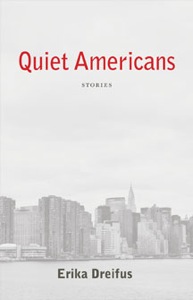

Erika Dreifus, a Contributing Editor here at Fiction Writers Review and at The Writer, is the author of the collection Quiet Americans, published earlier this year by Last Light Studio Books. For FWR, she both inspired and helped run the Collection Giveaway Project for Short Story Month. She recently wrote an essay on “3G” (third-generation) Jewish novelists, highlighting works by Julie Orringer, Alison Pick, and Natasha Solomons, and she has also reviewed Jacob Paul’s Sarah/Sara, Chloe Aridjis’s Book of Clouds, and Midge Raymond’s Forgetting English. Her reviews, essays, poems, and stories have been published in Moment magazine, TriQuarterly, and The Writer magazine, among others. Erika has taught history, literature, and writing at Harvard, and book reviewing for Lesley University’s low-residency MFA program, and she currently works for The City University of New York.

Erika Dreifus, a Contributing Editor here at Fiction Writers Review and at The Writer, is the author of the collection Quiet Americans, published earlier this year by Last Light Studio Books. For FWR, she both inspired and helped run the Collection Giveaway Project for Short Story Month. She recently wrote an essay on “3G” (third-generation) Jewish novelists, highlighting works by Julie Orringer, Alison Pick, and Natasha Solomons, and she has also reviewed Jacob Paul’s Sarah/Sara, Chloe Aridjis’s Book of Clouds, and Midge Raymond’s Forgetting English. Her reviews, essays, poems, and stories have been published in Moment magazine, TriQuarterly, and The Writer magazine, among others. Erika has taught history, literature, and writing at Harvard, and book reviewing for Lesley University’s low-residency MFA program, and she currently works for The City University of New York.

Erika’s debut collection, Quiet Americans, is largely inspired by the histories and experiences of her paternal grandparents, German Jews who escaped Nazi persecution and immigrated to the United States in the late 1930s.

Andrew Furman (author of Contemporary Jewish American Writers and the Multicultural Dilemma) had this to say about the book:

In searing, pitch-perfect prose, Erika Dreifus evokes in Quiet Americans the heart-wrenching intersections between domesticity and war. Drenched in the blood-soaked history of the Holocaust—yet attentive to those quietest moments between husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, parents and children—these stories gather unexpected force sentence by sentence, page by page. On several occasions during my reading, I needed to remind myself to breathe.

I read Erika’s Practicing Writer newsletter and blog faithfully for several years before launching Fiction Writers Review, so Erika—as a writer about writing and a fairy godmother of writing resources—was an inspiration to me long before we met. I still remember the thrill I felt when she mentioned FWR on her site for the first time; not long after, I convinced her to write a review for us. Reading the galley of her deeply moving collection and re-reading it in published form, I was again awed by Erika, this time by her brilliance as a fiction writer herself.

This interview took place over coffee during AWP 2011, a day after attending the exciting panel she organized and moderated, “Beyond Bagels and Lox: Jewish-American Fiction in the 21st Century,” and just hours after FWR’s own panel on criticism in the 21st century, “The Good Review.”

Interview

ANNE STAMESHKIN: First, let me say again how impressed…no, that’s too cold…how struck I was by Quiet Americans. And I enjoyed your panel on Jewish fiction yesterday. I only wish there’d been ample time to argue with a particular woman in the audience, the one who announced [to your panel of Jewish fiction writers] that she didn’t like to read Jewish fiction because she wants to know “what really happened,” not something “made up.” In your case, some of the stories are even more than half-true, based on your family’s experiences across three generations. So tell me—and that naysaying woman!—why you chose to relate these stories as fiction. Did you ever consider writing them as essays instead, or have you written essays about your legacy or your own experience as a third-generation American Jew?

