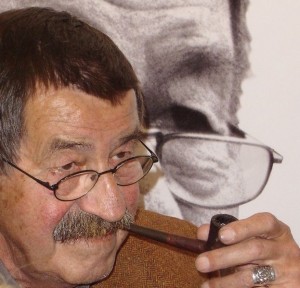

Nobel Laureate Günter Grass achieved international renown by spinning fantastical tales that reckon with some of the most grotesque events in human history. His second memoir, The Box, is another fantastical tale, though this one reckons with the detritus of his own life. Told using the fictionalized voices of his eight real grown children (from four different real women) and featuring another fictionalized real woman (photographer Maria Rama) and her imaginary magic camera, it pushes the boundaries of memoir. Or, perhaps more accurately, it blows up the form.

Nobel Laureate Günter Grass achieved international renown by spinning fantastical tales that reckon with some of the most grotesque events in human history. His second memoir, The Box, is another fantastical tale, though this one reckons with the detritus of his own life. Told using the fictionalized voices of his eight real grown children (from four different real women) and featuring another fictionalized real woman (photographer Maria Rama) and her imaginary magic camera, it pushes the boundaries of memoir. Or, perhaps more accurately, it blows up the form.

Grass opens with a seemingly straightforward scene – his eight grown children, gathered at his request around the kitchen table of his home near Lübeck. There’s a tape recorder, and the idea is for his children to talk about their father, who has just turned eighty. But things begin to shift and slide when the narrator, Grass, admits that his children will be using “words he has put into their mouths.” And few pages later, he introduces Maria and her magic camera, which “takes pictures of things that aren’t there.”

With these conceits, Grass ostensibly records his children’s version of his story over numerous recording sessions, each of which is a different chapter. These take place at different homes of Grass and his children, in assorted parts of Germany, with various permutations of his children present. The chapters are bookended with brief comments from Grass (rather, Grass writing the character Grass). The story is presented in vérité style, without quotation marks or any formal indication of who is saying what. It reads like an unedited oral history transcript.

Grass’ children, several of whom are well past middle age themselves, reminisce about their childhoods, meandering through their father’s post-war years, forming a composite of his life as he achieved literary superstardom in Germany and beyond. As his children recount, their childhoods weren’t particularly tragic or abusive; they were mostly dysfunctional, with lots of longing for their father’s interest and attention. As they grow up, some of the children are unaware of the existence of their half brothers and sisters. At one point, they recall Grass moving back in with his first wife, sharing a home with two of their children and his wife’s Romanian lover; they eventually divide the house like the nearby Berlin Wall. For the most part, Grass is absent, distracted, or otherwise engaged. “He wasn’t a play-father,” says one of his children.

Marie is introduced early on, nonchalantly, as the children pass around family photos at one of their recording sessions. She’s based on a real person – a family friend who was a photographer – and The Box is dedicated to her. As the children meander and reminisce their way through Grass’ post-war years, Marie and her magic camera are omnipresent and omniscient. She sees much of the confusion and turmoil firsthand, but her camera penetrates deeper. It produces prints that see the past, the future, alternate versions of the present, and the deepest wishes of its subjects. Its unique powers, along with Marie’s ubiquity, allow her to see the confusion and turmoil caused by Grass’ mental and physical restlessness. “My box is like the good lord: It sees all that was, that is, and that will be.”

As the children describe them, Marie’s photographs depict innocent fantasies, latent desires, melancholy wishes, and stark alternate realities. There are shots of Joggi, the dog, expertly navigating the Berlin U-Bahn. There are shots of Grass’ daughter Lara and her friends, naked, walking the Kudamm in Berlin. There are shots of a family trip to Brittany that depict the children as young soldiers wearing steel helmets and gas masks among the ruined, long-abandoned battlements, looking not unlike Grass did during the war.

