I have spent the past year pondering the future of the short story. I began my writing career at a time when short story writers were told, continuously, that the short story was dying, and I am, very possibly, simply conditioned to a constant worrying about the form, especially given my deep love for it. I also admit to being thrown by the announcement that two pioneering and influential literary magazines, Glimmer Train and Tin House, were closing shop. Both magazines, in many ways, shaped my contemporary view of the short story and both, certainly, influenced its trajectory and its contemporary iteration.

I recognize that my concern seems entirely misplaced. The short story appears, in that contemporary iteration mentioned above, to be not only as healthy as ever but also a platform for real formal innovation as demonstrated by the work, most recently, of writers such as Jamel Brinkley, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, and Carmen Maria Machado. These writers have used the short story collection as a means of creating and entering deep conversations important to contemporary culture: issues around race, the representation and misrepresentation of the male and female body, queerness. And, yet, I do sense, just beyond my ken, a hazy impression of something passing, and I wonder what it is I am really mourning.

I recognize that my concern seems entirely misplaced. The short story appears, in that contemporary iteration mentioned above, to be not only as healthy as ever but also a platform for real formal innovation as demonstrated by the work, most recently, of writers such as Jamel Brinkley, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, and Carmen Maria Machado. These writers have used the short story collection as a means of creating and entering deep conversations important to contemporary culture: issues around race, the representation and misrepresentation of the male and female body, queerness. And, yet, I do sense, just beyond my ken, a hazy impression of something passing, and I wonder what it is I am really mourning.

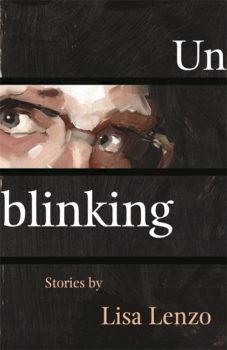

Maybe that’s why every time I try to find the right word for Lisa Lenzo’s latest collection, Unblinking (Wayne State University Press), I keep returning to the word elegy. That isn’t to assert that the collection is particularly mournful or sad or to insinuate anything about Lenzo’s career. The stories are vital and energetic and they fiercely tackle race, class, masculinity. But the realist lens through which they examine the world harkens back a few decades to Carver and Updike and the resulting sensation is to give the stories the feeling of, ultimately, being frozen—stopped in time.

Part of this is due to the fact that Lenzo, as with her previous two collections, roots the setting of Unblinking in Detroit, a city that holds a peculiar, and singular, place in the American psyche. It is, in our imaginations, a city perpetually in decline, riven by its racial history and by poverty. The stories also revisit characters from Lenzo’s previous collection—including Thomas, the angel, and Annie Zito and her family. Many of Lenzo’s recurring characters have aged considerably over the two-decade span in which her collections have appeared and, yet, like the city itself have not been on many levels able to progress.

In the title story, for example, the elderly protagonist Rosie Vito, a reccurring character in Lenzo’s collections, attempts to take her ailing and wheelchair-bound husband, Ralph, to the grocery store. On the way, she finds that Ralph is not properly secured and that she isn’t strong enough to keep him from slipping from the wheelchair on to the ground. She is first forced to ask a homeless man to help them—a man that her husband, who suffers from dementia, mistakes for their son. Later a group of African American men agree, reluctantly, to walk the pair back to their apartment. The men are aware that the white couple, particularly the protagonist, are afraid of them and the white protagonist is deeply aware, and ashamed, of her own racism. The ending, sensitively handled by Lenzo, involves a shared and, illusory, moment of communal witness.

In the story “Spin,” Annie Vito accuses a homeless man, unjustly it turns out, of stealing from her. The story ends with the Annie continuing with her evening after she recognizes her mistake, even at one point laughing at a story involving another homeless man, only to be visited in the final lines by a fleeting vision of the truth of what she’s done. The final set of stories in the collection revisits Annie and her parents repeatedly. The intricate network of support necessary to care for Annie’s dying father maps out the ways race and class intersect at society’s most vulnerable moments and the ways we refuse to fully acknowledge the basic truths of this.

Misperception and revisioning are at the heart of Lenzo’s work. The paraplegic protagonist of “Up in the Air,” probably the finest story of the collection, relishes the moments when he is sitting at tables because when seen from only the waist up he appears strong and muscular. A blues musician well-known enough to draw crowds at local clubs and the attention of local reporters, the protagonist is surprisingly, and movingly, ambivalent about his life and his disability—the result of a fall from a tree. His wife mistakes his ambivalence for a lack of love and desire. It’s only as the story unfolds that the reader comes to realize that the protagonist’s disconnection doesn’t stem from his injuries or a lack of desire for his wife but from the fact that nothing in his life since has matched the beauty of his fall or the moment before he hit the ground.

In fact, Lenzo’s spare prose and even-handed realism are often revelatory. The only misstep in the collection is the story “Losing It.” This story features Thomas, the angel from Lenzo’s first collection, Within the Lighted City (University of Iowa Press, 1997). It’s hard for me to understand the point of Thomas, except as potentially an inside joke about why an angel would visit Detroit. But the premise also doesn’t allow for the intense focus, and the slow revealing of layers of illusion and disillusion, that her other stories offer.

Reading—and rereading—Lisa Lenzo’s work, I realized what I’m sensing disappearing from the American literary landscape. I rarely these days find solid short stories, rendered in the American realist tradition, that take on smallness of life, the moments we barely perceive and yet we know have meaning. It’s rarer I feel to see a work that returns, gently, to people who have not truly grown and evolved but still provide them the grace of nuance while acknowledging their flaws. I hope that I’m wrong and that Unblinking isn’t a eulogy for a fading literary mode but the harbinger of a return.