ANNE STAMESHKIN: First, let me say again how impressed…no, that’s too cold…how struck I was by Quiet Americans. And I enjoyed your panel on Jewish fiction yesterday. I only wish there’d been ample time to argue with a particular woman in the audience, the one who announced [to your panel of Jewish fiction writers] that she didn’t like to read Jewish fiction because she wants to know “what really happened,” not something “made up.” In your case, some of the stories are even more than half-true, based on your family’s experiences across three generations. So tell me—and that naysaying woman!—why you chose to relate these stories as fiction. Did you ever consider writing them as essays instead, or have you written essays about your legacy or your own experience as a third-generation American Jew?

ERIKA DREIFUS: I have written a couple of essays, but I never thought about writing a personal or family memoir about these stories, though they are, as you know, based on and inspired by my family. I have written nonfiction pieces about my handling of this legacy. I did an article for the Boston Globe when I got a German passport, and I described the process of getting it and why I had gotten it and decided to become a German citizen—a dual U.S.-German citizen. A lot of the bare-bones history behind these stories is in that essay.

ERIKA DREIFUS: I have written a couple of essays, but I never thought about writing a personal or family memoir about these stories, though they are, as you know, based on and inspired by my family. I have written nonfiction pieces about my handling of this legacy. I did an article for the Boston Globe when I got a German passport, and I described the process of getting it and why I had gotten it and decided to become a German citizen—a dual U.S.-German citizen. A lot of the bare-bones history behind these stories is in that essay.

And I’ve written an essay, a conference paper, called “Ever After? History, Healing, and ‘Holocaust Fiction’ in the Third Generation.” (For those who want to read it, I should mention that it includes a lot of British spellings: it was for a conference in London, and the publisher was in Germany.) Writing that essay helped me process and figure out more how my writing—my fiction that I’d been writing—connected to the history. The fiction allowed me certain freedoms—ways to focus on what I’d consider to be more “dramatic” moments, and really push to the corners the less dramatic things.

My story “For Services Rendered”—about a Jewish doctor who was given leave to emigrate from Germany because he had treated the daughter of a high-level Nazi—the complexity of that idea had fascinated me; the bit of truth was that when my grandmother came here, she became a nanny for a family, an affluent Jewish American family whose daughter was the patient of this pediatrician, a German refugee who had been told by his Nazi employer back in Germany, “You should get out of here.” And my father, as I was writing, he said, “you know, you could look this guy up; I still have his name, and you could do a nonfiction piece…” but I said, no, that’s not what I want to do. I wanted to explore it a different way. I almost didn’t want to know what the guy’s real name was—and I didn’t use his real name.

Oh, and I think the woman in the panel, the one who doesn’t like Jewish fiction…I’m pretty sure she has a nonfiction book coming out.

Ha! That’s one way to get publicity… But you do hear people saying “Feh, novels, stories. I want to read what’s true” across the board, about all kinds of fiction. It was interesting to hear it attached specifically to Jewish fiction…that desire to know what “really happened,” about the Holocaust. Yet no amount of sheer “what” can really ever tell us why or how this happened. Do you think there’s a way of getting at even more truth through fiction…when you can give a whole story, or as much as you choose to? Fewer and fewer people remain to tell their stories—and the prospect of reconstructing “true” narratives becomes ever more elusive. But I’d argue that a collection like yours refutes the notion that a book of fiction can’t portray what really happened, at least in a larger sense.

I agree, and I think a good example of this is in my story “Homecomings” [about a Jewish immigrant couple making their first trip back to Germany]. My grandparents did go back to Europe for the first time in 1972; they did stay with French cousins, because they—my grandmother—did not want to sleep in Germany.

In “Homecomings,” the characters were there during the Munich Olympics and the massacre. Were your grandparents?

They were not. And that’s the fiction! But at some point it occurred to me that they must have been there right before. And the reason I know they weren’t there during the Olympics is that in early September of ’72, they were in charge of me—my mom was away visiting a friend and the friend’s brand-new baby in the hospital, and my dad was at work, and I fell and broke my tooth, and it turned purplish-black and chipped, and my grandparents were very upset with each other—you know, somebody wasn’t watching her! I was three. So I knew they were not away in September. But my grandmother told me that they went back that year, and she just sat outside her old building and cried. She just cried. She couldn’t even get out of the car and was not interested in going into the apartment, which actually my father and I did in 1990.

