There is a moment during a perfectly paced, perfectly executed meal when everything transcends. The diners look up from their plates —wine-drugged, conversation-lulled—and gaze at each other in wonder. Reality has shifted, and everything is beautifully, impossibly suspended.

There is a moment during a perfectly paced, perfectly executed meal when everything transcends. The diners look up from their plates —wine-drugged, conversation-lulled—and gaze at each other in wonder. Reality has shifted, and everything is beautifully, impossibly suspended.

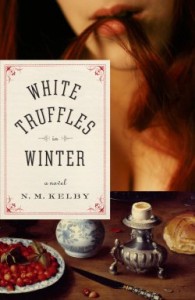

N.M. Kelby’s White Truffles in Winter (W.W. Norton) is the literary equivalent of that moment.

A fictional exploration of the life of acclaimed French chef Auguste Escoffier, Kelby’s latest novel is served in courses. We begin with the young Escoffier’s seduction of his new wife, the poet Delphine Daffis, at a kitchen table in Cannes. We encounter his famous friends, patrons, and lovers (most notably the mercurially divine Sarah Bernhardt) as his culinary star rises. We journey into the famed kitchens of the Savoy and the Ritz, where Escoffier revolutionized fine dining. And we linger with champagne ghosts at Escoffier’s retirement villa in Monte Carlo, unsure of whether we’ll ever be ready to end the meal.

There’s no doubt the food writing here is first-rate. In the pages of Escoffier’s imagined memoir, we learn how to humanely drown langoustines in Moët, the proper way to serve cherries jubilee to a queen (hint: never with ice cream), and why naming a sausage after Jesus is generally good for business. But the real story is not, as the fictional Escoffier suggests, “A Memoir in Meals,” but rather a memoir in women.

There’s no doubt the food writing here is first-rate. In the pages of Escoffier’s imagined memoir, we learn how to humanely drown langoustines in Moët, the proper way to serve cherries jubilee to a queen (hint: never with ice cream), and why naming a sausage after Jesus is generally good for business. But the real story is not, as the fictional Escoffier suggests, “A Memoir in Meals,” but rather a memoir in women.

On her deathbed, Delphine asks Escoffier to do the one thing he has been unable to do throughout his long life: create a dish in her honor. To inspire (or perhaps ignite) his creativity, she asks Sabine, their household cook, to wheel her into the kitchen, where she oversees a dish that is perfection in its simplicity. Escoffier’s reaction encapsulates their marriage:

“The eggs are your doing?”

“They are my gift to you.”

“You should be in bed.”

“I should be immortal.”

And perhaps she should. But immortality – and Escoffier’s love – comes far more easily to Bernhardt. Their first love scene is one of the strongest and most creative moments in the book, and without giving anything away, establishes white truffle oil as Escoffier’s lifeblood.

So powerful is Bernhardt’s presence in Escoffier’s life that she seems to reincarnate multiple times—first as renegade cook Rosa Lewis, and later as Sabine. He creates countless dishes in her honor, despite the fact that she rarely eats. And when he encounters a rare white truffle, found out of season in winter, he protects it like a secret until he’s able to bestow it upon the dying Bernhardt. It is a lovely moment, made all the more poetic when it crumbles from age, inedible.

So powerful is Bernhardt’s presence in Escoffier’s life that she seems to reincarnate multiple times—first as renegade cook Rosa Lewis, and later as Sabine. He creates countless dishes in her honor, despite the fact that she rarely eats. And when he encounters a rare white truffle, found out of season in winter, he protects it like a secret until he’s able to bestow it upon the dying Bernhardt. It is a lovely moment, made all the more poetic when it crumbles from age, inedible.

But if Bernhardt is his muse, Delphine is certainly his home. Despite living apart for thirty years, Escoffier eventually returns to her, and to their family home in Monte Carlo. Throughout their separation, he romances her though letters and gifts sent from a fictional “Mr. Boots” (actually Bernhardt’s jealous name for Lewis), and at the end, it is Delphine’s culinary spirit that he evokes in the final pages of his memoir, with an artist’s approach to mashed potatoes:

This is a difficult dish; do not allow the seemingly simple ingredients to deceive you…[e]very choice you make, every step you alter, affects your ability to change the ordinary into the extraordinary. You must be brave. You cannot falter. This is a dish of quiet miracles. You must believe in them.

Too often, fictionalized history reads like a forgettable meal. In White Truffles in Winter, Kelby has instead given us the quiet miracle.

Further Links & Resources

- Read the first several chapters of White Truffles in Winter on the W. W. Norton website.

- Visit Kelby’s website – nmkelby.com – for tour dates, information about her other books, and an audio excerpt of her reading from the new novel.