The characters in Catherine Lacey’s short story collection, Certain American States, reveal many dark or humiliating or contradictory impulses that people rarely want to admit to. In “Violations,” a writer’s ex-husband desperately wants her not to write about him, but feels “an even stronger desire for her to write about him constantly…to feel his absence so profoundly that she was forced—like a child—to pathetically create a simulacrum”; the narrator of “Small Differences” admits to getting pleasure from hearing a friend describe getting dumped and knowing he has “finally been broken.” Though some of the scenarios she plays with stray from realism—the narrator of “The Grand Claremont Hotel” ends up living in ever more luxurious rooms on ever higher floors due to a series of clerical errors—she pays scrupulous attention to the way human psyches and emotions really work.

In addition to this collection, Lacey is the author of three novels: Nobody Is Ever Missing, The Answers, and Pew (forthcoming in July). She’s recently published work in The New Yorker, Harper’s, and The Believer.

I had the good fortune of being able to interview the author in person, sitting at a table in a small classroom, after attending her reading from Certain American States and her craft lecture at the University of Michigan in February.

Interview:

Danielle LaVaque-Manty: In the epigraph to Certain American States, one character asks another if he ever wonders how many times his life is going to end and start over, such that what happened in the past feels like it wasn’t even real. When I read that, I thought it could have also been the epigraph for both of your novels. Your fiction contains a lot of pretty drastic cases of cutting oneself off from the past and starting over. And then in the stories, there is a lot of leaving but there are also incidents of being left. In “Because You Have To,” for example, the narrator moves to a new home with a man who takes off while supposedly just going out to the truck to bring in his last box, and in the title story in Certain American States, a sixteen-year-old is abandoned by the man who raised her. What is it about that scenario—the abrupt and complete departure, and starting over—that interests you?

Catherine Lacey: I feel like it’s a good place to begin a piece of fiction, only insomuch as I think you can learn a lot about presence in absence, and you can learn a lot about togetherness in separateness. In some ways, I think that the whole project of fiction is that you’re asking somebody to leave themselves and be somebody else in this fictive space.

Catherine Lacey: I feel like it’s a good place to begin a piece of fiction, only insomuch as I think you can learn a lot about presence in absence, and you can learn a lot about togetherness in separateness. In some ways, I think that the whole project of fiction is that you’re asking somebody to leave themselves and be somebody else in this fictive space.

It’s weird that you point this out, because I don’t think I had made that connection yet, which is sort of terrifying. But in a good way! I think it’s good to be terrified, especially when you’re thinking about your work. I think work should come from an agitated place, from a need to express something, or a kind of terror of something being lost.

Thinking back to each of these different stories that you just referenced, I was in such different places in my life. “Certain American States,” the title story, is the oldest thing in that book. It wasn’t originally the title story. It wasn’t even going to be in the book, but it eventually came back as a story that I had written not knowing that it was a precursor to a lot of other things. I don’t know what it is about leaving. I think about identity shedding a lot.

Could you say more about why you think about shedding identity?

This is why I think I think about it, which is probably not the real reason I think about it. I grew up in a pretty religious environment in Mississippi and spent almost all my time in church as a kid, and I read the Bible, and I was really concerned with living my life correctly on those terms. And, also, with finding more in the Bible than maybe other people had noticed. For instance, I got to the part in the Old Testament where you’re not supposed to eat anything with a split hoof and I was like, Wait a second, my family is eating bacon all the time. I told them, We’re not supposed to be eating this, according to the Bible. And my mom sort of introduced the idea of the Bible not being maybe something that we were interpreting straightforwardly. But I was like, Well, I’m not risking it. So, I basically went kosher when I was twelve, not knowing that’s what I was doing.

But then eventually I read other things, I started learning about other religions, and I moved out of Mississippi—only to Tennessee, but it was a big thing because I went to a school with a bunch of people from different backgrounds. My first roommate was Hindu. The world was suddenly so much bigger than I thought it was and I had a total crisis. I stopped going to church and had identity and ideological confusion. Eventually I read a lot more about Eastern philosophy and Zen and many, many years went by, and then eventually the ideas that seemed the most true to me—and that eventually were a balm for the existential trauma of being raised believing in heaven and hell in a visceral way—were concepts in Zen Buddhism: the idea that there’s something in everybody that’s not them. I think there’s this part in everyone that doesn’t know your history, doesn’t deal with any of the things that happen to you or the things that you think you’re supposed to do or look like. And so, if there’s that thing, then any other thing can be on top of it. So even if you think you’re very antisocial, you can be really outgoing. There’s no personality trait that’s actually inherent to a person.