We went back, and I think that’s another thing that helped the story. I had been to Mannheim, and I had seen the apartment and the street and the office, and the descriptions of the city itself…all the things that are mentioned in “Homecomings” are based on these real places and what I saw.

The flower shop in Mannheim / photo credit: The Dreifus Family

We knew there was this flower shop where she and her father used to go, and we found it, and there’s a picture of me in front of the office building where my great-grandfather once had his business. And my grandmother was still alive then in 1990, and when we got the pictures developed and she saw them…I should say that she wasn’t a crying sort of person. She was tough; there were few things that could make her cry. But she was just hit, with everything, when she saw a picture of me in the courtyard of their apartment building.

Ifflenstrasse, the street 'off the city's main ring' where Erika's grandmother lived / photo used with permission of The Dreifus Family

There’s that blurring of generations in moments like that. Yesterday during the panel, Margot Singer talked about her cousin’s realization, while visiting the Czech Republic, that this is where I would have grown up if things had been different. There is a line in one of your stories, after German Jews have relocated to the U.S. “Doesn’t everyone want to go home?” asks the husband. And his wife is just silent.

That idea of “home” and having lost one is powerful…in 1989, my grandparents went back again. My parents had given them a trip for their 75th birthdays. Again they didn’t sleep in Germany, but they did go into Mannheim. I think they went to go change money in a bank and some man was trying to tell my grandmother that she should move back to Mannheim, that she should come “home.” And she told us, “I really let him have it!” (Laughs.) She said, “I told him, ‘America’s my home!’”

Not a quiet American!

That’s the funny thing. No one who knew her would call her quiet…but my grandfather, he was. Though I don’t know how much of that was the language. I don’t think he ever felt comfortable in English. The way a conversation went with them on the phone, is that I’d have to remind her that I wanted to talk to him, too. And she would give him instructions: Grandpa, talk!

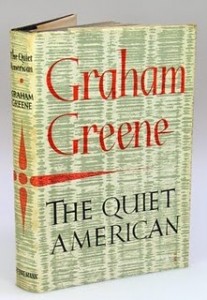

Speaking of the title, I love it, and it feels so fitting for the collection. In every story, even the ones that don’t take place in America, silence plays a powerful role. In your story “Matrilineal Descent,” for instance, Emma stays quiet while her heart breaks slowly over time—with drastic consequences, as this “quiet” still allows for vengeance. What did you want Quiet Americans to mean, or to suggest to readers? And were you referencing the Graham Greene book—the singular American to your plural?

It’s clear that I was influenced by Greene’s title to some degree—hey, it’s a great one—but I’ve actually worried about how to respond to questions about it. There isn’t an intended direct connection between that novel and my collection. My book isn’t an homage to or a criticism of his.

It’s clear that I was influenced by Greene’s title to some degree—hey, it’s a great one—but I’ve actually worried about how to respond to questions about it. There isn’t an intended direct connection between that novel and my collection. My book isn’t an homage to or a criticism of his.

In most story collections, as you know, there is usually a story that shares its title with the collection…but the funny thing is that the title story wasn’t part of the initial book! The collection has gone through so many different iterations.

Tell me more about the book’s genesis. How did it take shape?

Three of the stories in Quiet Americans started out as pieces I wrote during my MFA program. I wrote a whole collection for my thesis, and the working title then was The Unchosen, because I had a story called “The Unchosen,” which has never been published, although I’ve submitted it everywhere. Alas, it lived up to its name: it was never chosen! (Laughs) Then I had a very long story called “Reparation,” so then that was the title for a long time. And then I decided that even though that story came close at a couple of places, there were various issues about it—one being of course how long it was—that made people not want to take it. But once I removed it from the book, I had to come up with yet another title.

You know that some of the story titles in the book are in other languages. “Lebensraum”…you know a lot of people—even really educated people—don’t know what that is. And “Mishpocha” is sort of limited to the Jewish reading community, so even though I felt that Lebensraum really was a good title for the whole collection—I could see it working well—I didn’t want to use it because I didn’t want to alienate people right away.