Marie has a different relationship with Grass, and the prints from her magic camera often supply the raw materials for his writing, especially his work after debut novel and international sensation The Tin Drum (1959). The children remember the Stone Age pictures the camera produced that formed the basis of Grass’ 1977 novel The Flounder. They recall it supplying research for The Meeting at Telgte (1979), set during the 30 Years War.

Marie has a different relationship with Grass, and the prints from her magic camera often supply the raw materials for his writing, especially his work after debut novel and international sensation The Tin Drum (1959). The children remember the Stone Age pictures the camera produced that formed the basis of Grass’ 1977 novel The Flounder. They recall it supplying research for The Meeting at Telgte (1979), set during the 30 Years War.

For Telgte, Grass takes the pictures himself, shooting a concrete parking lot. “Because, he said, in this very spot a good three hundred years ago stood the Brückenhof, which will be the scene of the action.” The prints depict outbuildings and barns with thatched roofs, portrait photos of historical figures at the real Telgte meeting. “He wanted the box to help him rewind,” one of Grass’ children says. “Historical snapshots,” says another.

Günter Grass is obsessed with the past and has spent a lifetime attempting to come to terms with it. There’s a German word for this: Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which literally translated means “managing the past,” and usually refers specifically to the Holocaust. This fuels his compulsion to write. It’s the desire to understand the role his friends, his family, his fellow citizens – and Grass himself – played in this crime. It’s the desire to make a new German society. This isn’t unique to Grass – many post-Nazi German writers fall into this category – but he is easily the most famous.

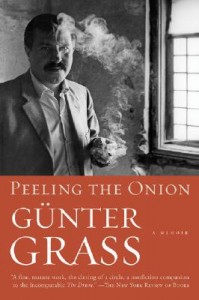

The Box was preceded by Peeling the Onion (2006), which offered a linear – though lyrical – account of his childhood, war years, and early literary success. In it, Grass revealed that he was drafted into the Waffen SS and saw limited action in a tank unit at the end of the Second World War. Long a critic of ex-Nazi participation in German politics, and perhaps the leading cultural voice calling for Germany’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the book prompted a firestorm of controversy that tainted Grass’ reputation. Mild critics called him a hypocrite, while others called for the Nobel laureate to return his prize. Grass kept his prize and continued to work.

The Box was preceded by Peeling the Onion (2006), which offered a linear – though lyrical – account of his childhood, war years, and early literary success. In it, Grass revealed that he was drafted into the Waffen SS and saw limited action in a tank unit at the end of the Second World War. Long a critic of ex-Nazi participation in German politics, and perhaps the leading cultural voice calling for Germany’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the book prompted a firestorm of controversy that tainted Grass’ reputation. Mild critics called him a hypocrite, while others called for the Nobel laureate to return his prize. Grass kept his prize and continued to work.

Peeling the Onion is what one might call a typical memoir. There are times when you think Grass might be spinning a yarn: Was the Joseph he met in a POW camp, the Joseph who Grass said sounded like a “grand inquisitor” and quoted Saint Augustine when he beat him at dice, was this really Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict? Still, in relation to other memoirs, it’s not off the charts. In fact, as a reader, you’re always waiting for Grass to…well, be Grass. But he earns and keeps your trust. Perhaps he chose strategy this because of the book’s dynamite revelations. If you’ve positioned yourself as the moral compass of post-war Germany, and you’re going to disclose that you were part of the Waffen SS, Marie and her magic camera aren’t going to help you. This was one case where Grass wasn’t going to play around with the past.

I had a hard time with The Box, and it’s for the same reasons that I’ve had a hard time with Grass in general. I don’t always trust him. I feel like he’s pulling one over on me, crossing the literary fourth wall from time to time to beat me over the head with my ignorance, my failure to pick up on symbols obvious to anyone who’s read Grimmelshausen, the complete works of Schiller, or Heidegger’s Being and Time.

