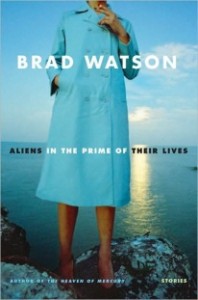

Last fall I was lucky enough to be sitting in Barry Hannah’s fiction workshop at Ole Miss, which would turn out to be the final class he taught. During a discussion about genre fiction, specifically vampire novels, Barry said, “Let’s face it. The living are just a rare species of the dead.” After reading Brad Watson’s new book, Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives (W.W. Norton, 2010), I am convinced that the author (who studied with Barry at Alabama) subscribes to this same theory. There are no zombies or vampires in this collection, but there are plenty of folks who act like they’re either dead or from another planet. And, yes, many of Watson’s characters are “aliens”—not green creatures with large heads, but alienated, isolated, people who wander through life without an anchor, who don’t feel the pull of gravity.

Last fall I was lucky enough to be sitting in Barry Hannah’s fiction workshop at Ole Miss, which would turn out to be the final class he taught. During a discussion about genre fiction, specifically vampire novels, Barry said, “Let’s face it. The living are just a rare species of the dead.” After reading Brad Watson’s new book, Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives (W.W. Norton, 2010), I am convinced that the author (who studied with Barry at Alabama) subscribes to this same theory. There are no zombies or vampires in this collection, but there are plenty of folks who act like they’re either dead or from another planet. And, yes, many of Watson’s characters are “aliens”—not green creatures with large heads, but alienated, isolated, people who wander through life without an anchor, who don’t feel the pull of gravity.

Watson questions the customary boundaries between sanity and madness, community and isolation. He creates worlds that are strangely distorted, in which dreams and reality are blurred. For example, in the title novella, two teenagers from East Mississippi elope to a town not far from where they grew up. There, they move into a dingy apartment next to a mental hospital. But other than this oddity, and a singular occurrence (Will returns home to find two hospital patients in his living room, and they share a strange conversation about the child he and his girlfriend, Olivia, are expecting) life seems fairly normal at first. Will finds good work as a carpenter. Olivia takes well to motherhood after the birth of their son, Leo. They are happy.

Yet soon enough, the stability of their lives begins to shift. An old teacher of Will’s from grade school shows up on their porch, and the reader discovers that Will’s happiness—his whole life, in fact—is an illusion. Not just metaphorically, but literally. In the subsequent paragraph we are yanked back in time to when Olivia is still pregnant and about to give birth. The doctor is telling Will that his perceived life has been a dream; stranger still, the doctor even recapitulates the dream. From here, the descent is quick and sudden: the child is given up for adoption, Olivia’s parents take her away to live with out-of-state relatives, and Will finds himself alone. As his life further unravels—at one point he’s admitted to the same hospital they once lived next to—he struggles to remember his wife and child, pondering what might have been if things could have turned out like they had in his dream.

Brad Watson / Photo by Lindsay Beamish

Though it might seem like a spoiler to give away such a dramatic plot twist here, what’s most interesting to Watson and to us as readers is not the delusion itself but how we all craft and shape different versions of ourselves and reality. Watson’s narrators are unreliable, their memories often foggy. They either cannot or will not create meaningful bonds with others. Some have always lived on the fringes and never had a chance to be happy. Some lose their way as they grow older, then look back at their youth with angst and regret. Regardless of circumstance, however, nearly all of them have somehow detached from the world—sometimes because of alarming outside forces or traumatic events, other times because of self-delusions. Yet we follow them because, for the most part, they feel like real people, people with whom we can strangely empathize, despite the fact their problems are usually much vaster in scope than our own. This is part of Watson’s design—to create disturbingly real characters who the reader is nevertheless surprisingly moved by.

In “Water Dog God,” the narrator, an older man, finds that a young girl named Maeve has wandered into his yard after a tornado, following the stray dogs onto his property. We learn that a pregnant Maeve has fled from her abusive and incestuous father. “Not even seventeen and small, but she looked old somehow. She’d seen so very little of the world, and what she’d seen was scarcely human.” The old man tries to give his own life meaning and purpose by caring for the girl—he feeds and bathes her and tries to protect her. Though she remains distant and unresponsive, the girl stays and doesn’t run off. So we empathize with both characters as they try to rehabilitate their lives and each other.

Imagination also functions not just as a tool for delusion, but for getting at the unseen. “Fallen Nellie” concerns a woman found dead on a beach. Though only in her thirties or forties, she wears a skimpy bikini that shows her weather-worn skin. The narrator imagines how this woman got to this point, briefly sketching the possible arc of her life: a daring girl going wild with boys, booze and drugs, leaving home for the gulf coast, living with her boyfriend who later moves out, surviving a hurricane, and then finding herself getting older, trying to recapture her youth with a variety of men. It’s only seven pages, but by the end I had a vivid and accurate image of her.

