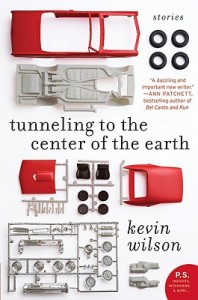

If Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (HarperPerennial, 2009) were a child, it would be the kind who held your hand until you reached the road and then insisted—slapping at your grasping fingers without taking his eyes off the road—on crossing the street without help. If Kevin Wilson’s debut collection were a car, it would be the kind of bubble-topped, shark-finned future-car that you see on footage of old World’s Fairs, but you would see it out in the world, cruising the miracle mile. If this book were a friend, it would be the kind who goes with you to the bar and doodles on napkins all night while everyone pounds beers and then, when everyone has forgotten about her, comes out with a one-liner that brings the house down.

If Tunneling to the Center of the Earth (HarperPerennial, 2009) were a child, it would be the kind who held your hand until you reached the road and then insisted—slapping at your grasping fingers without taking his eyes off the road—on crossing the street without help. If Kevin Wilson’s debut collection were a car, it would be the kind of bubble-topped, shark-finned future-car that you see on footage of old World’s Fairs, but you would see it out in the world, cruising the miracle mile. If this book were a friend, it would be the kind who goes with you to the bar and doodles on napkins all night while everyone pounds beers and then, when everyone has forgotten about her, comes out with a one-liner that brings the house down.

Do you want to read the book yet?

Because I’m trying to make you want to read it.

Kevin Wilson, who also helps run the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, has put together a strong and surprising collection of wonderfully odd stories. We encounter an old woman who works as a substitute grandmother for children whose real grandmothers have died, or gone senile, or have had a falling out with the real parents. We follow a young man who, in addition to working in a Scrabble factory—trolling all day through hills of letters to find those he has been assigned—also might have a genetic predisposition to spontaneous human combustion. There is a second-person story, and another in the form of a handbook or lexicon. Clearly, Wilson is interested in the formal possibilities of the short story. But unlike many authors with similar interests, Wilson never abandons the very human and tender hearts of his stories or their characters.

For example, in “The Choir Director Affair (The Baby’s Teeth),” [also anthologized in New Stories from the South 2005] we don’t just hear about the baby with the shockingly large and well-formed teeth; Wilson goes to great lengths to show us the baby’s mannerisms, the general and specific gestures that make it impossible for those who encounter it (including us) not to love it, at least a little bit. We feel the heft of the baby’s small but solid form, the competing clean and sour smells of its body. This is not just a metaphor, Wilson insists, and his intelligence and voice go a long way to making us agree.

In addition to startling story concepts and pleasurably alarming imagery, Wilson also makes the collection work as a whole. Two-thirds of the way into the book, we arrive at perhaps Wilson’s best story. By this time, readers might think we have the author’s number—a little bit of Saunders, with some Bender/Millhauserian weirdness thrown in. Then Wilson hits us with “Go, Fight, Win,” something more in line with Flannery O’Connor and Allan Gurganus. There is always a danger when writing weird, ambitious, surreal-ish short stories in getting stuck in that rut where everything has to be audacious or silly, conceptually. One can imagine another, less full Wilson collection that never would have left this land of Barthelmeian wonder and humor. And that might have been great, too.

Kevin Wilson

But what strikes me as a writer after reading all those more conceptual pieces is how fully realized the domestic “Go, Fight, Win” is. It’s a coming-of-age story about an adolescent girl interacting with her younger neighbor, a boy with some hard to define mental or emotional problems. There are grace notes throughout—pitch-perfect scenes regarding first kisses, investigating the dubious authority that teenagers exert over one another, documenting moments of honest obsession and unexpected kindness.

After “Go, Fight, Win,” Wilson gives us “The Museum of Whatnot,” which encapsulates, in its imagery and concept, the argument for this author’s modes of perception and narrative, like Lorrie Moore’s “How to Be a Writer” from Self-Help or Etgar Keret’s “A Thought in the Shape of a Story” from The Nimrod Flipout. In Wilson’s story, the main character is left to tend a seemingly random collection of bric-a-bracs, to guide visitors through a collection she does not quite understand, that has accumulated randomly and without specific purpose. And in this place, people move, think, feel. They search for meaning, for love. Their lives matter to them, and they matter to us, despite the strange surroundings and odd ornamentation. It is a beautiful story, quiet and subtle and lovely, and it is also a smart story in a really, really smart collection.

So are you going to read this book or what?

Read some of Wilson’s stories online:

- “The Museum of Whatnot” in Fifty-Two Stories (also appears in Tunneling…)

- “The Dead Sister Handbook: “A Guide for Sensitive Boys” in DIAGRAM

- “Hammer” in Waccamaw

- “My Hand, Dead Tissue Severed at the Wrist” in Hobart

- “The Neck’s What Keeps Heart and Head Together” in Blackbird