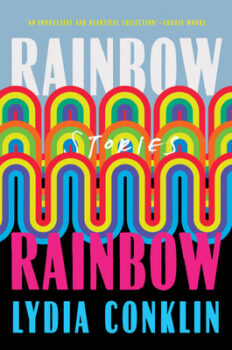

Indu Sundaresan’s fourth book and first story collection, In the Convent of Little Flowers (Simon & Schuster, 2008), contains India’s multitudes, all in relationships of opposition – men vs. women, traditional vs. new, haves vs. have-nots. Throughout, Sundaresan cultivates empathy for her characters and their individual anguish at straddling those great divides.

Indu Sundaresan’s fourth book and first story collection, In the Convent of Little Flowers (Simon & Schuster, 2008), contains India’s multitudes, all in relationships of opposition – men vs. women, traditional vs. new, haves vs. have-nots. Throughout, Sundaresan cultivates empathy for her characters and their individual anguish at straddling those great divides.

The opening story, “Shelter of Rain,” is the sole tale set outside India. A young woman, adopted by Americans as a little girl from a convent orphanage, receives a letter that her mother – whom she has never met – is dying. “Shelter of Rain” sets the tone for the dual forces at play throughout the book’s nine stories. Sundaresan describes a rural family caught off guard by the cacophonous, harsh city; parents betrayed by abusive children; an elderly couple forced to live out their days alone, neglected by the many offspring for whom they sacrificed everything.

In the Convent of Little Flowers has a strong undercurrent of outrage against injustice, but Sundaresan manages to steer clear of moralizing by focusing on the complexity of individual motivation. Her characters often buck tradition, in spite of the psychological hold of ancient rites like Sati – when a widow commits suicide by hurling herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. In “The Faithful Wife” a young man’s grandmother begs him to return because there is to be a Sati of a child-widow. The man, a journalist named Ram, cannot tell if his elder wants him to prevent the death or simply report it. He considers, “Until this one took place, until it was reported in all its horror to the country, people would not choose to condemn it. Ram knows too that the mere suggestion of a tragedy is never as powerful as the fact of it.” The right path isn’t always clear to Sundaresan’s protagonists, or to her reader.

All the stories but one – a kind of sci-fi reincarnation fable – deal with the most intimate family relationships: child and parent, husband and wife, sister and siblings. Sundaresan thrives in the silences and histories, intimacies and betrayals of families. In “Hunger,” a middle-aged woman named Nitu, trapped in an unloving marriage, observes the youth of Mumbai at a dance club:

There is a hunger in them. A bare-naked hunger on the edge of starvation. It is so stark, it is embarrassing. A hunger that makes them forget etiquette and rules, and in doing so, makes them mesmerizing to me.

Transformation hovers just beyond her reach, and the proximity of old and new, glittering wealth and abject poverty, license and tradition gives Nitu – and Sundaresan’s other creations – the real possibility of choice.

Throughout In the Convent of Little Flowers, dissatisfaction drives rebellion against societal constraints. Breaking free results in both healing and heartache – a grandfather might reconcile with his illegitimate grandson, but an abominable son might just as easily drive his parents to a desperate act. Yet even in Sundaresan’s darker endings, hope glimmers, sometimes through a companion in suffering. Describing life with her domineering husband, Nitu justifies staying with him: “Because there is no other way. Because this is all I have, or so I have been taught. In the end, it comes down to this.” In a few short pages the full weight of her life, and all the indignity and repression she endures, has fallen upon the reader. Thus, it is a great relief that she undermines this resignation with the thought, “But it no longer seems enough.” Sundaresan’s powerful writing compels empathy, and in doing so provides a living portrait of India, in all its diversity, through her unforgettable characters.

Further Resources

– In this essay for Powell’s, Sundaresan talks about becoming a writer. And here are two interviews with the author, one from 2009 on BlogCritics, and one from 2007 in the California Literary Review.

– You can read this excerpt (one complete story) from In the Convent of Little Flowers on Simon & Schuster’s website.

– Sundaresan’s three previous books were all novels. For in-depth descriptions of each, click on the titles. In brief:

The Twentieth Wife (2003) is is about the Mughal empress Mehrunnisa. Read an excerpt on the publisher’s website.

The Feast of Roses (2004) is the sequel to The Twentieth Wife. Read an excerpt on Google Books.

The Splendor of Silence (2007) is described by Publisher’s Weekly as “a sprawling story of forbidden love set against the backdrop of WWII and the struggle for Indian independence.” Read an excerpt on S&S’s website.