However, you did keep this title—and “Mishpocha”—for the stories themselves. Why?

I have a PhD in European history, but my potential readers are not necessarily in this specific field. And you can get through college and definitely high school without doing much European history these days! A whole book with an unfamiliar title might be off-putting. But I wanted to keep “Lebensraum” as the title of the story because I believe most short-story readers are curious and brave enough to read something under an unfamiliar word and then maybe even look it up.

So, getting back to the issue of the title…then I returned to the stories that were left, and “For Services Rendered” doesn’t really do it for the whole book, and “Homecomings” was, I felt, a little bland, and then I realized I could take a piece from a longer story I wasn’t going to able to use, the one that “Quiet Americans” used to be part of, and it really worked. As soon as I thought of this, I knew it was right. But it was a long time coming.

And that title can mean a lot of different things…are you quiet from fear? Are you assimilated when you’re quiet? There’s powerful gratitude felt by the American tourist in “Quiet Americans” when the British war vet speaks up to the insensitive Berlin tour guide.

I was surprised by how much I liked that this story was written in the second person. As many of FWR’s writer-readers know, that can be hard to pull off. Why did you make this choice for this particular story?

First, I love that you like the choice. A lot of editors who saw the story said, “Great story, but I just have a personal distaste for the second person.” I hope that the piece earns this through quiet…the writer is asking the reader to speak.

I agree. Reading it, the story feels confrontational in the best way. It feels like “you” are the one in this uncomfortable, even hostile, situation. And what would “you” do? it asks. Would “you” be able to speak up? It’s a different “you” of course—but it reminds me of the character-narrator addressed in a popular Lorrie Moore story, “How to Become a Writer…”

I agree. Reading it, the story feels confrontational in the best way. It feels like “you” are the one in this uncomfortable, even hostile, situation. And what would “you” do? it asks. Would “you” be able to speak up? It’s a different “you” of course—but it reminds me of the character-narrator addressed in a popular Lorrie Moore story, “How to Become a Writer…”

I love what Moore does with the second person in other Self-Help stories, too. “How to Be the Other Woman,” for one.

Agreed. I see a kinship between her second-person characters and yours…that implied sense of universal experience as well as an individual one.

I’m glad that came across! Lorrie Moore is one of my favorites.

After reading the three more directly linked stories in Quiet Americans, the trilogy beginning with “Matrilineal Descent,” I have to ask: did you ever consider shaping your book into a novel-in-stories, focusing on these recurring characters (who represent three generations of the same family, spanning twentieth-century Germany to present-day New York City)?

Yes and no. I have other stories, some from my MFA thesis, but they’re a little repetitive in terms of theme. So initially I did have ideas about putting more stories about this family (or versions of them) together in a book, but it just didn’t really work. It felt a little artificial…stretched. Maybe it was because I did not plan. If I had really set out to write the linked stories, then I could have done it. But on the other hand, I’ve tweaked them quite a bit…they’re not the same stories as the ones I originally wrote. For the book, I even changed some of the names to make the stories more cohesive…in “Homecomings,” I did this. It wasn’t always as obvious that the refugee couple in “Homecomings” was the same as the one in “Lebensraum.” Although in my mind, they were both inspired by my grandparents, I had initially named them differently and was originally imagining two different families…but then I realized they were in fact the same couple…and I went back and changed some details in one of the stories to fit this. It felt more right this way than it had been when I was trying to treat them differently.

One sort of interesting thing that I came to realize as I was shaping the collection is that, in a way, the “Quiet American” story could also be considered, even though the names aren’t used, to be a continuation of “Homecomings.” Because the details are really the same…the grandparents from Germany, the mention of Stuttgart for the consulate, and there are two grandchildren mentioned. So readers could decide that this is another story of that family, but you don’t have to decide that.

In these crazy publishing times, why write a collection, period, instead of a novel?

