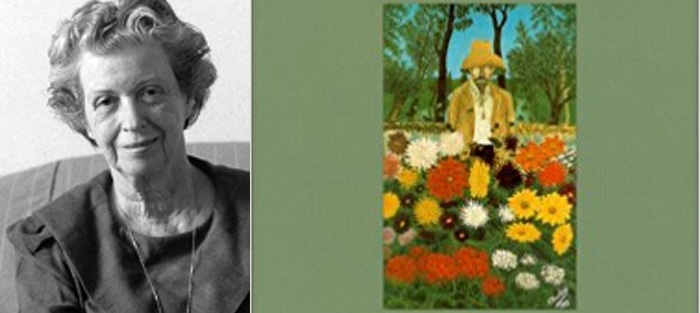

Josephine Jacobsen lived not far from me in Maryland, but I met her late, through her 2003 obituary. She died on the cusp of her ninety-fifth birthday. Over the course of a distinguished career, she produced ten volumes of poetry, four collections of short stories, and essays and criticism as well. Jacobsen served from 1971 to 1973 as Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress (the office now called Poet Laureate). She received the Poetry of Association of America’s Robert Frost Medal for Lifetime Achievement, among many honors. Publishing her first poem in 1920, at age eleven, she wrote continuously, producing some of her finest work in her sixties, seventies, and eighties. Learning about Jacobsen was timely and inspiring for me. When she died, I had recently begun writing fiction again after many years’ hiatus.

How had I missed her? Intrigued by her obituary, regretting my tardiness, I immediately read her penultimate collection of poems (In the Crevice of Time, Johns Hopkins, 1995) and her collected stories (What Goes without Saying, Johns Hopkins, 1996). What should go without saying is that Josephine Jacobsen is a great American voice of twentieth-century letters. She should need no introduction. However, if like me you’re late to make her acquaintance, let me present Josephine Jacobsen through her story “The Edge of the Sea.” Go on and read her, let her speak for herself. And watch and listen to her (thanks to the time travel magic of the internet) converse with poet Roland Flint in 1995. Admire her elegance in a pale pink suit that almost seems to require white gloves as accessory. She looks, from head to toe, the wife of a tea importer, as she was.

How had I missed her? Intrigued by her obituary, regretting my tardiness, I immediately read her penultimate collection of poems (In the Crevice of Time, Johns Hopkins, 1995) and her collected stories (What Goes without Saying, Johns Hopkins, 1996). What should go without saying is that Josephine Jacobsen is a great American voice of twentieth-century letters. She should need no introduction. However, if like me you’re late to make her acquaintance, let me present Josephine Jacobsen through her story “The Edge of the Sea.” Go on and read her, let her speak for herself. And watch and listen to her (thanks to the time travel magic of the internet) converse with poet Roland Flint in 1995. Admire her elegance in a pale pink suit that almost seems to require white gloves as accessory. She looks, from head to toe, the wife of a tea importer, as she was.

But appearances can be deceiving. Think of Emily Dickinson and that infamous white dress. Jacobsen is fierce, bold, and frank—in her writing, and about writing. Interviewed by The Baltimore Sun in 1997, she described seeing her first poem in print. Eleven years old, she “stood on the sidewalk, obstructive, stunned, looking at my words, naked, displayed to the world and happily I did not know that this deflowering would be a climax never reached again. For I was purely satisfied.”

So, forget the polite white gloves. The gloves that fit Jacobsen are the fabled velvet ones disguising steel hands, or custom-tailored boxing gloves. “The Edge of the Sea” packs a punch: a one-two-three punch, with deft and subtle set-up, elegant and lethal delivery. This story knocked me out the first time; with each reading it happens again even though I know what’s coming. Re-reading, I try to be alert to how she does it. (Remember Emily Dickinson’s line about splitting the lark to find the music?) The clues are hiding in plain sight, all the bread crumbs scattered. However, knowing what’s coming doesn’t blunt the shock. I love this story, every time, for its language, characters, and action. I love this story because it’s haunting, and hauntingly well-wrought: simple and plain on the surface, complex and deep underneath. I love it because every time I read it, I dive deeper and come up gasping.

Speaking of diving, this story is set on the edge of the sea, and water infuses every page. The events are narrated by twenty-year old Caddy, recounting the final day of a vacation intended to help her recover from “a sort of illness.” An old family friend, Mrs. Brounlow, had suggested Caddy’s trip, travelling companions, and destination: “‘Acapulco,’ said Mrs. Brounlow over her teapot, ‘is a disaster. But it is perhaps the most beautiful site in the world, and the sun never stops shining.’”

The vacationing quartet comprises Caddy, her second cousin Dan, his wife Lily, and Lily’s half-sister Gina. Awed by her slightly older companions, particularly Dan who “affects people as sunshine does in winter,” she’s flattered to be among “three so beautiful as to embarrass her . . . like one of those shameless advertisements in thirteen colors that invite either to sun, or sand, or sea, or to all three. But instead, she knows that they are simply beautiful, and good, beloved, and loving.”

The story is five pages long. With dramatic poetic economy and precision, Jacobsen presents the story’s world and cast of players, sets it in motion, and wraps it up. With spare, sensory language Jacobsen paints an idyllic scene, intimates underlying threat implicit in the beauty, and finally peels back the lustrous surface to reveal darkness and damage. Words, images, and phrases repeat: sea, sun, tide, moon, sand, water, waves, light. The repetition works like refrains in poetry and music—and like the lulling and disturbing sound of the sea. The voice of the sea is the initial voice of the story: “They can hear the sea in the darkness near them . . . it turns out to be breathing there, with a soft rush and a brief silence, and another soft rush. It is quite near.”

Caddy, and her enchanting companions, are at the edge of something powerful and mysterious.

There is the edge of the sea, Caddy thinks, and there is the foam at the false edge. There is the invisible sand on which one walks out into the salt water; this is land, covered by the nets of the sea, the celestial chicken wire of light. But at a shifting moment, just somewhere the foot cannot find the sand below, and the edge is crossed, the sea’s edge, into the sea’s power.

The edge is the territory of this story, literally and metaphorically. The day’s events take place on the edge of the Acapulco bay; Caddy is unknowingly balanced on the edge between illusion and discovery. Acapulco, as Mrs. Brounlow had foretold at the beginning, proves a beautiful disaster. The concluding event there is indeed disastrous. But Jacobsen saves the climactic final revelation for later, back in Mrs. Brounlow’s parlor. She delivers the final blow with stunning, stealthy sleight of hand back, revealing the scope and scale of the disaster.

This is a rip-tide of a story. Josephine Jacobsen would say don’t over-study her technique. Rather, enjoy it. Let the wave of story sweep you away. Dive in again, re-read “The Edge of the Sea” and then read more. Jacobsen’s work is all about the mystery of balance and falling. Danger. Precipices. Edges.