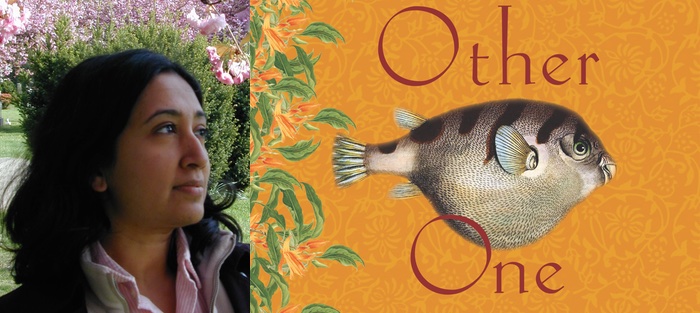

Every now and then you meet a writer whose voice is so fresh and exciting and whose work is not only moving, but important—and you can’t wait for everyone else to discover them. For me, Hasanthika Sirisena is one of those writers. We met in August 2009 as scholars at the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference in Vermont, and I was immediately drawn to her both because of her stories and her thoughtful, generous personality: we spent many hours talking books, craft, and the writing life, and have stayed in touch ever since.

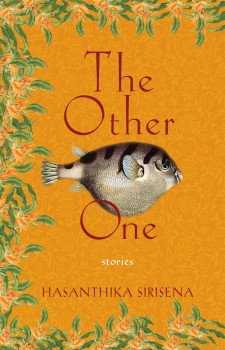

So I was thrilled when Hasanthika’s collection The Other One won the University of Massachusetts’s Juniper Prize. The ten stories in this collection center around Sri Lankans struggling with the civil war and its aftermath, but the human relationships are always front and center here: a divorced mother must confront her husband’s new relationship and a visit from an unexpected guest; the daughter of a policeman comes face to face with her father’s complicity in the brutalities of war. In each story, razor-sharp language, flashes of humor, and deep empathy abound.

Reviewers may be tempted to call The Other One a book “about” Sri Lanka, but I’d argue that it’s really a collection about crossing boundaries–or perhaps more accurately, scrutinizing boundaries and finding that they’re more porous and permeable than they seem. Hasanthika has spent time all over the globe—born in Kandy, Sri Lanka, she grew up in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, and has lived in London, New York City, and most recently central Pennsylvania, where she is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Susquehanna University—and unsurprisingly, she brings a global sensibility to her fiction, as well as a keen awareness of what ties us all together.

Hasanthika and I spoke via email about The Other One, the genesis of her stories, craft, and—of course—cricket.

Interview:

Celeste Ng: This is your debut collection (huge congrats!)—but like most writers, you’ve been honing your craft for years. You received a Rona Jaffe Writers Award in 2008, and you’ve been publishing stories in prestigious journals like Glimmer Train and Narrative for quite some time. How have you noticed your writing changing over time—in subject, style, theme, etc.?

Hasanthika Sirisena: I have found myself tilting very slightly to surrealism. I’m particularly fascinated with writing stories that look on the surface like realism but then take a subtle twist—like “Unicorns” in which you’re not supposed to be able to tell if the women are bankers or ghosts or banker-ghosts.

Why do you think you’re leaning in that direction?

I’ve been reading a lot of poetry lately—particularly James Dickey. He describes his style as ‘country surrealism’ and I’ve fallen in love with that idea myself. This type of surrealism bases itself in the real—realistically rendered characters and setting—and then introduces a tinge of the irrational, of the dreamlike.

What other authors working in this vein do you admire?

Julio Cortazar. Roberto Bolano. Ben Marcus does this in his latest collection Leaving the Sea. Kelly Link. To name a few.

You and I first met at Bread Loaf, and you’ve also been to Yaddo and MacDowell. How have these residencies and fellowships influenced your work?