Actually, I did write a novel. When I went to the MFA program, it had just gotten agented, and I’d done a lot of revisions for the agent, and she was sending it out—so I didn’t want to workshop it. I didn’t want more feedback at that point; of course it was one thing to get notes from editors at houses, but quite another to bring it back into a workshop. So I started writing these stories, and they kept coming. And one really good thing about my program was that it demanded a lot of production. We had to present 8-25 pages twice during the residency week and then four times during the semester.

That’s a lot!

It is, and some people submitted multiple revisions of the same story or novel chapter during a semester, but I never did that. I mean, I did workshop “Lebensraum” and “Homecomings” in revisions during two different semesters with two different groups of people, and I may have submitted early iterations of “For Services Rendered” twice during the final semester, which was an especially trying one, but I wrote over twenty stories during my MFA years.

Why did you choose to do that instead of workshopping revisions?

There was a huge advantage to me of just getting all that material down and then going back and revising later. And this is why I wasn’t really focused on that novel. It was never published, and it remains the novel in the drawer, the proverbial first novel. To the question “Why short stories?” the practical answer is that this is what I worked on during those years. And of course I love reading short fiction, too.

What were you reading when you worked on this collection, and who are some other Jewish writers, or artists in other mediums, who inspire you? Who would you recommend to other people who are interested in reading and writing Jewish fiction?

I would recommend everyone who was on the panel, and everyone we recommended during it… [EDITOR’S NOTE: Scroll down for a grand reading list!] Some short story collections that have really spoken to me include Margot Singer’s The Pale of Settlement, and one on the after-history of the Holocaust is the wonderful novella-and-stories Awake in the Dark, by Shira Nayman. (One of the stories from it, “The House on Kronenstrasse,” appeared in the Atlantic’s Fiction Issue in 2005, and I interviewed her for JBooks. Both Nayman’s and Singer’s were books I felt a kinship with, ones I wished I’d written! Obviously with Singer’s there are stories about Israel that I never could have written, but I just admired it so much and felt so connected to it.

I would recommend everyone who was on the panel, and everyone we recommended during it… [EDITOR’S NOTE: Scroll down for a grand reading list!] Some short story collections that have really spoken to me include Margot Singer’s The Pale of Settlement, and one on the after-history of the Holocaust is the wonderful novella-and-stories Awake in the Dark, by Shira Nayman. (One of the stories from it, “The House on Kronenstrasse,” appeared in the Atlantic’s Fiction Issue in 2005, and I interviewed her for JBooks. Both Nayman’s and Singer’s were books I felt a kinship with, ones I wished I’d written! Obviously with Singer’s there are stories about Israel that I never could have written, but I just admired it so much and felt so connected to it.

Have you spent much time in Israel?

Not enough. I went for the second time last year, in October. And I first went there in 1988. There’s not much I would redo in terms of my life, but one thing I wish I would have done when I was younger would be to have applied for a fellowship and to have spent more time there—a year or more, maybe—and to have become fluent in Hebrew. But I graduated from college the year of the first Gulf War; I remember my college roommate’s sister was in Israel in January of 1991, and it was a really scary time for American families to send their kids there. It would have probably been amazing to go when I was younger. But maybe I’ll get the opportunity for a longer stay somewhere in the future. I hope so. I do feel very attached to Israel.

And how much time have you spent in Germany?

Not a whole lot. The country I really know best outside of the United States is France. And I began this love affair with France and all things French when I was in middle school and started studying French, French literature and history…but the first time I went to Germany was 1990, during my semester in France. And it was right after the wall came down.

It was an exciting time. I brought back pieces of the wall. East Berlin—what had been East Berlin—was in bad shape. The pictures that I have from that trip…well, let’s just say the city has been completely reborn in the last twenty years.

Then I went back again a few months later with my dad. He was on business, and we went in the summer to Mannheim. Then my dad, my sister, my mom, and I went in 1993, and then I went again, to Stuttgart, in 2004.

During one of those trips, did you have an experience like the tourist in “Quiet Americans”? Or was this something you imagined (or feared) might happen?

