Jared Yates Sexton

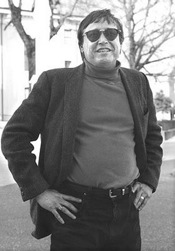

When I met Jared Yates Sexton for the first time at the BULL: Men’s Fiction table in the book fair at AWP last year in Chicago, I felt as if we’d known each other for years. I was immediately comfortable in his presence, like we had shared MFA program war-story experiences or had been drinking buddies or maybe even both. Perhaps it was his casual, down-home swagger, or sleepy grin, or the speed and grace with which he offered a handshake, but after reading his debut collection of short stories An End to All Things (Atticus Books), it hit me that perhaps the old adage “you are what you read” is less true than “you are what you write.”

Sexton’s stories, often centered around blue-collar Midwesterners, are painted with precision and care, with an emphasis on the voices of a what Sexton calls “Recession America.” We recently sat down for an online chat session to talk about the collection, his process, and his background. And though we were separated by a thousand miles of Internet tubes, things still felt quite chummy.

Nick Ostdick: One of the many things I admire about this collection is how cohesive it feels of a piece, while at the same time the individual stories are so varied and diverse, moving from gothic Americana à la Bonnie Jo Campbell to Barry Hannah-esque lyricism and language play. So I’m curious as to how the collection was assembled: piece-meal over a number of years or from start to finish as one unified project?

Jared Yates Sexton: It was pretty much a hulked-together kind of thing. A few of the pieces – “Old” and “Night of The Revolution” – were the last things I wrote while I was completing my MFA. They were kind of remnants of when I was going through a Hannah phase, actually, when I was experimenting and into lyrical strings. Then, when I moved past graduate school I found myself getting really into the idea of minimalism and the “traditional” short story. I’ve found that my work goes in cycles like that. That I start experimenting and then wind my way into simple pieces with an interpersonal relationship and letting the plot and quick declaratives lead the way. But it’s a real ramshackle of a book that gets tied together because it all has to do with the economic realities of “Recession America.”

Speaking of cycles, I was really taken with how you navigated between flash fiction and more traditional-length stories. Do you set out to write with the knowledge that a certain story idea will be more compressed or “flashy,” or is this something you discover along the way?

Within the first paragraph, judging by how much distance the narrative spans in those initial sentences, I have an idea of how much space the piece is going to take up. If I’m spanning minutes between words or days or weeks or years, I know the plane’s going to land in a few pages. If I find myself initially going into scene, smelling, hearing, feeling stimuli, and I want to sit down and have a drink or see how things turn out, I get the feeling that this is going to be a bigger fish.

Is it safe to say you have the ability to adapt your initial drafting process once you get an inkling as to the scope of a story?

That’s been the rub. I can get a short piece, a flash piece, a short short story, out in an hour-and-a-half to two hours. If I like what I’m looking at, I’ll let it breathe for a day and then come back and give it an initial edit. If I still like it, I’ll give it another the next day. That can go on for up to a week or a week-and-a-half. If I don’t like it, I’ll put it in my spare parts folder – or what I like to call “B-Sides” – that can either refigured or re-imagined or reconstituted later. The longer pieces are trickier. Sometimes I’ll blaze through them and get an entire fifteen page draft out and I’ll have the same process as the short pieces. If it’s longer, or if it doesn’t come as easy, I’ll let it breathe for a day and then come back and edit what I’ve got so far. That helps to reacquaint myself with the voice and tone and narrative. Then I’ll keep moving forward.

I have to admit, I’m really taken with what you said a moment ago about “how the plane lands” in terms of moving forward and finding your way toward the ending of that initial draft.