Yeah, that Bread Loaf experience was formative. I met so many wonderful writers who have become good friends—you, [fiction writer and journalist] Marie Mockett, and [poet] Tomas Q. Morin, for example—and so many members of our cohort there have gone on to successful careers—actually every one of them, now that I sit here and list people. My experience at Yaddo and MacDowell was similar. It’s not just the time to write but you live 24/7 in an environment that cares about writing. They do everything for you so that you can be a writer full-time. That doesn’t happen in real life!

Most of the stories touch on the war in Sri Lanka in some way, and “The Chief Inspector’s Daughter” reflects on it quite directly: “Muslim/Sinhalese/Tamil/Burgher. UNP/LTTE/JVP/JHU/TNA. Royal/Thomian. There are too many choices. But still, they demand that I choose.” In every story, characters are forced to make difficult choices of some kind. Yet the collection’s title almost suggests that no matter what they choose, they’ll always be looking back with regret on “the other one,” the path not taken. Are you optimistic about human relationships in general?

That’s funny. I don’t quite read the title in the same way (though I love your interpretation, Celeste). For me it’s a metaphor for the othering that goes on in all societies and all cultures. Oh, that person over there. He’s the other. That list you quoted is a list of ‘others’ in Sri Lanka (though we do that everywhere).

But I wanted in my stories to take some small step, through inhabiting characters very unlike me, of attempting to transcend my own stereotypes. I don’t think that othering has to be the case, and that’s where the short story and the short story collection become important. Short story collections offer multiple characters, multiple versions, multiple viewpoints, and any good short story writer is going to feel compassion for each and every character and viewpoint. So, yes, I’m an optimist simply because I’m a short story writer.

I’d never thought of a short story collection as deliberately combating othering, by virtue of including an array of voices. I love that. Do you find yourself drawn to stories in particular, and if so, why? Would you ever want to write a longer work? (There’s such a bias in publishing towards novels; so much more I could say here, but won’t!)

I’d never thought of a short story collection as deliberately combating othering, by virtue of including an array of voices. I love that. Do you find yourself drawn to stories in particular, and if so, why? Would you ever want to write a longer work? (There’s such a bias in publishing towards novels; so much more I could say here, but won’t!)

I definitely find myself drawn to stories. Short stories have such an impact and I love that this can result from one deftly delivered blow or from creating a cacophony. I’m supposed to say I’m writing a novel, right? But every day I find myself wondering if I just couldn’t be a short story writer.

Short stories always get so little credit, but I love them. Sometimes I think they’re more powerful than novels, because they’re so concentrated.

I’ve been waiting for a collection from you. When’s that happening?

Ha! Maybe someday. Having been working on a novel for so long myself, it’s hard to get back into the intensity of language and situation you need for a short story—something I think you do so well in each of these pieces.

I read “The Other One” as the most hopeful of the stories in this book—in many ways it’s a story of successful reinvention. The narrator says, “Most Americans, when they think of cricket, think of men in white running leisurely across fields of grass. It’s a game of colonials. That’s not true anymore. It’s our game now—the subcontinent’s. We’ve taken it and made it our own.” In cricket, as you mention in the story, “the other one” has a particular meaning: it’s a whole new move invented by Pakistani spin bowler Saqlain Mushtaq. I know you’re a huge cricket fan yourself—was it hard to work cricket into a short story? Fun?

I love cricket but I’ve never played it. So I read a lot of blogs kept by players for small amateur leagues here in America, and I even went to a Cricket League of New Jersey match. Speaking of stereotypes. I really tried to imagine what it might be like to be a bit of a jock. That was fun because I was really trying to imagine the life of someone different than me (since I’m in no way a natural athlete).

What’s your writing process like?

I usually start with a question. Maybe an image sparks the question. Or I’ll be engaged in a conversation. So, for example, after a conversation that I had with my cousin in Sri Lanka about spin bowling, I began to realize that a woman could, possibly, bowl against a male batter (if the batters weren’t professional players). And then I asked myself a question—what if a woman spin bowler was asked to join a cricket team? The story, “The Other One” flowed naturally from that question.