I don’t know if you experience this, too, but when I write fiction that is at least partly autobiographical, I sometimes have trouble remembering what I’ve made up and what’s the real memory. And I definitely feel that way about this story… The idea of the RAF soldier…that didn’t happen on my bus. I got that idea from a conversation with someone else who had a similar experience. Some aspects of that story are definitely true. The reason I went on the bus tour is that I do have a terrible sense of direction, and I’ve made a habit since my first trip to Paris: get on the bus and figure out where everything is. But I can’t say with 100% certainty that I had what was my narrator’s impression: that this guide was very much focused on how everything in Stuttgart was destroyed or rebuilt and didn’t talk about much else.

When I read the story, I find myself questioning that memory. Did it really happen, or was it just my feeling?

And I’ve had this doubt emerge about a number of stories I’ve written. So to get back to that earlier question, this is another reason I’m so glad it’s fiction! Because if it were a memoir…I’m one of the people who believes that a memoir should be as true as the author can possibly make it. I don’t want to have an A Million Little Pieces moment. So even for fiction, I want to be very careful to say that I don’t remember exactly what happened.

As a Jewish American, did you grow up feeling more like part of a community, or like an outsider?

Growing up in Brooklyn, almost everyone we knew was Jewish. There were some Italians and Italian-Americans, Roman Catholics, but then we moved to the suburbs and we were the only Jews on our block, and I was the only Jew in my fourth-grade class, and it was a culture shock. And in the larger middle school and high school, and then in college, I got used to being around Jews again, and then at the MFA program, I found myself the rare Jew again. In France, as a high schooler, I lived with a family in the Alps, and one of the daughters asked me the first day I was there, “So, you’re Catholic?” I said, “No.” “Well then you’re Protestant.” And I told her I was Jewish. She said, “Really? I’ve never met a Jewish person before.” I slept in her room, and there was a cross over the bed. There was this back and forth, growing up, between belonging and being an outsider.

And I come up against this idea, from within the literary community, that being Jewish is “not so special,” that everyone’s met Jews and knows about Jews.

In cities like New York, it’s likely most people will run into someone Jewish at some point, but it’s amazing how segregated many communities…even urban ones…remain. Growing up in the burbs of a small city in Pennsylvania, I was asked more than once—and not maliciously!—if I had horns.

Yes! People say that everyone’s assimilated, and yesterday one of the panelists mentioned that he doesn’t want to read any more about so-called “obliterationist anxiety,” and my chest tightened. There are little things. I remember moving to New Jersey and there was a dance class that many of my classmates took, but it was at a country club that didn’t admit Jews. And I didn’t even want to dance in that class—I was so clumsy, it would have been a horrible thing!—but just knowing that something like that exists, when you’re 9 years old, and knowing my grandparents’ background, and watching the Holocaust miniseries on television (it had just aired the year before), which I probably shouldn’t have watched at that age, but I did….

What role do you think Israel, or the idea of a Jewish state, plays in this concept of “obliterationist anxiety”?

For me, personally, it’s all significant and everything is tied together. But it’s a complicated subject, Israel, especially in the context of the constant public discourse about it.

This brings up something very important to me and my writing more generally. In my history education, I was graced over many years to work with Stanley Hoffmann, technically a political scientist, but really a multiply-gifted individual who is really interested in moral issues and how complicated they are. I was his TA for his class on France between 1936-1944, and in that class and elsewhere, he really helped me not see things in black and white, how hard it is to make moral choices and, as he has said, that “it takes a lot of courage to be a hero.”

In “Mishpocha,” for instance, what happens on that street…that happened to me when I was walking in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And of course people in my parents’ generation read the story and say, “Well, of course you didn’t say anything. Who knows what might have happened to you?” But people in my generation—our generation, and those a little younger—those people can get upset when they read this, that I didn’t say something. When the incident came up in a workshop, there was quite a discussion. Now, I can be brave in some contexts: I’ll speak up in a class or curriculum committee and say, “Hey, this should really be on the syllabus!” But in other settings, like in that situation on the street, I’m not brave at all.