Some might not think it’s an apt metaphor, but when I’m getting ready to close out a story it strikes me that I’m giving birth to the final movement. I’ve taken these characters out for a spin and the things they’ve done and said and thought are going to lead to this new reality that will either be completely different from the one they knew or a slightly changed reflection. For me, I want an ending that feels organic. Some people call it earned, but I say it’s an eventuality that’s going to be realized. The last line, or last lines, should reflect some kind of truth that’s had its groundwork laid over the course of the rest of the story and is now, having been through the narrative, the only way it can come together. Sometimes the result is so easy it makes me walk away believing in collected unconscious. Sometimes it’s so hard it makes me question whether I’m a writer.

You just mentioned the idea of “Recession America” as a thematic arc throughout many of these stories and the collection as a whole, and it’s got me thinking about my time in graduate workshops at SIUC with Pinckney Benedict and what he always referred to as the “allegory of the self,” or this idea that the writer knows where he/she is in the fiction at all times. How much of your own feelings about work, the shrinking middle class, and the current state of the nation are reflected in these stories, be it through characters, theme, setting, etc?

I feel I can’t help but write about work and class and identity. It seems a cliché to think about working class families in the Midwest, or other manufacturing areas, gathering around a meal and laying out their woes or opinions about economy or oppression, but that was the reality of my childhood. I’m the son of factory workers, of poor, working-class parents. The people I associated with, or who I saw as role models, were usually foul-mouthed Midwesterners who boozed and caroused. That heritage, for me, is no different than having a certain color hair. Most of my fiction is either a retelling or restructuring of things from my life. My experiences, my loved ones, my enemies, my opinions find their way into my prose whether I make a concerted effort to include them or not. The reality I know is rife with those things, those situations. The experimental pieces I write, which oftentimes are very outlandish or surreal, are not excerpts from my life but actually logical extensions of the things I believe or fear. It’s absolutely impossible to separate yourself from your writing if you’re doing it right. You should be living and breathing in the sentences, just past the line of sight of the reader. They should be able to feel you there but not be distracted.

I think it’s safe to say we all have one or two barrels worth of material or experiences that we keep exploring, right?

There’s no way around it. An example – the first novel I ever wrote was about a factory worker in Indiana. His life is off the rails. He drinks, he smokes, he womanizes. At the end of the day he’s got his father to blame. In style it’s a gritty piece of realism with pulp undertones. The book I’m working on right now is a sort of dystopic piece that’s trying to dissect nationalism and the growing apathy of the Internet age and personal freedom. But at the heart of it? Class. Son/father dynamics. The idea that experience and class shapes us. I’m sure at some point I’ll talk about a book or a story that doesn’t have any of those themes at the heart, but I can tell you right now that they’ll be lurking somewhere under the surface.

As a teacher of writing, I’m sure you know the standard sage advice of “write what you know” sometimes comes under fire, but can I assume it’s something you attempt to impress upon your students?

That’s probably where young writers should start. I mean, the next collection has a ton of stories that have pieces that have absolutely nothing to do with things that have happened in my life. But they have to do with my general philosophies about existence, good-and-evil, and love. And those philosophies are an extension of what I’ve experienced and gone through. So when young writers starting honing their craft, it’s less about plot, it’s even less about theme, and it’s more about getting well-rounded, believable characters who can move through physical space. Once those fundamentals are in place, and the writer feels good about their craft, that’s when they can start venturing out and experimenting. Then they can start constructing new worlds.

Let’s talk about publishing for a moment. Many of the stories in the collection originally appeared in small, independent publications—magazines of great quality, of course, such as [PANK] and Hobart, but ones that are still under the radar. Your publisher, Atticus Books, is also an indie-lit outfit. Was working primarily with these types of publications something you set out to do, or something that just happened without much intentionality?

I think the answer has to do more with the style of writing I tend to produce. My wheelhouse, as its been over the last couple of years, has either been these short, minimalistic pieces that are kind of like off-beat, strange Carver stories mixed with some Larry Brown or experimental short pieces that sort of challenge the border between good taste and grotesquery. There’s not much of a market for that. Most publications you wouldn’t consider “indie” aren’t interested in those styles at all. They’re looking for middle range to longer stories that are oftentimes more about frames and lyricism. But I’ve managed to find a lot of editors and publishers that appreciate those kind of pieces that I enjoy writing.