In The Box, I first thought that Grass was being diabolical, using Marie as an elaborate joke that his children play on him as they reminisce, telling him a tall tale as revenge for him making a career of it. One of the children says: “It’s possible even we, sitting here and talking, are just figments of his imagination – what do you think?” Of course, this is Grass writing in his children’s voice, so this is actually true.

Grass – well, the character of Grass – adds fuel to the fire in one of the chapter bookends, cryptically stating: “Yes, children, I know: being a father is only an assertion, one that has to be constantly corroborated. That is why, to make you believe me, I must lie.”

But Grass is also a writer who once said, “If I say potato, I mean potato.” It’s hard to take him seriously on this point, given his oeuvre is peppered with talking animals; a child who wills himself to stop growing and possesses the superpower-like ability to use his voice as a weapon; and the aforementioned magic camera.

But permit me to twist the phrase a bit: “If I say talking dog, I mean talking dog.” “If I say self-created little person with super powers, I mean self-created little person with super powers.” “If I say magic camera, I mean magic camera.”

Maybe there’s something to this. Let’s apply it to The Tin Drum, Grass’ first novel. He claimed that the only way he would really convey the story of the rise of Nazism and its wake of destruction was to do it from the point of view as a child; this necessitated one that never aged, had the faculties of an adult, and while a little crazy and unreliable, provided an utterly unique perspective.

Maybe there’s something to this. Let’s apply it to The Tin Drum, Grass’ first novel. He claimed that the only way he would really convey the story of the rise of Nazism and its wake of destruction was to do it from the point of view as a child; this necessitated one that never aged, had the faculties of an adult, and while a little crazy and unreliable, provided an utterly unique perspective.

Marie’s camera is a device that allows Grass to explore the issues of past, present, and future that have always confounded him. Think of it this way: Grass was largely an absent father, but here he is writing about Marie and her nearly omniscient knowledge of his children. He must know something about his children to write a character who knows nearly all this is to know about them:

But you, Nanette, she managed to capture with her box even when I could not be with you, but in my thoughts was right there, holding your little hand that completely disappeared into mine. Mariechen knew our wishes, after all. That made it possible for me to be near you when you had dropped your house key or your pocket money again. I helped you look; it was a long way between home and school. Cold, I would say, warm, warmer, warmer, hot … And sometimes more turn up than had been lost. The pleasure we both took in found objects.

So, the father knows his children after all. The Box is how Grass sees his children (via Marie and her magic camera, Grass’ creation) and it’s Grass imagining how his kids see him (via Grass writing in their voices). He’s a fair and often critical assessor of his behaviors and their impact. The children try to work out what drives him, and it’s clear early on that they’re aware of his preternatural drive, one that’s more powerful than any other force in his life: the pursuit of truth, the reconciliation of past, present, and future. “That’s just how he is. Always was. I have to work through it, he said.”

In the end, I came to believe just about everything in The Box except for Marie’s magic camera. I suppose I could attempt to corroborate the real biographies of his eight children with those that are recounted here. But those are the details that he had no need to make up. As for the magic camera, it’s incidental as well. The point of The Box, at least to me, is that the octogenarian Grass needs to believe that despite all of the family turmoil he’s caused, that his children understand that he was compelled by a greater power – namely, the quest for truth. By writing in a realistic way (despite the magic camera) how his children could come to this understanding and acceptance about their father, perhaps he’s really giving them a blueprint to follow in real life. Or, at the very least, he’s making his case.

According to The Box, Grass’s children, by and large, turned out fine. Professionally, they are successful. Personally, they seem happy. Their childhoods were, like other childhoods, bittersweet, though certainly more tumultuous than most. The world is richer for Grass’ work, but there was a cost. The Box is tragic in this respect, because for a man obsessed with making sense of the past, he now has to account for his own, and there’s more than a tinge of regret. It’s not an apology to his children – as far as Grass is concerned, there’s nothing to apologize for – but it does offer an explanation: Sure, I could have been around more, but the time we spent, wasn’t it magical?