Or this is just what I feel in some certain moments when I’m not encumbered with my identity. So, I think I’ve traced it back to that. Right now I’m working on a book that’s dealing even more with multiplicity of identities and the kind of papier-mâché quality of identity not being an important thing but sort of this costume that we pass through at different moments in order to tell a story. When I go through periods where I meditate a lot, I find it hard to engage with fiction because, I don’t know, it’s just harder to get there. I’m still interested in the costume of this world and I don’t want to go off into the woods and separate myself, but then how do you hold those two ideas at the same time? Because I can’t really leave this idea behind anymore, especially because for me it’s so essential to staving off the fear of God and hell, you know? I don’t think you ever get away from it if you have that first childhood impression of heaven-hell, good-bad, are you doing it correctly, when you die is this thing going to happen? It’s hard to get away from that logic.

Wow. So, your current so project is about identity, you said, but that’s not the one that’s coming out this summer, which also is about identity?

Pew, which is coming out this summer, has a person in the center of it that doesn’t have an identity. Not because they don’t claim one…I don’t even exactly know how to talk about what they are because everybody sees something different when they see this person. Some people see a woman, some people see a man, some people see younger, older, different races, or whatever. But nobody agrees and so there’s this kind of tiptoeing around. Like, What do we do with this person that doesn’t have one of these things that we use to communicate with each other? And, of course, it’s completely impossible and doesn’t exist and is sort of surreal in that way. But at the same time, that is how we are—we are all that sort of person. At our core we don’t have any of that stuff that we think we have. I believe that anyway. But the new one I’m working on is more playful. There’s something sort of austere about Pew and that’s just how it had to be, but this other one has a person at the center who wants to have more fun with the costume of identity and sort of shift through a bunch of them.

Pew, which is coming out this summer, has a person in the center of it that doesn’t have an identity. Not because they don’t claim one…I don’t even exactly know how to talk about what they are because everybody sees something different when they see this person. Some people see a woman, some people see a man, some people see younger, older, different races, or whatever. But nobody agrees and so there’s this kind of tiptoeing around. Like, What do we do with this person that doesn’t have one of these things that we use to communicate with each other? And, of course, it’s completely impossible and doesn’t exist and is sort of surreal in that way. But at the same time, that is how we are—we are all that sort of person. At our core we don’t have any of that stuff that we think we have. I believe that anyway. But the new one I’m working on is more playful. There’s something sort of austere about Pew and that’s just how it had to be, but this other one has a person at the center who wants to have more fun with the costume of identity and sort of shift through a bunch of them.

In your lecture today you talked about the issue of posture and rhythm and voice in sentences, and in an interview in the Paris Review you said that you think about body and posture a lot when you’re writing, that you think people are largely dissociated from their bodies. I think of the voice as a product of mind, although obviously it’s also embodied, in the sense that I’m breathing out and using vocal cords to speak right now. I’m wondering if you could talk about how sentences connect to or reflect this disjuncture. When people are dissociated from their bodies, how does the sentence reflect that?

If you are dissociated from your body and you’re writing from that place, there’s nothing inherently wrong with that. It’s just that the mind is a part of the body and there’s really no separation. They’re constantly in conversation with each other. I think that the kind of dangerous trick of fiction that fiction plays on the writer is that writing is going to associate you. Because it is a physical act. And so even if you’re not conscious of what’s happening in your body, I think it will come out in your syntax and your language, whether you want it to or not. There are some writers whose work has a cadence or something, you can feel their body a little bit more, and there’s some where it’s a little bit more muted. But I think it’s always still there. I also think there’s nothing wrong with dissociating from your body. There are all sorts of reasons why some people adapt to have dissociative behaviors. It’s self-protective. I think if I walked around being aware of everything that was happening with my body at all times it would be unbearable, you know? Our brain actually protects us from too much knowledge.

I like the idea that the writing associates the mind and body.

Yeah, you don’t get away with anything.

Your story “Violations” begins with a sentence that is a page and half long, and very, very long sentences show up in a lot of other places in your work, too. Could you talk about how you think about sentences and what should go in them? As discursive units, if that makes sense—stories versus paragraphs versus sentences?

Well, some sentences are just badly behaved. I think a lot of the decisions that happen when you’re writing a piece of fiction happen in creating rules and breaking them. There are so many writers that I really admire that work in ways that seem totally the opposite of mine. Fleur Jaeggy is a good example. Most of the books that I’ve read by her use these very discreet sentences. They’re very uptight. That’s not really a place that I usually write from. The voices that I’ve felt the most at ease in are a little sloppy, a little bit like a bag with everything in it, and they’re taking up too much space in the café, and they’re confused, and their hair is messed up. That’s the sort of mode that I like to move towards.

