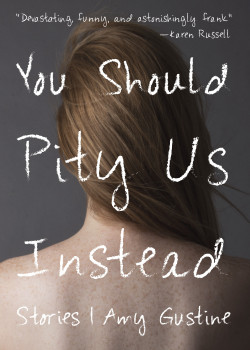

Perhaps what I love most about Amy Gustine’s story “All the Sons of Cain” (which can be found now in the May/June 2015 issue of Kenyon Review, and next February in Gustine’s collection, You Should Pity Us Instead, forthcoming from Sarabande Books) is the way it embeds a mother’s personal quest to find her missing son in the political context that shapes her dangerous journey. When the story opens, an Israeli woman introduced only as “R’s mother”—the only identity that matters to her—is hiding in her apartment, avoiding the crowds who protest daily on the street below. Her son, a soldier captured by Hamas, has become a shifting political symbol, and the rapidity of these shifts are captured nicely in the cadence of Gustine’s prose:

Sometimes they use him to protest another prisoner trade, sometimes to support it; sometimes to urge settlements, other times to condemn those already built; to push for a two-state solution or to warn against it. Once they were protesting a tax, another time something to do with toilets. . . Reconciliation and revenge. Hostages and prisoners. Murderers and soldiers. It all sounds the same from up here.

Another thing I love about this story is that it reads like a thriller. When Hamas releases a video in which R claims to have converted to Islam, his mother decides to take his rescue into her own hands. She sneaks into Gaza through Egypt, bringing a handful of photos, and begs strangers to help her locate him. Her travels and their accompanying risks are recounted in hair-raising detail as she bribes people to get what she needs, never knowing whether they’ll keep their promises, and is finally taken to a tunnel that leads from a kitchen in Egypt to a child’s bedroom in Gaza. Once in Gaza, she confronts the hardships of trying to stay in hiding without shelter:

The first night she sleeps behind a dumpster, and the next morning her bones feel as if they’ve been hammered. . . The next night she sleeps on the beach hidden behind a pile of cinder-blocks, and in the morning her bones feel only gently pinged, like the keys of a piano too strenuously played.

Aid comes in the form of a thirteen-year-old boy, who leads her home to his own mother, who reluctantly allows her to stay. This boy becomes a kind of second son to R’s mother, as she discovers on a day when she fears he, too, will be taken away:

When he gets home hours later, she realizes she’s been preparing all day to surrender in exchange for his long nose, his too-big teeth. The puff of hair in the back of his head that bounces when he runs.

Mothers accumulate in this story, for yet another mother is hiding in this house in Gaza: a young girl who has run away from home to give birth out of wedlock, escaping brothers who hope to kill her. While the focus remains on R’s mother and her quest, we see how a plight that seems unique when the story opens—how many mothers set out to rescue their sons from foreign militants?—lies on a continuum of vulnerability for women living in nations at war.

Children, in contrast, disperse, traded to other mothers or other countries for survival. The girl who is hiding from her brothers will leave her child with the woman who has sheltered her and R’s mother, while R’s mother will pretend to be the girl’s aunt help her escape to Egypt. R himself, we learn, has been rescued once by his mother already: he is not her biological child, but an orphan she found in Istanbul after an earthquake. Not surprisingly, she has not been able to locate him in Gaza. He will remain there, and she can only hope that his conversion to a new religious identity—whether thrust upon him, or chosen as an adaptation to the regime that holds him now—will keep him safe.

Children, in contrast, disperse, traded to other mothers or other countries for survival. The girl who is hiding from her brothers will leave her child with the woman who has sheltered her and R’s mother, while R’s mother will pretend to be the girl’s aunt help her escape to Egypt. R himself, we learn, has been rescued once by his mother already: he is not her biological child, but an orphan she found in Istanbul after an earthquake. Not surprisingly, she has not been able to locate him in Gaza. He will remain there, and she can only hope that his conversion to a new religious identity—whether thrust upon him, or chosen as an adaptation to the regime that holds him now—will keep him safe.