I also think the change in the market, the death of the major publishing houses, the downfall of these publication heavyweights – Esquire doesn’t run much fiction anymore, the New Yorker has a special issue every now and then with their hand-picked stable of writers – has led to this sort of scattershot universe where independent presses and publications have had to pick up the slack. I mean, I can’t imagine someone like a Richard Brautigan getting any sort of mainstream attention anymore. Literary fiction is already an antiquated art by many standards and something that challenges even the mainstream idea of literary fiction would probably fall on the ash heap of publishing.

I would imagine then it could be quite tempting to tailor stories for the publications that have been receptive to your work. Has the hunch that a certain story would be a great fit for X or Y Magazine ever influenced your approach to a story?

I think, maybe three or four times, I’ve finished a story and thought, once I finished with the draft, that it would be good for a particular publication. For example, I finished this piece called “Yankee,” which is probably going to end up being the title story for the next collection. I printed it out, read it aloud, and somewhere in the middle I knew it was the kind of thing I should send to a place like Hobart. Usually though, it isn’t really a consideration. And in fact I have a lot of stories, three or four in the book, where I never got a good grasp on a place to publish them. I looked at a piece like “All The Familiar Places” and was very proud of it but never found a home for it. At the end of the day you have to look at this art, this pursuit, and realize it doesn’t make a whole hell of a lot sense sometimes.

So: You’re in the midst of promoting this book, but you’ve also mentioned another collection and a novel. What’s coming up next for you? What’s on the horizon?

The new collection is completely written and it’s just a matter of getting it in fighting shape and in some kind of conducive order. I read all the stories over the last week or so and I noticed that there’s a real manic-depressive swing to it. Some of the stories are about new beginnings and new chances. What it’s like to grow up and move past a hell-raising history. But some are just these strange meditations on nihilism and despair. It’s been an odd year for me, what with the new job and move and with my father dying last April. All of the swings are present and they’re in these stories that, like this collection, span everything from minimalist short stories to straight-up experimental pieces that venture to absurd and grotesque places.

The novel, on the other hand, is a whole different ballgame. It’s an idea I’ve had kicking around my head for a long time now. It’s basically this fascist society where a hyper-nationalistic America is crammed into this gigantic, walled factory and for entertainment the workers watch TV shows where their friends and family are given a few minutes to talk and then killed. More or less, it’s a world where capitalism and fascism and consumer apathy have won the war.

And I have to ask, given that music features largely in many of these stories, but also because you cited the lyricism and musicality of Barry Hannah as an influence, what records or bands are you really digging right now?

And I have to ask, given that music features largely in many of these stories, but also because you cited the lyricism and musicality of Barry Hannah as an influence, what records or bands are you really digging right now?

Oh, it’s a real toss-up depending on the day. On the way into work today I was listening to an album by ELO and cranking up the volume and rolling down the windows. At home I’ve got After The Gold Rush on my record player. The mood and tone of my writing sort of follow those kinds of trends. If I’ve got Darkness On The Edge Of Town in my CD player then I might get some working class heroes with glimpses of hope. If it’s Warren Zevon, I might have a sad sack ordering a call girl to a rundown hotel room. I think we’re all pliable creatures in the long run.

Pliable creatures? I like that.

I have to admit, I’ve never thought of it that way but it’s the goddamn truth.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on the work of Jared Yates Sexton, please visit the author’s Website.

- You can also check out BULL: Men’s Fiction, where Sexton serves as Managing Editor.

- Visit Atticus Books to see the publisher’s catalog of new and forthcoming titles.

- You can also read “A Man Gets Tired” at [PANK].

- Finally, read Jeremiah Chamberlin’s tribute to his former teacher Barry Hannah, following the author’s death in 2010.