Photo Credit: Willy Somma

But then I can admire what she’s doing so much, maybe even more than writers that I might share more qualities with, in the same way that sometimes you like somebody who is so different from you. Like when you meet that person that has the same birthday as you, who grew up where you’re from, and you’re like, I hate you, you’re too much like me. I don’t know. The long sentence is only a long sentence depending on the other sentences that are around it. And there’s something really exciting about the kind of rollercoaster that one syntactical unit can have. But sometimes I find myself doing that, and I’m like, These are actually discrete sentences that shouldn’t belong together. I don’t actually know what my logic is for deciding, No, chop it back up, this is not a long sentence time, this is a time for a more traditional progression of ideas. I don’t think there is a moment where I’m like, Oh, this is a long sentence versus This is a paragraph that you just punctuated badly. And I know that there’s a line, I know there must be. I’ve mushed things back together and I’ve taken things apart at different times. I wish I had a better way to explain it other than I just follow some kind of weird intuition about it.

Maybe having to do with that voice question?

Yes! I do think that the longer I spend writing a story the more embedded the logic of that voice or character is, and then it can happen a little faster. Which is why I feel like what happens when I’m working on a book is that it takes years, and I’m writing the whole time. The same amount of words are coming out, but the words that happen for the first year and a half at least…maybe none of them actually get used, because I’m trying to teach myself this new instrument. I mean, it’s not wasted, it’s just like you’re learning how to play the piano, and these are not the songs you’re going to play in front of other people. Eventually you get to that. The more time I spend with the voice, the easier it is to know if I’m using it correctly or not.

I’m going to steal a question you asked somebody else once in an interview. Do you have a poetics of the sentence, and do you have any banned words or methods that you rely upon during the revision process?

I did ask somebody this. This is a tough question. I think it’s the correct thing to do, when you’re interviewing somebody to go look at what they’ve asked someone else and throw them one of their own because it’s interview karma.

I think it varies over time. I’ve noticed that I keep on doing this thing lately of including the word “somewhat” or “somehow” and then crossing out all these somehows and somewhats. I’m like, What do you mean “somewhat”? What are you trying to say there? I think there’s a part of me that’s extremely dramatic. In addition to church, I grew up in community theater, and I’m prone to these exaggerations and sometimes overdoing things. Every time I read “Because You Have To,” I notice that there’s one sentence in there that has too many clauses. It’s true, there’s just too many clauses, and I couldn’t see it while I was writing it, or while I was going through the million passes of a book that you have to go through before you’re done.

Poetics of a sentence…There are phrases that are very special, and you know one when you get it down, because it describes something that usually needs a lot of words to describe it. It uses something really tangible and immediate and you don’t need a complicated word, but it’s like it should be a word, it’s like it probably is a word in German or something. And when you get one of those, I think you have to give it space. So not everything can be as ornate as you might want it to be. Not everything can be beautiful. You have to have some space in the sentences that are boring, that are kind of fields, you know, that give the other things room. Because if you stack too many things together that are well-written, you just overwhelm the reader and they don’t want to keep dealing with you because you’re just too much. Not even too much as in too dramatic; it’s just they can’t see what’s good about you, because you’re trying to give them everything that you do. Like if you have somebody over for dinner and you’re like, I’m going to make you seventeen dishes of everything that I’m good at making and none of these things go together. You have to curate.

In the lecture you gave today you talked about starting sections with contrasts. Could you say more about that?

I think most writers dwell on opening sentences. We’re obsessed with a good opening. But I think every paragraph actually needs a good opening, though not a first sentence of a novel kind of thing. I feel like too much is made of the first sentence of a novel. It can be a lot more banal than some writers want or think it should be. But the opening of any section of any chapter and also the closing of any section or any each chapter has to have something a little bit unusual or stirring. That’s where you want to make sure those special things go, because that’s where they can be seen more clearly. It’s like you’re hanging your best painting in the spot with the most light. Somebody told me that once, and it’s one of the best pieces of advice I’ve heard. When I’m revising, it’s like, Oh, this needs to be rearranged to refocus attention on this thing. It’s the same as a first impression and last impression. The first thing you say to somebody when you meet them, or in any individual interaction, people remember that. And they remember the last thing. So, if you end you end a relationship by breaking somebody’s windows, they’re not going to remember the years of you being nice to them. They’re going to remember you breaking their windows. Every relationship contains conflict, but I think if you always make sure that you’re leaving things in a good place, then you can avoid burning bridges. And the same is true of chapters. You don’t want to end a chapter on something where it’s clear you’re just trying to end the chapter. You still have to shape the way that the reader exits any section so they’ll come back.