I wouldn’t know how to write about that moment in nonfiction. It was so searing to have it happen, but being able to bring it into a fictional piece felt…important, and I hope that it helps scaffold that story and gives more insight into the diversity of the Jewish American experience: this man was raised as a certain kind of Jew, and his wife as another. We live in such a multicultural society—but various online message boards will be teeming with rages about people “appropriating” other cultures. We all live together, and how limiting does it become to only write about people who are just like you? Unfortunately my “Reparation” story—the longer one I mentioned before—didn’t work for a number of reasons, but in it, I was trying to get at some of the issues between African Americans and Jews. Perhaps it was worrisome to editors that as a Jewish author, I was writing African American characters…but we’re not living in a Jewish ghetto. We do interact. So it feels unnatural to only have my Jewish characters interact with other Jews.

It’s obviously a complex question. Of course we want to get things right, and there’s often a fine line between appropriating and inhabiting…but writing just “what we know” or what we are is awfully limiting. After an Edward P. Jones reading I attended, someone asked him what his thoughts on writing other genders, races, etc., were. In his novel, The Known World, which I love, he wrote white women as convincingly as he did African American men, and he claimed to feel pretty confident doing so. But he admitted to feeling suspicious of white authors who try to write black characters—and really of any majority trying to write from the POV of any minority. I can understand his perspective on this (again, you’ve got to get it right!), but I wonder how, or if, we can get to a place where readers and editors can look at an author photo and not put up a wall if the author has a different gender or background from the characters.

Or a different life experience. I’ve been in workshops in which some participants—who were mothers themselves—knew I don’t have a child, and occasionally someone would just put up a wall, as you said, at certain things in my stories, saying, “No, that’s just not how it is when you have children,” or “She wouldn’t feel that way three weeks after having a baby,” or “She wouldn’t fit into her clothes yet.”—but these things vary so much from mother to mother, from person to person. The idea that I had overstepped by even trying to imagine motherhood…that you’re only allowed to write about certain things because you’ve lived them…to me, it contravenes the idea of fiction.

I find that if a character comes across as not believable, not real within a story’s world, that’s when I go to the author photo and think something generically judgmental…you know, “Come on, really, male writer? You think women are like this?”

I know what you mean. But then you get writers like Jacob Paul. I was so impressed with Sarah/Sara, the character and the book.

He wrote the character of Sarah/Sara beautifully—her voice, everything. I forgot the author was a man for huge spans of time.

His book gets into many interesting topics that I’m invested in, that I want to write about: 9/11, and Israel. It was a pleasure to review.

You’ve been writing book reviews for a while now—for as long as you’ve been writing fiction…

And teaching them, too!

I didn’t know that. Where did you teach writing reviews, and what was the context? I just learned today that Penn State’s MFA program offers a course on reviewing.

Overall, I’m surprised that more writing programs don’t offer courses in writing reviews. When I was freelancing and teaching, I taught a course online in writing book reviews. And through the Lesley MFA program, which has an extra interdisciplinary or independent study component, I ran a book review class for several semesters until I took a job at CUNY.

As discussed at the [AWP] Good Review panel, it can be hard—or at least problematic—to write reviews that are overly critical when you’re a writer yourself. And some people make the argument that writers shouldn’t be critics, that we have too much personal stake in the market/community, or some kind of ulterior motive. But there are huge pluses, too, right, to donning both hats? Let’s spin this toward the positive… What do you think are some advantages of being both a writer and a reviewer of books?

As discussed at the [AWP] Good Review panel, it can be hard—or at least problematic—to write reviews that are overly critical when you’re a writer yourself. And some people make the argument that writers shouldn’t be critics, that we have too much personal stake in the market/community, or some kind of ulterior motive. But there are huge pluses, too, right, to donning both hats? Let’s spin this toward the positive… What do you think are some advantages of being both a writer and a reviewer of books?

Charles Baxter made the excellent point that if you do workshopping and critiquing correctly, that’s actually a lot like reviewing. And ideally, being able to write a good critique about someone else’s work helps you learn about the craft yourself. And that’s sort of how I feel about reviewing, especially the reviews I do for FWR, which focus at least in part on craft elements, and which are written largely for an audience of fiction writers, and which review the work as fiction. The issues that come up in writing about Jacob Paul’s book—the use of point of view, a man writing a woman’s voice, and how a novelist or short-story writer can write successfully about these huge events (suicide bombings, 9/11)—it really does help clarify the way I think about these issues and how to frame them, craft-wise, in my own work.

