair, and there was this one woman in the audience, maybe 60 years old, in a fancy dress, with her purse, and one of these ornate hats with plastic cherries on it. And the more far-out stuff Ram Dass would say about consciousness, and LSD, and enlightenment, the more she’d nod her head as if she fully understood him. And Ram Dass just couldn’t figure it out. “How in the world does this woman have any clue what I’m talking about?” he kept wondering. So afterwards he goes to meet her, and she tells him that how he’s described enlightenment and the various stages of consciousness is precisely the way she understands the world, too. So he asks her the natural follow-up question: “And how did you come to this understanding of the universe?” And she leans in conspiratorially and whispers: “I crochet.”

I love that story, because it’s a good reminder that we all find liberation in our own ways. I do think one needs to be careful of this philosophy though, because it’s easy to give yourself a get-out-of-doing-the-work-free card (i.e., “Oh yeah, I smoke loads of weed and drink as my way to find liberation!” . . . well, maybe . . . but. . .) All the same, this story has helped broaden the range of what I might think is the path to enlightenment, because it’s easy to get very organized and fanatical and specific about this kind of stuff.

I do think experimentation can help. Experimentation with what though? Well, anything that helps free us from the trap of believing our personalities are who we are. I think this is one of the biggest ways that we become trapped—we believe the things we think (about ourselves, about others, about the world). In turn, we create a personality based on our likes, dislikes, opinions, judgements, past wounding, and hopes for joy—and then cling to these personalities as being “us.” So we need to experiment in ways which helps to free us from this trap of consciousness.

Psychedelics have historically been connected to consciousness and experimentation. There are many indigenous and shamanic tribes who have used plant medicines to have visions and increase their spiritual connection to their community and the cosmos. And you have other methods like sweat lodges, vision quests, breath work practice, etc. which are also aimed at similar goals. These are really great methods which the US would do good to learn from. Quite often our own methods of using such plants/ceremonies are similar to how we use alcohol—to get high/drunk or in hopes of momentary entertainment. Yet, the deep work of healing and consciousness expansion isn’t always a party. It can require a great amount of inner work which includes forgiveness, healing old habits, opening our hearts to love again, and other labor-intensive work. So, I suppose experimentation in this way can lead, perhaps not to enlightenment, but to a greater liberation from the known. But it’s just one way to get there, and there are so many others.

This is what poetry is there for, or experimental fiction, or art, or jazz, or performance, or lovemaking, or parenthood—each of these are methods to experiment with this thing we call life, so that we might be able to understand it a little better. And each of these things is ultimately both liberating and fleeting, which is the whole fun/infuriating issue with this thing called enlightenment.

I used to think I knew what enlightenment meant—that it was a state you could reach (and then you could levitate or transcend reincarnation or have all knowledge . . . or at least glow a little). But over time, I think of it less and less as a state you can achieve. Instead I think it’s an ongoing practice, which has to do with being able to step back from our personality long enough to see that our constructed personalities are simply a form of play. To take them seriously is to forget we’re playing—and so it requires a kind of ease of witnessing, of working through our hang ups (i.e., karma) and continually working toward a state of greater love towards ourselves, others, our enemies, and the world. This is really big work—and it’s the ability to be in this unfolding practice without striving for the idealized state that, conversely, seems to move us more effectively towards this idealized state we call enlightenment. And, as you say, I think it’s also those moments of deep inner quiet and joy which are momentary glimpses of enlightenment—how we can feel simply sitting and watching the rain, or listening to a bird sing, or looking into our lover’s eyes, or being with an old friend in contented quiet, or lifting your child high into the air. There’s a great kind of medicine in all of these things.

Abe, in the story “Moksha,” ends up getting a small taste of this. And I think who Abe is in the beginning of the story (as he’s seeking enlightenment as escape/for the ideal high) was who I was as a teenager, when I first became interested in enlightenment. Abe at the end of the story is closer to where I find myself now—with an acceptance that enlightenment can be found in the mundane details of life just as readily as in the ecstatic states.

Chris Hedges talks about the effects of sacrifice zones on greater society. Cities and towns left with a self-devouring quality after the collapse of corporate companies or factories owned by an elite few. Hedges argues that when societies like this break down, a parasitic elite develops who take advantage of the area (much like Quimbly appears to take advantage of those around him by selling memories in the “Cartographers”). People are disempowered and they don’t have the mechanisms to fight back. They become slaves. I felt a similar strand in this collection. It seemed as though the characters and their worlds had been sucked into some sort of vacuum. Are they living in sacrifice zones? Ghost cities?

Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco’s book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt should be required reading for all Americans. The book was where I first heard the term sacrifice zones (like Appalachia, where coal companies are doing mountaintop removal, or the Dakotas, where the Lakota have been fighting for their lives ever since “Americans” arrived). There’s no way to read that book and not admit that corporations and the government are in collusion to pillage our land at whatever price necessary (and often the human cost is sacrificed in bottom-line economics). We certainly can see this in our own state of Michigan, with fracking interests making water flammable, and our governor making decisions leading to the poisoning of the families of Flint. And things are getting way worse under Trump.

So yes, we’re witnessing the age of the parasitic elite. And I’m trying to depict this within my stories. In “Heartland,” the family is struggling to keep their house by selling off the topsoil of their backyard, and eventually by trading in their morality to make enough to keep surviving. And this is all too true for many out there today—we’re working so hard to achieve some dreamed of “good life” that was promised us, and all the while many of our advances/rewards end up making life worse for others (sweatshop labor, open pit mining for our cell phones, Monsanto seed-patenting, etc). What we’re seeing is a global disempowerment of people due to the corporate influence of politicians and the business elite.

In my collection, you never really get to see the true bad guys. Quimbly might be the one exception—though really he’s just part of a larger disease. But the main players—the CEOs, banking executives, and politicians, who rob the earth and its people, are hidden from the daily lives of the characters in my stories. And I think this is because that’s the way it’s like for all of us, living out here in the real world. Like you say, there’s a way that we feel disempowered and have no mechanisms to fight back. And while the settings of my stories may be a bit more dystopian than where we presently find ourselves, my characters’ struggles are the same of ours. They’re working to be better humans in the face of corporate greed and political avarice, and to figure out what it means to love well as they survive.

What can we expect from you next?

I’m working on my second book, The Lost Traveler’s Tour Guide, a novel comprised of tour guide entries which describe fantastical cities, museums, libraries, restaurants, hotels, and art galleries—each one a universe unto itself. It works primarily in the magical realist vein of Italo Cavino’s Invisible Cities, and Milorad Pavic’s Dictionary of the Khazars. It’s also a kind of autobiography, as each of the destinations is a metaphor for different emotional locations I’ve visited: cities of longing, hotels of joy, museums of heartbreak. Whereas Children of the New World has ties to sci-fi, this new book is rooted in fabulism. All the same, I’m still working with my favorite topics: nostalgia, longing, memory, and love.