Two years ago I drove north from my home in southern Maine to Quebec City in late November to celebrate my partner Tammy’s birthday. We took a room for several nights in a small stone-faced hotel located in the old city between the wide, swift St. Lawrence River and the high, walled upper-city; out our bedroom window, beyond the leafless branches, I could see the spires of the regal Château Frontenac looming above.

The city is quiet in November: summer’s chaos is a distant memory, the leaf-peeping tourists have come and gone, yet the city’s famous winter carnival madness has not yet begun. We walked the old, narrow streets and marveled at the buildings. We ducked into dim bars for red beer and charcuterie boards. We smiled and laughed. In the evenings, we walked more. We walked to digest decadent meals of escargot tossed in bone marrow, duck confit poutine, and maple crème brûlée. Some evenings spit snow and the cobblestones turned slick so we held tight to one another as we shuffled along.

The city is quiet in November: summer’s chaos is a distant memory, the leaf-peeping tourists have come and gone, yet the city’s famous winter carnival madness has not yet begun. We walked the old, narrow streets and marveled at the buildings. We ducked into dim bars for red beer and charcuterie boards. We smiled and laughed. In the evenings, we walked more. We walked to digest decadent meals of escargot tossed in bone marrow, duck confit poutine, and maple crème brûlée. Some evenings spit snow and the cobblestones turned slick so we held tight to one another as we shuffled along.

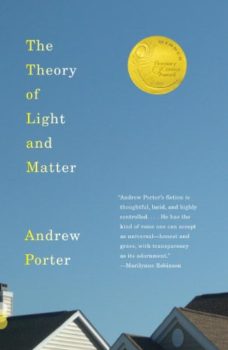

With breakfast, or during the day when we slipped into a café to get out of the wind and warm up with an au lait, I read from Andrew Porter’s calm, searching debut collection The Theory of Light & Matter (University of Georgia Press, 2008), winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award.

One afternoon we drove a few miles north of the Quebec City, past the frozen Montmorency Falls, and across the steel suspension bridge to the Île d’Orléans in the middle of the St. Lawrence River. The roads were empty for mile after mile on the ring road around the island and the wind whipped snow off the fields. The sloping rural landscape along the shore made me think of Prince Edward Island—further north and east of Quebec—where my grandparents took my brother and me as children to stay on a dairy and potato farm. Those summer trips were idyllic, and as such belied the turbulence and chaos my brother and I attempted to navigate back home. Driving slowly around the frozen landscape of Île d’Orléans I began to think about Porter’s story of brothers, “River Dog,” and its evocative opening line: “It is easy now, after everything that has happened to my brother, to say I didn’t hate him.”

Porter’s first-person stories are unhurried with long stretches of exposition; even when they wander seemingly without plot they remain restrained and captivating. The narrator of “River Dog” reflects on teenage years and his complicated relationship with his older brother, Doug. In particular, he struggles to re-assemble in his mind a high school party and whether or not his brother sexually assaulted a drunken girl. The narrator’s voice is earnest and haunted:

“The first time I actually heard the story about Carrie Huber was from Trey, who told it like a joke…. Later, there were other versions of the story. Versions I heard at parties that summer. In on version Doug and Trey lead Carrie up into the hills behind the Bensons’ and hold her down against a large rock, leaving bruises on her tailbone the next day.”

He thinks about a series of earlier incidents with his brother—strange trips to the dump near their childhood home, scary behavior along the shores of the muddy Pequea River—and as he can’t help but view each of these memories through the obscured lens of rumor and time. The narrator is unnerved by his inability to know his brother; his voice grows searching, even fragile, at times. In the end, he seems startled that nothing comes of the incident with his brother:

“Everything you would expect to happen afterward didn’t. There were no phone calls made, no talk of Carrie Huber pressing charges or getting the police involved. Nothing like that.”

While the specifics of the situations of “River Dog” bear no resemblance to my life, it is a story about the electricity that exists between younger and older brothers, a story about the hurtful confusion of not understanding those closest to you, and those are things I know well.

When I was a freshman in high school, my older brother should have been a senior in the same school. I was not looking forward to this. I was a socially awkward skateboarder turned inward by my stepfather’s mocking abuse; my brother was gregariously, stylish, and becoming a soccer and volleyball star. As Porter’s narrator says:

“…it seemed my brother had ruined whatever social potential I once believe I had. He made it impossible for me to be anything more than what I was already, which was invisible.”

But suddenly, the summer before my freshman year, my brother moved to California. He lived with our cousin and became a starter on the varsity volleyball team, coached by a recent Olympic gold medalist. After a few years, hours of beach volleyball, and working in an athletic shop, my brother began modeling volleyball apparel for catalogs. Seemingly overnight he signed with an agency and was flown to Milan for runway work. The next thing I knew I couldn’t open Esquire or GQ or Rolling Stone without finding him there—the brother I shared a bedroom with from birth to age 15—looking back at me from the pages in black-and-white Giorgio Armani ads. His life had become more of a mystery to me than ever before.

After my brother escaped to California, my home life in Maine decayed to depths neither of us could have imagined. My stepfather left, only to be replaced by my mother’s equally regnant new boyfriend. I stayed out of the house, skateboarding as long I could, then holed up in my room with books. I felt abandoned by my brother; I was hurt, maybe even angry. It took me years to escape the way he had, and my departure was, to say the least, messier. My brother never returned to California after that first trip to Milan, and he has lived there for more than twenty years now—I once feared bumping into him in the high school hallway, but the reality became that we have never lived on the same continent as adults.

These days, I see my brother fairly regularly but there were stretches when I didn’t see him for years at a time, this man who knows my youthful secrets and scars better than anyone else on the planet. Sometimes he comes home to Maine and in his big brother way stirs things in me I would prefer remain unstirred. My brother is the only person I have ever punched in the face; we were adults when this happened and I am not proud of it but he can touch a deep, small place within me and in that moment punching felt like the only way to communicate with him—maybe this is how, in our confused way, brothers sometimes articulate our confused love: nagging, poking, punching.

Driving around the snowy, windy Île d’Orléans I thought about my brother, about the complexity of our shared childhood and our individual pursuits to become better men. My mind tends to wander when I travel, as though all the memories that are held at bay by day-to-day life become rattled by the disruption of routine and suddenly come pouring over the transom. That day on the little farm-covered island in the middle of the St. Lawrence River, Porter’s “River Dog” reminded me how mystified I am by brotherhood, how siblings can become strangers to one another, and how people we shared bedrooms with, survived childhood with, can become in many ways unknown to us in adulthood.

During May of 2016, Joshua Bodwell celebrated National Short Story Month by selecting one short story each day and writing a micro-essay that attempted to contextualize how the story fit into his reading life and the lasting impact the story had made on him. He posted the essays on Facebook each day.

In the end, he wrote nearly 18,000-words about thirty-one different stories by thirty-one different authors. A version of this essay on Andrew Porter’s “River Dog” appeared as the nineteenth installment of that thirty-one day project.