In many stories, there’s a theme of submerged, yet inescapable, family obligations: in “War Wounds,” the main character is torn between joining her husband in Australia and continuing to care for her injured brother. In “Pine,” Lakshmi hosts a priest as a favor to her uncle, even as she juggles her two young children and her ex-husband. And in “The Inter-Continental,” the narrator must entertain—and protect—her friend’s young cousin. What draws you to this particular subject?

My family. They keep calling. (But I’m grateful. Don’t get me wrong. Otherwise, I’d get no phone calls whatsoever.)

The cover of the book features a fish, and the reader sees the connection right away to the first story, which deals with an aquarium and the “third country national” in charge of maintaining it. You write about aquariums with such expertise, infusing all the details of caring for fish—and fighting the things that can kill them—with so much metaphorical meaning. Do you keep fish? Did you have to do a lot of research to write this story?

I did keep a tropical aquarium as a child, but I also did a lot of research. The story actually came about because a friend of mine—a journalist—sent me photographs he’d taken at an American military base in Kuwait. One picture was of a fish tank. The other of three men who served the soldiers food. I thought I recognized the men as Sri Lankans and something clicked. I started to wonder who actually took care of that fish tank. One of those three Sri Lankans?…voila.

I admire that you don’t do a lot of “cultural explaining” in these stories—there aren’t passages where you’re writing a primer on Sri Lankan history.

If it looked at all like information—if it smacked at all of a news report—I left it out.

There’s a kind of trust in readers: that they’ll keep up, that they’ll be informed enough to figure out the context. Yet many Americans aren’t familiar with the war in Sri Lanka, or the country in general. How did you decide what factual information to give and what to leave out?

We can find information so easily now, and, yes, I absolutely trust that my readers will look up the war and learn about it on their own.

Handling non-English words can be a political statement for writers. You weave Sinhalese words like idiyappam, malli, raksha, and punchi-amma, seamlessly into the stories. How (or why) did you make the decision not to italicize?

Wow, that’s a good question. I think the choice is personal to the writer, and I don’t judge writers who do italicize foreign words. In a book that seeks, however clumsily, to smudge the boundaries of what constitutes otherness it felt odd to then turn around and italicize some words. Also, there are words that we use in English very naturally that are actually taken almost directly from a foreign language—pajama and dinghy, for example. Italicizing then becomes an exercise in degrees of foreignness.

“Ismail” is one of my favorites—I think it might have been the first story I read of yours, way back in Narrative. Again, it touches on how tensile the bonds of family can be. But what I really want to know is: where on earth did you get the idea for the turkey/milk stink bombs?

Turkey bombs are real! I have a good friend who is a visual artist. He and a fellow artist tried to create turkey bombs as a conceptual art piece. That’s how I discovered all the nitty-gritty details of making one. However, I admit to only theorizing about the concept. I’ve never tried to build one myself. And, no, my friends never successfully created turkey bomb art.

You teach as well as write—does the teaching affect your writing at all? How do you balance the two?

I love teaching. I love writing. I feel grateful to be doing both, and because of that I find ways to balance each. Mainly, I’m grateful because both endeavors keep me unbelievably optimistic about the future of books, of fiction, of the short story. For decades we’ve been declaring the short story dead, but this semester my short story workshop included 17 undergraduates who focused solely on conceiving of and writing their own story collections. What better sign of life can there be?

What are some books you’ve read lately and enjoyed?

What are some books you’ve read lately and enjoyed?

I just finished Bushra Rehman’s Corona and loved it. It’s a novel in stories and focuses on a desi girl growing up in Queens—a subject I have a lot of affinity for. It wonderful captures life in the post-9/11 desi community.

What are you working on now?

I’d like to learn to speak Tamil. I admit to being intimidated because I’m starting from scratch, and I’d need, on a basic level, to learn a different alphabet. That also seems like a good reason to try to learn.

Do you think learning Tamil will change your fiction writing in any way?

I’m not sure. I’m not sure I could become a good enough Tamil speaker. But I want to try and broaden my mind and vocabulary.