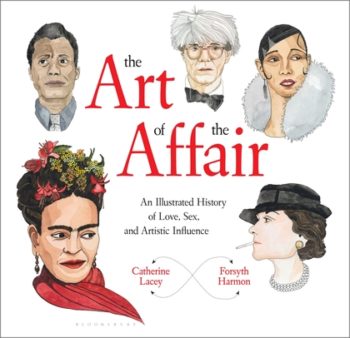

I was looking through your illustrated book on artistic influences, The Art of the Affair, last night. One thing that I was expecting before I actually saw the book was to see pairs of people or maybe trios, but you and your illustrator set it up so there’s an ongoing chain throughout, which I really loved. Are there writers or other artists who you think have influenced the way you write?

The dangerous thing about influences is that actually everything influences you. Your relationships influence you, the weather, anything you watch, every conversation you have. I think it all goes into this soup. Sometimes I really think I know who is influencing me, and it’s only later that I realize I was wrong. I read two Thomas Bernhard novels in short succession around 2008 and thought, Oh, wow what a weird guy. I remember being stirred by them and thinking he was a special, bizarre dude, but I didn’t think, Oh, I want to do this. But then I think his voice was so powerful to me that it got under my skin and even though I hadn’t read him for years, he ended up being a primary influence on my first book. It was The Loser and Woodcutters that I read, but pretty much all of his books are kind of on a continuum. I didn’t realize it until maybe a year after the book was out. I was like, Oh, God, that was the bug in my head, giving me a scaffolding for the voice that I didn’t know where it was coming from. It was Thomas Bernhard. And I wouldn’t have chosen him.

The dangerous thing about influences is that actually everything influences you. Your relationships influence you, the weather, anything you watch, every conversation you have. I think it all goes into this soup. Sometimes I really think I know who is influencing me, and it’s only later that I realize I was wrong. I read two Thomas Bernhard novels in short succession around 2008 and thought, Oh, wow what a weird guy. I remember being stirred by them and thinking he was a special, bizarre dude, but I didn’t think, Oh, I want to do this. But then I think his voice was so powerful to me that it got under my skin and even though I hadn’t read him for years, he ended up being a primary influence on my first book. It was The Loser and Woodcutters that I read, but pretty much all of his books are kind of on a continuum. I didn’t realize it until maybe a year after the book was out. I was like, Oh, God, that was the bug in my head, giving me a scaffolding for the voice that I didn’t know where it was coming from. It was Thomas Bernhard. And I wouldn’t have chosen him.

Often, it’s not writers. I often play one song on repeat when I work, an hour just listening to this one cello piece. It’s usually not words. Like Animal Collective. I can play their entire discography straight through. And it’s like two days of writing. Colin Stetson’s another one, this saxophonist who plays saxophone, but it doesn’t sound like a saxophone when he plays it. I think those are my influences lately.

Is the current book you mentioned earlier going to be a novel?

Yeah. I mean, it might not be. I’m not done, so who knows?

It seems like you’re also still publishing short stories, too. Are you moving back and forth?

I have a story file, and sometimes I go in there but it’s just a wreck. You know, there’s two or three that are done and then there are fifteen that are like, What is this?

Do you turn to stories when you need a break from the novel? Or do you ever need a break from the novel?

I need a break from the novel. I would love to just work on stories for a while, but that’s what you say when you’ve just finished a draft of something. My friend Laura van den Berg is a novelist and short story writer, and she has described herself to me as being more at home in the short story. But I think this conversation only happened after she’s just finished writing a novel. There’s something about doing the opposite of what you’ve just done in one way or another when you finish. I think this is true in any medium. Like you just made this long, confusing, dense book that has many, many elements to it, and then you’re like, I just want to write something that has just one person and almost no other characters and make it as small as possible. Then, when you finish that, you’re like, I don’t like this being in one place, and now I’m going to have a book that’s set in twenty places. You’re always kind of responding to the previous thing.

So maybe we’ll see another short story collection from you?

I hope so. With Certain American States, even though I feel good about the individual stories that are in there, I think it fails to be a collection in some ways. I’m trying to think about collections differently this time. I only have about three new stories that I feel really confident in. It may be many, many years. It’s really hard to say what it is that makes a story collection work. Eventually I’ll figure it out, maybe.