Of course the review should first and foremost say something about another person’s work: the act of writing about it, of reviewing, helps focus your thinking about it. But doing so can only help your own work.

And is there an advantage to the community aspect of being a writer-reviewer? Do you like the idea of authors reviewing each others’ work out there. Do you like the idea of being reviewed by a fellow fiction writer, or would you prefer to be reviewed by a critic who identifies first and foremost as a critic?

One of the things I’ve really loved so far about my book being released is seeing how reviewers respond to the book; I’m thrilled that they get it. Some of them have been fiction writers, and they really seem to understand what I’m doing. Whether that’s because they’re just innately really smart [laughs], or because they’ve really thought about what goes into writing fiction because they do it themselves, I don’t know, but it’s good to have writers review other writers.

But it’s also hard…in another review-focused panel yesterday, they talked about negative reviews. I try not to write many negative reviews…I’ve written some, but not many. Recently I did write—for the Jewish Journal—a fairly negative review of a work of fiction in translation, an Israeli author’s book. I criticized both the translation and the story itself. Disclaimer: I can’t read Hebrew beyond street signs, but I could tell the translation was clumsy because it just wasn’t working in English. And I was troubled by the overall jumpiness and shifts in points of view: the two narrative strands weren’t integrated very well.

I wrote a pretty mixed review on an anthology of Jewish fiction called Promised Lands. It was scary to say negative things about it because some of the authors in there were quite acclaimed, and many of the stories in it were quite good, wonderful even…but some were not. Mostly I had concerns and questions about the way the larger book was put together, and I voiced these. These pointed to larger questions about how literary anthologies are put together, and I tried to broaden it to that discussion.

But mostly I try to review books of fiction that I can recommend to readers, books I admire and want others to admire and enjoy, too. And if we can talk about fiction as fiction, too, that’s wonderful. I feel so grateful to have lucked into this community at FWR. It’s like being part of an “ideal cohort.” I’m excited to continue working with the site—especially on our annual celebration of Short Story Month.

We love that you’re part of the FWR family. Thanks for taking the time to talk about your collection!

Further Links and Recommendations

• Albert, Elisa. How This Night Is Different (2006).

• Amend, Allison. Stations West (2010).

• Brown, Danit. Ask for a Convertible: Stories (2008).

• Brown, Rosellen. Half a Heart (2000).

• Chabon, Michael. The Yiddish Policemen’s Union (2007).

• Foer, Jonathan Safran. Everything Is Illuminated (2002).

• Furman, Andrew. Alligators May Be Present (2005).

• Goodman, Allegra. Kaaterskill Falls (1999).

• Hamburger, Aaron. Faith for Beginners (2005).

• Haworth, Kevin. The Discontinuity of Small Things (2005).

• Haworth, Kevin. “The Scribe” (2009).

• Horn, Dara. All Other Nights (2009).

• Kadish, Rachel. From a Sealed Room (1998).

• Leegant, Joan. Wherever You Go (2010).

• Litman, Ellen. The Last Chicken in America (2007).

• Lowenthal, Michael. Charity Girl (2005).

• Mirvis, Tova. The Ladies’ Auxiliary (1999).

• Obejas, Achy. Days of Awe (2001).

• Orringer, Julie. The Invisible Bridge (2010).

• Paul, Jacob. Sarah/Sara (2010).

• Reyn, Irina. What Happened to Anna K. (2008).

• Rosenbaum, Thane. The Golems of Gotham (2002).

• Setton, Ruth Knafo. The Road to Fez (2001).

• Shteyngart, Gary. The Russian Debutante’s Handbook (2001).

• Singer, Margot. The Pale of Settlement (2008).

• Sofer, Dalia. The Septembers of Shiraz (2007).

• Solomon, Anna. The Little Bride (2011).

• Stern, Steve. The Wedding Jester (1999).

• Vapnyar, Lara. Broccoli & Other Tales of Food and Love (2008).

• Weber, Katharine. Triangle (2006).