Watson’s use of a third person subjective point of view in many of these stories allows him to shift the narrative distance so that we feel intimate with the psychology of his characters while retaining the objectivity necessary to understand what they are unable to about their lives. By moving fluidly from what his narrators see or think to a broad panoramic view of their situation, he not only achieves this important sense of perspective but also harnesses the language needed to elicit our sympathy for these characters. Consider the end of “Fallen Nellie,” as he describes the final years of the dead woman’s life:

At twenty-four she could feel herself aging in increments as small but distinct as the ticks of a clock. She could feel the fluid swirl in each tiny cell, microscopic planets bound by a body, an infinitesimal universe speeding away from all others. She had a vision of this and was stricken with fear that woke her at two, three in the morning parched and dizzy. She grasped at others to decrease her speed… and at this speed they had no faces, no names. In this manner she tumbled through time all the way to the very end of it. Doesn’t matter which one did it to her…it was done.

The obvious danger, of course, when writing about characters we would describe as “grotesques” (to borrow a term from Sherwood Anderson) due to either the calamities of their situations or their interior lives, is that of caricature. Watson occasionally distorts his characters so that they become “types” more than individuals. In “Vacuum,” Watson’s narrators are three young brothers, unnamed and close in age so that they blend into one collective voice. The author describes them like a pack of young dogs:

The boys were sitting there and staring at her as if they were not only mute but deaf, or like dogs being spoken to and unsure of what the tone of the person’s words meant, that clap-mouthed momentary attentive interim between daydreaming and the next distraction.

Similarly, his characters are sometimes so sad and ineffectual that they risk failing to elicit the reader’s sympathy. After all, it’s sometimes difficult to muster emotions for intelligent people who are well aware of their depression or emotional problems, yet who seem content to wallow in their own despair. Loomis, the narrator in “Visitation,” is a gloomy pessimist separated from his wife. He has seen therapists and taken pills, but long ago he stopped fighting and has accepted that his life and his nature are hopeless. He flies to California to visit his son, but once there, Loomis makes little effort to engage or bond with him. And, as such, his struggle might have the tendency to be dismissed. Especially in comparison to the other characters in this collection who do have disproportionate struggles in their lives.

Yet Watson’s skill as an author is to create characters who walk that razor-thin line between eliciting our compassion or our dismissal. For example, as Loomis drinks his second beer at a crowded restaurant near a southern California beach, the author writes:

…he felt indicted by all the other people in this teeming place: by the parents and their smug happiness, by the old surfer dudes who had the courage of their lack of conviction, and by the young lovers, who were convinced they’d never be part of either of these groups, not the obnoxious parents, not the grizzled losers clinging to their youth like tough, crusty barnacles.

Likewise, we find that we had been judging Loomis. Further, it provokes us to ask: “How would I judge these same people, and how would they judge me?”

Again, this is part of the overall theme of isolation and alienation that permeates the book: judgment and being judged separate us from one another, as well as ourselves. Likewise, by setting most of the stories in the Baptist Belt of eastern Mississippi (Watson himself is a Meridian native), as well as in the South of the 1960s and 1970s—not the “Old South” of Faulkner, but old enough that the cultural and regional differences were still quite large—Watson heightens our awareness of the ideas of “belonging” and “difference.” In this way, geography and history lend themselves well to his work by allowing him to not only bring together those displaced people whose secrets—and secret, interior lives—are revealed through the collision of small encounters and random events, but also to help him illuminate how time and place shape us.

Near the end of “Visitation,” Loomis and his son encounter a woman outside their motel room. She tells them to “watch out for gypsies.” When his son asks what gypsies are, Loomis explains that they are wandering people known for stealing children. Later, when Loomis is alone, he sees the woman again and asks if she’s a gypsy herself. She says no, but she can read his future. After examining Loomis’s palm, she flatly calls him a “creature of disappointment.” By the end it’s clear that Loomis is the true gypsy, wandering though his middle years, trying to steal back his son.

Near the end of “Visitation,” Loomis and his son encounter a woman outside their motel room. She tells them to “watch out for gypsies.” When his son asks what gypsies are, Loomis explains that they are wandering people known for stealing children. Later, when Loomis is alone, he sees the woman again and asks if she’s a gypsy herself. She says no, but she can read his future. After examining Loomis’s palm, she flatly calls him a “creature of disappointment.” By the end it’s clear that Loomis is the true gypsy, wandering though his middle years, trying to steal back his son.

At times I asked myself, how human are these characters? Are they alive, or are they perhaps dead spirits wandering in search of their past lives? Whatever the answer, and despite their often hopeless plights, I cared about these characters and was moved by them. I attribute this to Watson’s great skill as a writer; his voice in each of theirs carried me seamlessly through this collection.

Further Links and Resources

– Preview Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives and read excerpts from the collection on the publisher’s website.

– Read the story “Visitation” (from Aliens) in the New Yorker, where it was published in 2009.

– Learn more about the author’s previous books, the novel The Heaven of Mercury (2002) and the story collection Last Days of the Dog Men (1996).

– Look for an interview with Brad Watson later this week on Fiction Writers Review!